Location: Aknaibich, Morroco

Completion: 2014

Project Area: 55 m²

Budget: 25.000€

Architect(s): BC architects & studies + MAMOTH

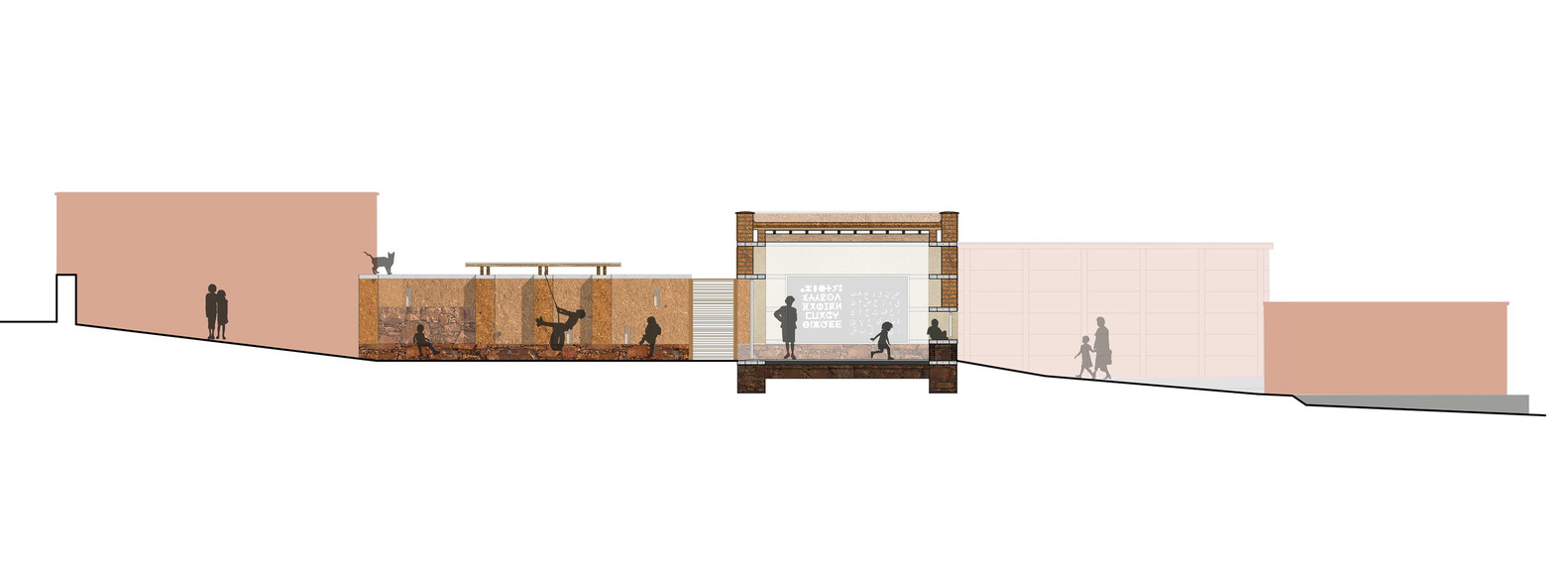

The population of Aknaibich collapsed from 1266 inhabitants in 2014 to only 634 in 2013. Of which the majority were young students migrating to the center of Agadir 30km away, to study. This rural-urban trend exacerbates not only the physically abandonment of Aknaibich but the cultural abandonment of traditional earthen building. Returning migrants opt for the faster and easier concrete construction to build their village homes, scattering the village with exposed rebar.

BC Architects proposes a strategic combination of traditional vernacular seismically maximized by innovative technologies, built by the community, in an architecture that might be called a new, contemporary vernacular. The vernacular embraces the humanity of Aknaibich, it’s logical and thoughtful response to the communities needs. The utilization of local typologies and materials allows bioclimatic functioning. A dialogue is created with the existing concrete school on site, leaving it up to the teachers and children to make their own perceptions of the juxtaposing materiality. The school complex further visualized the importance of education in the small village.

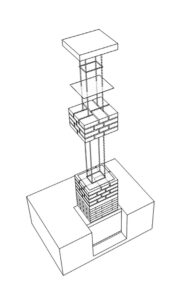

Adobe Brick + Qued Stone

Gravel earth, excavated from the site, and clayey soil, from the river bank of Qued Souss are made into sun-dried soil bricks. The process of forming the earth into a brick is only ever done in the village by a single craftsmen. Stones found at the same river bed are traditionally used for foundations, for its strength and durability. These stones are processed for an even wall surface.

Cement ‘Where it is Necessary’

To resolve seismic challenges of traditional earthen buildings, cement is strategically placed, in ring beams connected by reinforcement bars and the foundation, to guarantee stability. In replacement to local wood, which is poor in tension, normally used in Moroccan construction. At the south facade, these ring beams become small platforms or niches. At the north facade, the ring beams become openings to the interior courtyard.

Rammed Earth ‘Leh’

Rammed earth, ‘Leh’ in Berber, walls are using for enclosure walls.

‘Tamelass’ + ‘ Nouss-Nouss’

For protection against weather and impact, a rendering of straw, sand, and earth is used to finish exterior adobe walls. In interior spaces, a finer and more worked plaster, made of sieved clayey soil and gypsum called ‘Nouss-nouss,’ or half-half in Berber. The material reflects light well, luminating the classroom.

Ratan

Moroccan carpenters weave in between wooden beams in order to create a flat roof and a pergola. Overlaid on a lattice of wooden beams, the ratan allows for hot air to rise and escape the interior space. Then a thick, heavy earthen flat roof, additionally insulated by 10cm of cork, slows down the heating process from the exterior.

The interior courtyard consists of a playground as well, protected from the sun by a pergola covered by ratan. This outdoor space creates enough shade that it doubles as a possible outdoor classroom.

References

- Photograpy, Frank Stabel

- Issuu BC Portfolio

- BC Architects & Studies

- Arch Daily