The #1 Thing you need to know about the next 40 years, according to the Smithsonian is: “Sophisticated Buildings Will Be Made Of Mud”

Ant Earth Architecture Uncovered

A giant ant colony is pumped full of concrete, then excavated to reveal the complexity of its inner structure.

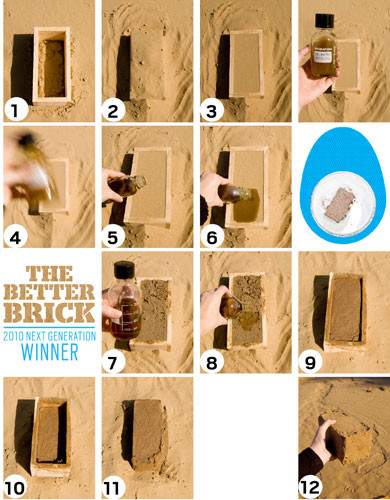

Bio-Engineered Sand Brick

The winner of the 2010 Metropolis Next Generation Design Competition proposes a radical alternative to the common brick: don’t bake the brick; grow it. In a lab at the American University of Sharjah, in the United Arab Emirates, Ginger Krieg Dosier, an assistant architecture professor, sprouts building blocks from sand, common bacteria, calcium chloride, and urea (yes, the stuff in your pee). The process, known as microbial-induced calcite precipitation, or MICP, uses the microbes on sand to bind the grains together like glue with a chain of chemical reactions. The resulting mass resembles sandstone but, depending on how it’s made, can reproduce the strength of fired-clay brick or even marble. If Dosier’s biomanufactured masonry replaced each new brick on the planet, it would reduce carbon-dioxide emissions by at least 800 million tons a year. “We’re running out of all of our energy sources,” she said in March in a phone interview from the United Arab Emirates. “Four hundred trees are burned to make 25,000 bricks. It’s a consumption issue, and honestly, it’s starting to scare me.” Read more…

Ma Terre Première Pour Construire Demain

Ma Terre Première Pour Construire Demain is an exhibition on earth raw as a building material as it pertains to environmental, economic and aesthetic of today and tomorrow. The first exhibition of this magnitude on the subject, Ma Terre Première Pour Construire Demain reveals the full potential of this granular material found in geology, physics, architecture and art. The exhibition was produced in collaboration with the research laboratory of the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Grenoble, CRATerre. Ma Terre Première Pour Construire Demain is co-produced with four regional agencies as the host in turn until 2013: The Flying Strasbourg, the Science Forum Villeneuve d’Ascq, the Pont du Gard and Confluence Museum in Lyon.

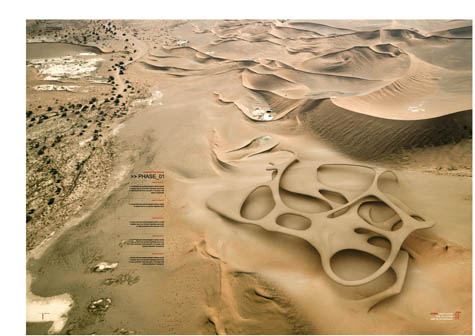

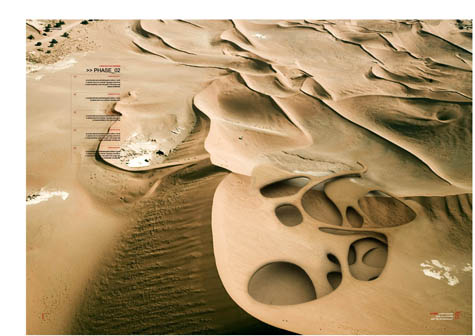

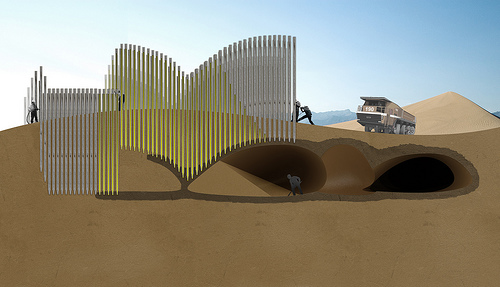

Dune Anti-Desertification Architecture

Dune Anti-Desertification Architecture investigates adaptive (as opposed to mitigatory) strategies leading to the creation of a climate-conscious

architecture that responds to the extreme environments of tomorrow’s globally-warmed world. Highly speculative yet buildable, the scheme aims to find innovative solutions to combat desertification in the Sahel region of Africa, where sand dunes are currently moving southward at a breathtaking

pace of around 600m per year, ruining the land and making it impossible for the inhabitants of this area to make a living or even stay in their homes. The forced migration of desertification refugees is perhaps more threatening in Nigeria than anywhere else. With a population of over 140 million people, Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa, with serious desertification issues throughout its northern states. It was Nigeria’s former president, Olusegun Obasanjo, who initiated the anti-desertification Green Wall Sahara initiative in 2005. This pan-African scheme seeks to plant a shelterbelt across the continent, from Mauritania in the west to Djibouti in the east, in an attempt to stop the dunes from migrating. The trees are being planted right now.

An architectural response to this campaign would be to go beyond the mere planting of a mitigatory shelterbelt. Habitable spaces can be created in close proximity to the trees. By cutting through the sand dunes and digging down to find water and shade, an artificial oasis can be formed underground.

The sand is solidified using bacillus pasteurii, a microorganism with which professor Jason DeJong has turned sand into sandstone in a mere 1,400 minutes. This technology of organically cementing networks of sand dunes into habitable barriers that stop the desert from spreading has never been proposed before, but on hearing about this project, the professor was enthusiastic: “I do think the application you are talking about is possible”. I’m proposing anti-desertifi cation structures made out of the desert itself, sand-stopping devices made of sand: a poetic proposal that simultaneously works in a sustainable way with local materials and assets.

Special emphasis has been put on finding a solution that is high-tech in result but low-tech in application and construction, with the economical scenario being hard to pin down as this method is virgin territory. It is recognized that poor people are highly vulnerable to the effects of weather, as drought can cause famine while good rains can cause drops in crop prices. The architecture presented here could form a stable base from which to fight back against both effects.

Read more [ BLDGBLOG | Holcim Foundation ]

Sandcastles Hold Key to Rammed Earth Strength

The secret of a successful sandcastle could aid the revival of an ancient eco-friendly building technique, according to research led by Durham University. Researchers, led by experts at Durham’s School of Engineering, have carried out a study into the strength of rammed earth, which is growing in popularity as a sustainable building method.