Will Bruder is an American architect known for his innovative use of materials and site-specific designs. Born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1946, Bruder’s background spans art, sculpture, and architecture. He studied at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, earning a degree in Fine Arts, and later apprenticed under visionary architect Paolo Soleri, which significantly influenced his work in the desert Southwest.

Bruder’s work focuses on creating architecture that integrates with the natural environment, using innovative material choices and architectural forms. His approach prioritizes materials that connect the building to its surroundings, as seen in his use of adobe for the Matthews Residence.

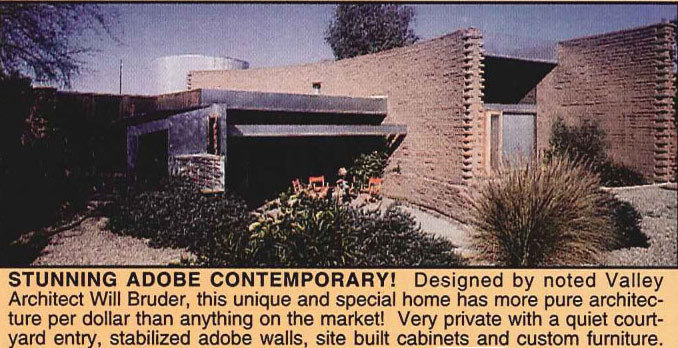

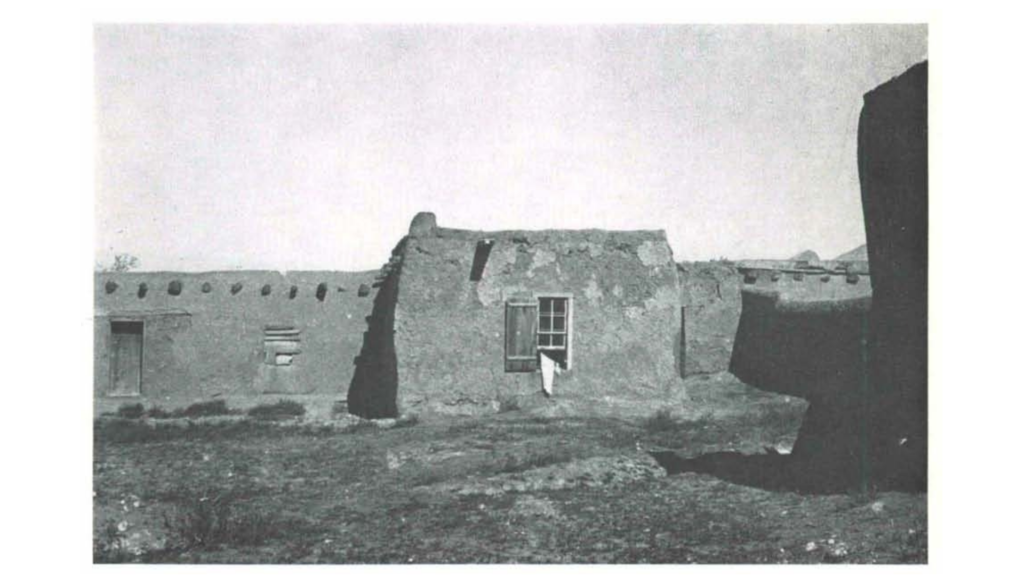

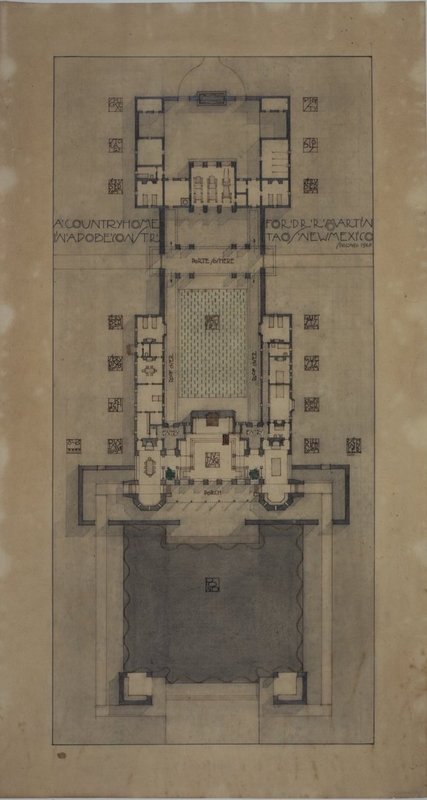

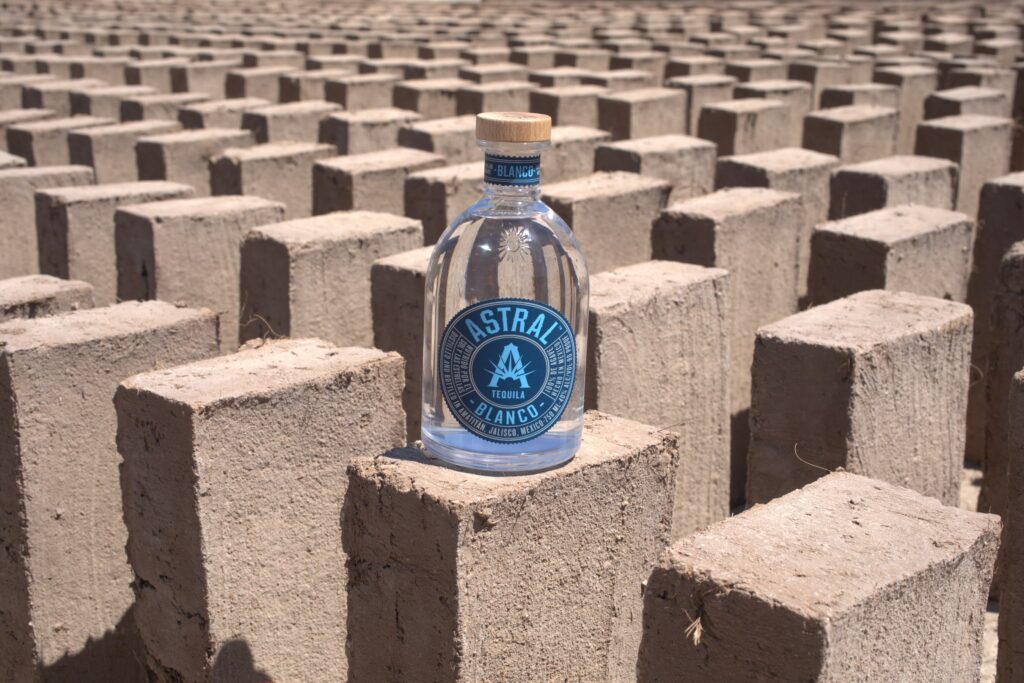

The Matthews Residence, designed by Will Bruder, was built between 1979 and 1980 and received the 1983 Environmental Excellence Award for its innovative design. The residence is a 2,800-square-foot adobe home. The primary material of this residence is adobe brick, a traditional earth material made from sun-dried bricks, which is able to blend into the natural landscape. Adobe also offers excellent thermal properties, helping regulate temperature in the desert climate.

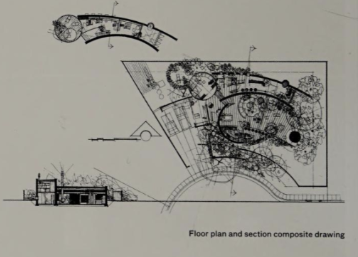

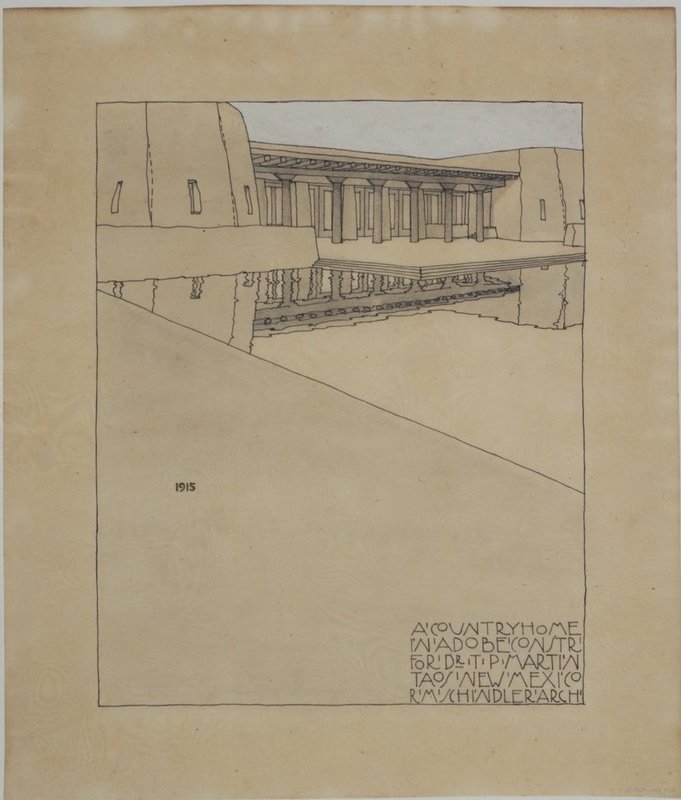

Inspired by the traditional Southwestern courtyard house, the design features curving adobe walls, strategically shaped to reduce exposure to the intense Arizona sun. The house spans a large double cul-de-sac lot in a suburban area of west Phoenix.

The layout creates a dynamic interplay between expansive and more intimate spaces, enhanced by the flowing geometry of its curves. The design’s sense of light, compression, and openness is carefully crafted, with a long skylight running from the entrance, introducing a play of light that highlights the contrast between rougher materials like adobe and concrete floors and the more refined details of oak and galvanized steel.

A key inspiring aspect is how Bruder masterfully combines adobe with modern materials like steel and wood, which creates a dynamic contrast between natural, traditional, and modern industrial materials. This combination enriches the architectural narrative by blending the old with the new. The combination of modern architectural design with natural, sustainable materials makes the Matthews Residence a source of inspiration for architects interested in sustainability and regionalism.

Interestingly, this is the only known Bruder house constructed from adobe, making it a rare and distinctive project. The way adobe is used in this design adds to its uniqueness, and it remains one of the most intriguing examples of Bruder’s residential work.

Matthews ResidenceCitations:

AZ Architecture. “Matthews Residence – Will Bruder Architect – Adobe.” AZ Architecture, https://azarchitecture.com/architecture-guide/matthews-residence-will-bruder-architect-adobe/. Accessed 23 September 2024.

USModernist. “Will Bruder.” USModernist, https://usmodernist.org/bruder.htm. Accessed 23 September 2024.

Rael, Ronald. Earth Architecture. Princeton Architectural Press, 2009, pp. 120-121.