Front Range Earth Architecture: Why and Why Not?, written by Michael Shernick, is a paper that looks at the history and viability of earth architecture on Colorado’s Front Range. Click here to download the paper in PDF format.

Kashgar: The End of a Mud Brick City

An old way of life is coming to a crashing end in north-western China with two-thirds of Kashgar’s Old City being bulldozed over the past few weeks under a government plan to “modernise” the area. Nine hundred families already have been moved from Kashgar’s Old City, “the best-preserved example of a traditional Islamic city to be found anywhere in central Asia,” as the architect and historian George Michell wrote in the 2008 book “Kashgar: Oasis City on China’s Old Silk Road.” Over the next few years, city officials say, they will demolish at least 85 percent of this warren of picturesque, if run-down homes and shops. Many of its 13,000 families, Muslims from a Turkic ethnic group called the Uighurs (pronounced WEE-gurs), will be moved.

Israel Siege on Gaza Leads to Mud Brick House

Building earthen structures like bread ovens and small animal pens is a technique many Palestinians are familiar with, but extending the method to houses isn’t a notion that has taken hold in Gaza. But Jihad el-Shaar, who lived with his wife and four daughters with extended family wanted to build a home of their own. After waiting for two years, it was apparent that the siege would make cement unavailable so he decided to build his house of mud.

The Adobe Alliance Featured in Mother Earth News

Photo by Yasmina Rossi.

“The allure of elegant earthen architecture can be life-changing. At least that was the case for urbane New Yorker Simone Swan, who in the 1970s became fascinated with the ideas and designs of renowned Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy. Then the 40-something executive head of the Houston-based Menil Foundation, Swan moved to Cairo to study with Fathy. She became his most passionate advocate, and transplanted his adobe building techniques to the Southwestern United States.”

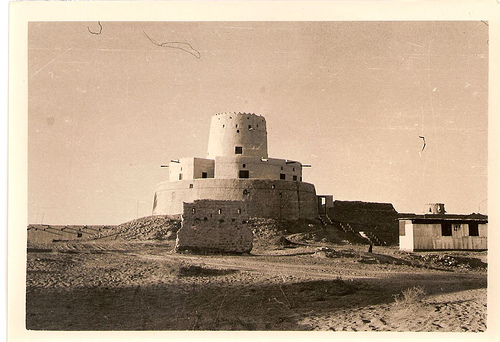

Jahili Fort in Al Ain Abu Dhabi

Historically, the daily life of the inhabitants of Al Ain, today the second largest city in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, took place in the palm gardens of the oasis and the surrounding settlements and markets. To protect the oases, watchtowers and forts were erected. The Jahili Fort located in the modern-day centre of the city is the largest of Al Ain’s forts. Built in the 19th century by Sheikh Zayed the First, it can be seen from the Al Ain oasis to the west of the city. With its distinct three-tiered profile, the fort is now a national monument, pictured on the 50 Dirham note and often used as a logo or model for new architecture. The old fort was erected at the end of the 19th century.

The fort was recently restored by Roswag & Jankowski Architekten, Berlin.

The interior surfaces remain true to the historical appearance. The ceiling consists of palm rafters and palm leaves. A local clay plaster has been used for the interior wall surfaces. In the exhibition areas a grey coloured fine clay finishing plaster made by Claytec was used to create a neutral background for the exhibition spaces. The floors likewise follow historical precedence and are made of rammed earth stabilised with a wax to cope with greater wear and tear.

All new insertions such as doors and furniture, made of corian or wood composite, are coloured white differentiating them from the surrounding building. The external render of the existing walls was examined and repaired where necessary. Previous renovation works had employed a non-traditional plaster with added gypsum for the crenelations. This plaster is too rigid and already exhibited defects; it was replaced with a clay plaster. The building was then given an overall finishing coat of clay plaster. The earth plaster is maintained at regular intervals as is traditional with this historical material. When used as an external render, clay plaster should be regarded as a weathering surface that needs ongoing maintenance, typically every two years, sometimes after sustained periods of heavy rain. Sandstorms are also a cause of erosion.

Most of the spaces will house a permanent exhibition “Mubarak bin London: Wilfried Thesiger and the Freedom of the Desert” showing photographs taken in the 1940s by the researcher and explorer Wilfried Thesiger who in the 1940s crossed the deserts of the Arabian peninsula repeatedly travelling with Bedouins and documenting what he saw with a Leica camera.

The 90 cm thick external earth walls offer excellent thermal insulation. The additional insulation on the roof improves still further the indoor room temperature and together with the solar protection windows on the façade provide effective protection against the extreme heat outdoors. The building is kept at a constant 24°C using a water-based cooling system integrated into the plaster layer of the walls. This minimizes the need for additional air cooling so that only fresh air is required. The cool indoor temperature of the walls and the reduced need for cold air makes the indoor climate more comfortable and reduces the energy consumption. An actual room temperature of 24°C equates to a felt room temperature of 22°C. The plant and technical installations for the entire fort are located below ground in the buffer zone.

The construction is made of traditionally available building materials including earth, palm products and to a lesser degree also timber. The quartered palm trunks can span a room of about 2.70 m and dictate the strongly partitioned structure of the historic buildings. The walls consist of air-dried earth blocks which can be built directly on the sandy ground without the need for foundations. A matting made of palm fronds covered with earth is laid on rafters made of split and quartered palm trunks arranged at an incline. The small amount of timber available was used for the door and window frames.

Abari Adobe Dome

Abari, a socially and environmentally committed research,design and construction firm that examines, encourages, and celebrates the vernacular architectural tradition of Nepal. In this recent project, the dome will be covered with bamboo roof as a protection again heavy tropical rain. The adobe structure is reinforced with bamboo to make it earthquake resitant. This structure is a reception of community structure, which is also being built.

Mud and the Automobile

A curious relationship between mud brick architecture,clay and the automobile exists in two very important earthen architecture building cultures: among the Ndebele people of South Africa, whose vividly painted mud brick houses have been transposed to the automobile, and in northern New Mexico where the descendants of the Indigenous Pueblo people and Spanish colonists created a unique style of mud brick architecture from which emerged the invention of the lowrider.

Ndebele

The Ndebele people of South Africa are famous for the the colorful patterns applied to the exterior of their houses, which are made of a mixture of dung, mud, and clay. Their distinctive house-painting style, originally based on a similar but less colourful style originally developed by the Northern Sotho or Pedi, flowered and achieved its creative pinnacle within the almost slave-like conditions which the Ndebele endured on the white-owned farms of the south-eastern Transvaal during the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century.

The almost exclusively female creators of these arts have for decades been borrowing elements from the social and cultural repertoires both of their neighbours and of modern industrial society. Peter Rich writes, “The strength of Ndebele spatial models and aesthetic grammar allowed them to invest images reinterpreted from other cultures, with their own symbolic meaning. They had an affinity with the stylised art deco that was prevalent in cities such as Pretoria in the 1940s and ’50s. The changing trends in Western society, notably the American car culture of the ’50s, fashion and infatuation with images of power/electricity/jet aeroplanes, were other catalysts. ‘We see what we want to see and make it our own’, proclaims a Ndebele matriarch.”

Application of paint to earthen wall

Because of the striking designs adorning the houses, tourists drove great distances to see the Ndebele, often from as far away as Johanasburg, which was 100 miles away. According to Elizabeth Ann Schneider, the Ndebele women noticed the license plates on the cars and although they could not read them, they liked the shapes of the letters and numbers and began to paint them on their earthen walls. They mirrored the shapes of these forms to create symmetrical patterns on the front of their houses. Wavy designs known as “tire tracks” are still sometimes applied to walls and also appear on floors.

Modern “BMW” Ndebele House

‘Mural decoration is the prerogative of the woman; it denotes her unique and intimate relationship with the indlu (home) and her passive response to being exploited socially and politically,’ wrote Margaret Courtney-Clarke in Ndebele, but with the pressures of a modern era, the Ndebele women became increasingly dependent upon the automobile to find work in cities that were a good distance from their villages. This cultural shift led to the application of Ndebele motifs, which until then used the car as inspiration, to the car itself.

Car decorated with Ndebele paintings in Pretoria, South africa.

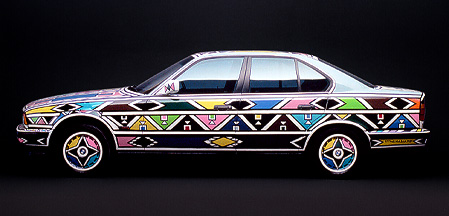

Many Ndebele women became well known for their craft and the most celebrated of these artists is Esther Nikwambi Mahlangu. Born in Middleburg in 1936, she was invited in 1989 to exhibit at the Pompidou Art Museum in Paris. In 1991, she was invited to paint a prototype of the new BMW 525i model. Esther’s car, eleventh in the Art Car Collection, was the first to be decorated by a woman artist and as a black woman artist from a little-known South African community to be included in a prestigious international artistic line-up of artists including Frank Stella, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol and David Hockney made this fact all the more exceptional.

Esther Mahlangu’s Ndebele BMW

In 2008 Mahlangu was invited to paint another car—this time the new Fiat 500.

Mahlangu next to her Fiat 500

Today, calling attention to the automobile’s long relationship with the the architecture of the Ndebele, an old car, painted in this evolving tradition, joins a sign announcing the entrance to the famous mud brick village of Lesedi.

Sign at the entrance to the village of Lesedi.

New Mexico

Mud brick was the principal building material Northern New Mexico from the founding of the first European colony in 1598 until the mid 20th century, and hand formed mud had been used in to construct multi-story dwellings for thousands of years prior. Industrialization, mining and the lure of jobs in cities transformed what was largely agrarian society in New Mexico into a society increasingly dependent upon the automobile to travel the great distances from the isolated villages to cities and the mines in central Colorado.

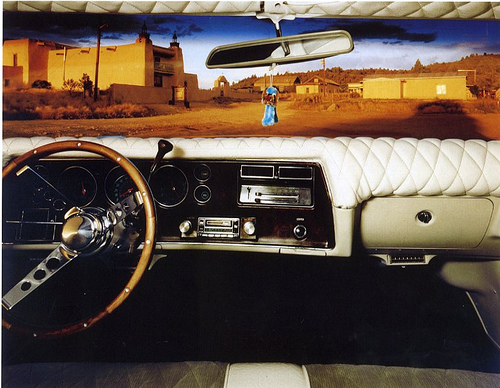

The San José de Gracia Church, built between 1760 and 1776 and considered a model of the adobe architecture found throughout New Mexico. Here the church can be seen through the windshield of Levi Lobato’s 1972 Chevrolet Monte Carlo.

From the desire to bring with them a piece of home from a landscape in which the people were deeply rooted, emerged the lowrider—a chapel on wheels that evoked the essence of the ancient baroque mud brick churches that were at the center of village life.

Dave’s Dream as displayed in the Smithsonian Museum’s former Road Transportation hall, with photomural of the El Santuario de Chimayo, and an assembly of trophies won by this lowrider automobile. Photo by Jeff Tinsley, Negative #: 95-3340

The altar of El Santuario de Chimayo whose color scheme and ornamentation could be seen as influential to “Dave’s Dream”

The long lines of automobiles produced in the 40’s, 50’s, 60’s and 70’s were reminicent of the long corrieras—adobe houses that were composed of several branches of a single family constructed through a series continuous additions as the family grew. The interiors and/or exteriors of the car were often lavishly ornamented, reminiscent of the baroque ornamentation found in the mud brick interiors.

Ruin of a corriera house in San Idelfono, New Mexico and a 1963 Impela.

Low-rider Cadillac named “Chimayo,” Chimayo, New Mexico, 1997 by Craig Varjabedian

Today, the mud brick village of Chimayo, New Mexico is considered the spiritual center of the lowrider world and nearby Española, New Mexico is considered the lowrider capital of the world. Today lowrider culture has become a global phenomena, but the ornate vehicles and over-zealous use of hydraulics that tilts the automobiles into torqued positions still recall the leaning ancient mud brick structures of northern New Mexico.

And while lowriding has become a serious artform and mud brick architecture has roots in the sacred, the combination of adobe architecture and the automobile has also been poked fun at in popular culture as evidenced by the adobe car, featured in a Saturday Night Live “fake commercial“, a transcript of which appears below:

Spokesman: These days, everyone’s talking about the Hyundai, and the Yugo. Both nice cars, if you’ve got $3,000 or $4,000 to throw around. But, for those of us whose name doesn’t happen to be Rockefeller, finally there’s some good news – a car with a sticker price of $179. That’s right, $179. The name of the car?

Adobe. The sassy new Mexican import that’s made out of clay. German engineering and Mexican know-how helped create the first car to break the $200 barrier. At this price, you might not expect more than reliable transportation – but, brother, you get it! Extra features: like the custom contour seats, or the beverage-gripping dash. And the money you save isn’t exactly small change!

Jingle:

“Hey, hey, we’re Adobe!

The little car that’s made out of clay!

We’re gonna save you some money

that you can spend in some other way!

Hey, hey, we’re Adobe!

Hey, hey, we’re Adobe!

Adobe!”

Spokesman: Adobe. You can buy a cheaper car. But I wouldn’t recommend it!

Announcer: Not approved for street use in some states. No warranty either expressed or implied. All sales final.

Interestingly, most major automobile manufacturers actually employ clay to visualize their designs before they go into production. This art of designing cars in clay has existed since the 1920’s, just as the Industrial Revolution was beginning to influence the culture of the remote villages of Northern New Mexico and still today, most of the futuristic prototypes found at car shows are clay models crafted with multiple axis computer controlled mills that carve the car from clay based on designs created using 3D modeling software.

High Speed CNC Machine

And as sophisticated machinery is being developed to shape the automobiles of the future out of clay, cumbersome vehicles exist that move across flat terrains, which consume mud and excrete large quantities of mud brick to fuel a growing demand for adobe houses in New Mexico and beyond. Such machinery can be found at The Adobe Factory in Alcalde, New Mexico and can produce 20,000 mud bricks per day.

An adobe machine

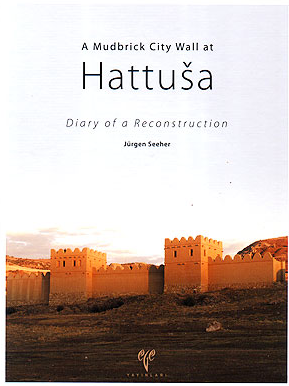

A Mudbrick City Wall at Hattuša

Situated in Central Anatolia, Hattuša remained the capital city of the Hittites from 1650/1600 to around 1200 BC. Here, as recently as 2003 to 2005, the German Archaeological Institute has rebuilt one stretch of the mudbrick city wall. The scope of this project in experimental archaeology has been to recreate a part of the wall using the same materials the Hittites had at hand when they built their original walls so long ago. Each step necessary for the construction was fully documented so as to enable us to assess not only the amount of building materials required but also the manpower and time the Hittites must have invested in the various tasks of construction.

This volume presents the results gleaned from this documentation. From the production of the first mudbrick to the dedication of the finished structure, each and every undertaking has been described in detail and is presented here accompanied by 573 illustrations.

For more information visit:

German Institute of Archaeology (In english, german and turkish)

Hattuscha-webpage (in English, German and Turkish)

This book is published also in German and Turkish:

Die Lehmziegel-Stadtmauer von Hattusa

Bericht über eine Rekonstruktion

ISBN 978-975-807-194-7

Hattusa Kerpic Kent Suru

Bir Rekonstrüksiyon Çal??mas?

ISBN 978-975-807-193-9

The Jahili Fort

The Jahili Fort built in 1898 in Al Ain is now at the centre of an exciting conservation, restoration and development project that will preserve the values of this historic building whilst transforming the site into an active visitor destination.

Bousillage Construction

The Gaudet House c. 1830, Lutcher, Louisiana

Bousillage, or bouzillage, a hybrid mud brick/cob/wattle and daub technique is a mixture of clay and Spanish moss or clay and grass that is used as a plaster to fill the spaces between structural framing and particularly found in French Vernacular architecture of Louisiana of the early 1700s. A series of wood bars (barreaux), set between the posts, helped to hold the plaster in place. Bousillage, molded into bricks, was also used as infilling between posts; then called briquette-entre-poteaux. The bousillage formed a solid mud wall that was plastered and then painted. The bousillage also formed a very effective insulation.

French Acadienne house in Lyon, France

The tradition was brought to New Orleans from France by the Acadienne (Cajun). The technique also has Naive American influences. This paper describes how “When the French built in Louisiana, their earliest houses (maison) were of this frame structure, but with the post in the ground (poteaux en terre). Sometimes the post were placed close together palisade fashion (cabane). This was a technique used by local Indians. The Indians infilled the cracks between the posts with a mixture of mud and retted Spanish moss. The French did likewise and called this mixture “bousillage”. The first framed structures were covered with horizontal cypress boards (madriers). The roof (couverture) frame was finished with cypress bark, shakes, boards, or palmetto thatch. All of these earliest structures had dirt floors and were usually only one room deep and two rooms wide separated by a fireplace.”