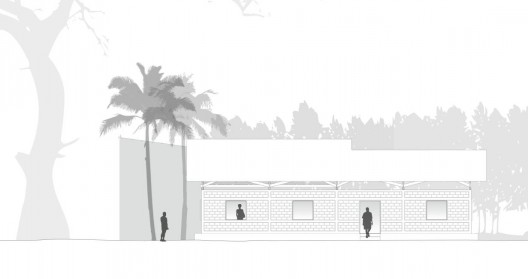

Revealing the Potential of Compressed Earth Blocks—A Study in the Materiality of Compressed Earth Blocks (CEB): Lightness, Tactility, and Formability, by Egyptian architect Omar Rabie, documents explorations of the potential of CEB while studying at MIT, The Architectural Association and Auroville.

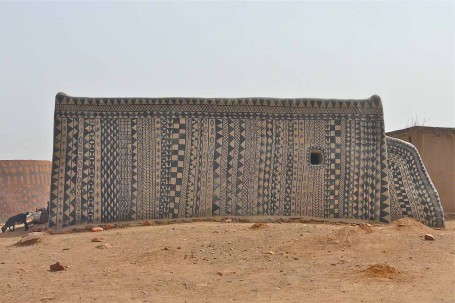

In these two experimental mock-ups, Rabie explored the different possibilities of bondings using one block—specifically how the shape of the single block influences the block bonding patterns in a stack bond and running bond.

This portion of a wall was built of specially formed interlocking blocks to increase friction to test how high friction masonry wall will highly resist lateral loads in comparison to walls constructed with standard blocks. In this case, the blocks are interlocked in the long direction of the wall. This experiment proved that it is possible to freely form more complex CEBs and build walls with an unusual bonds, like this strong zigzag bond.