A project by Yu-Shao Wu, Siyu Liang, and Rachel Sherr

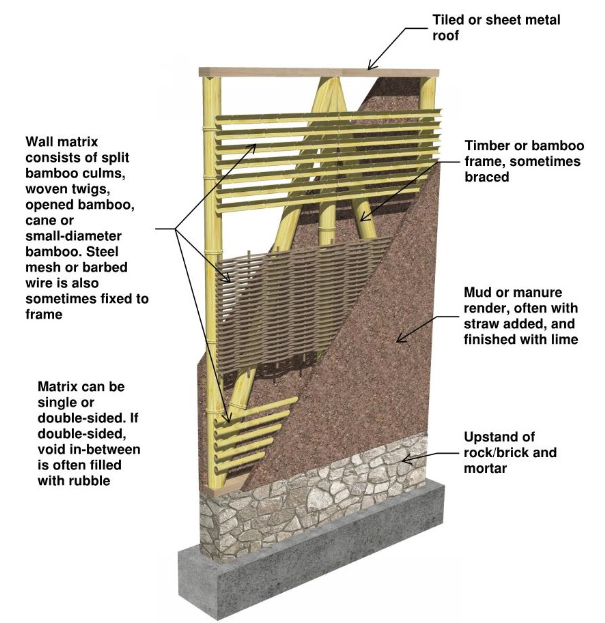

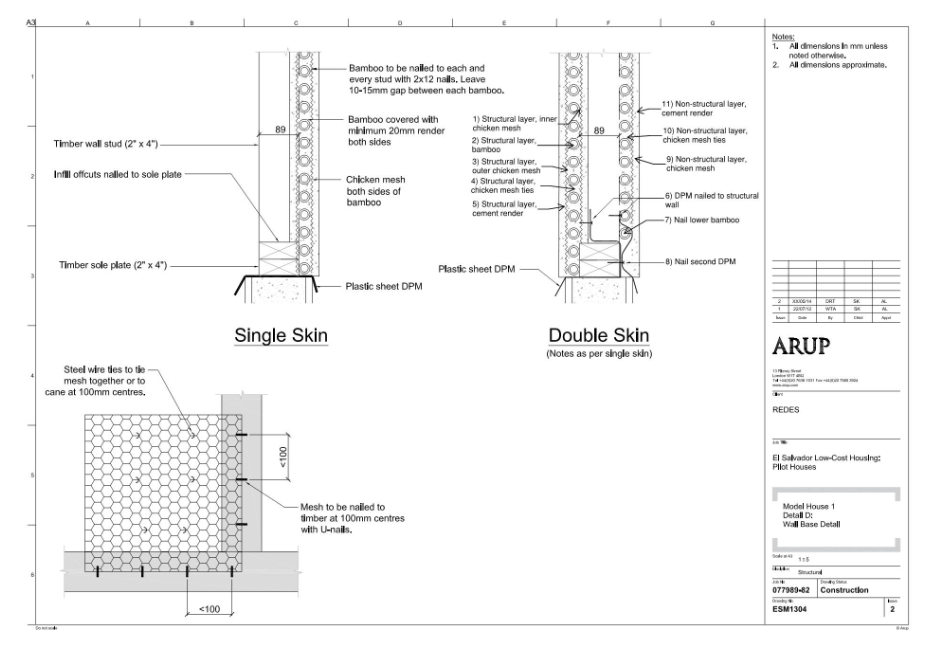

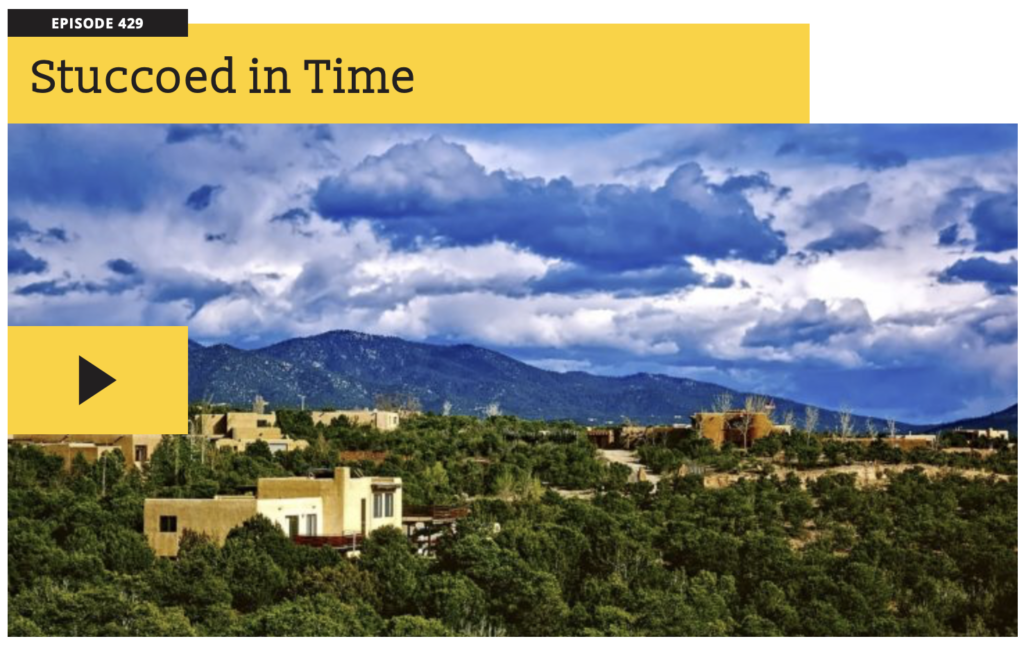

Rammed earth is an ancient technology for building with earth. Though some modern rammed earth structures rely on additions like cement to increase compressive strength, rammed earth can, with the correct soil content, form load-bearing walls.

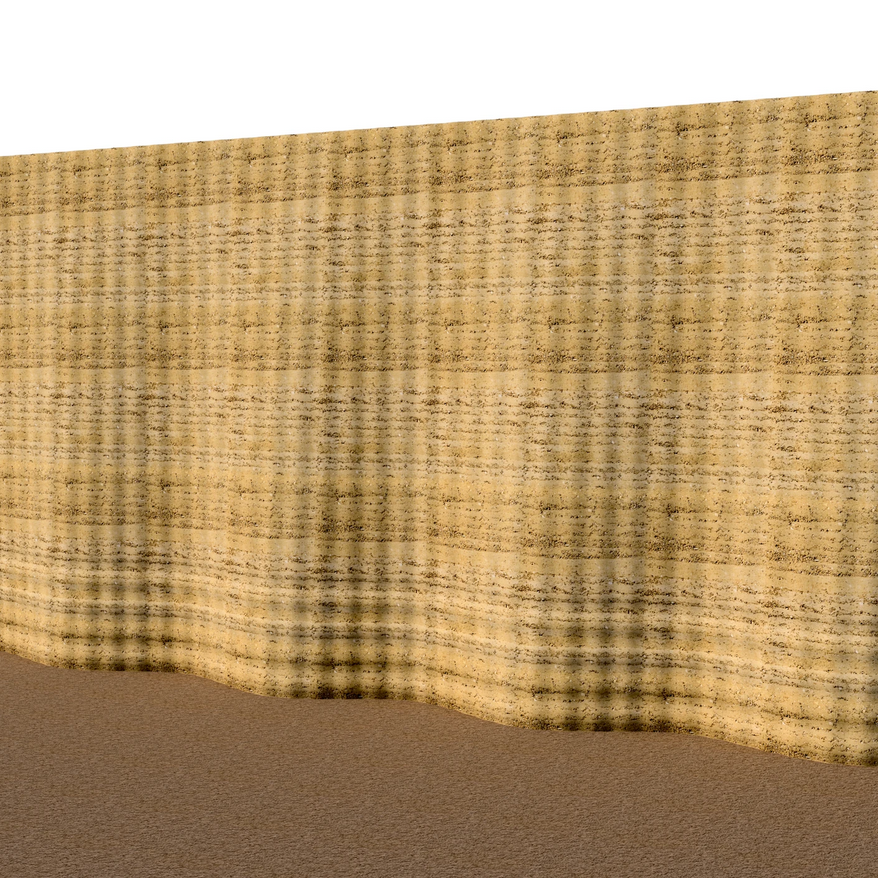

Traditionally, rammed earth is created using timber formwork. Perhaps the most common is a mobile formwork module that is moved along a wall, compacting a few feet of earth at a time. Each layer is compacted successively, sometimes with overlaps, which can increase the strength of the structure.

As earthen architecture moves into the digital realm, with 3D printing rigs capable of producing entire houses made of digital earth, rammed earth must follow. Rammed earth can be digital in two ways: 1. the earth is rammed via a digital process, and 2. the formwork for the rammed earth is created via a digital process.

Per current research on the subject, the first way of creating digital rammed earth is rare. It would require a high degree of sophistication in robotics and computer programming to create the automated processes required. The latter method is more common, and more achievable. This is also the method we settled on to experiment with digital rammed earth.

Inspired by a few precedents of various earthen architecture technologies, both digital earthen architecture and rammed earth, we created a new design. We incorporated elements from Anna Heringer’s METI school in Rudrapur, Bangladesh, and two projects by the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC), both realized using Crane WASP, a large scale 3D printer specifically designed to print earth. These two projects are TOVA, a small 3D printed dwelling, and a thesis project that embeds a staircase within a 3D printed earthen wall. Additionally, our digital formwork was inspired by the speculative renderings of earth artist/architect Scarlett Lee.

Our model explores the tectonic relationship between timber and rammed earth, particularly the horizontal members that penetrate the rammed earth wall as part of the formwork. We elected to leave these members embedded within the wall, and they serve as supports for the roof and staircase. In this way, we have maximized the structural role of the rammed earth wall, while also exploring innovative ways of incorporating digital strategies into this ancient technology.

References: