Wattle and daub is a traditional building technique that has been used in the UK for centuries, dating back to prehistoric times and continuing well into the 20th century. This method was particularly common in medieval timber-framed buildings and remains an important part of Britain’s architectural heritage.

Construction Method

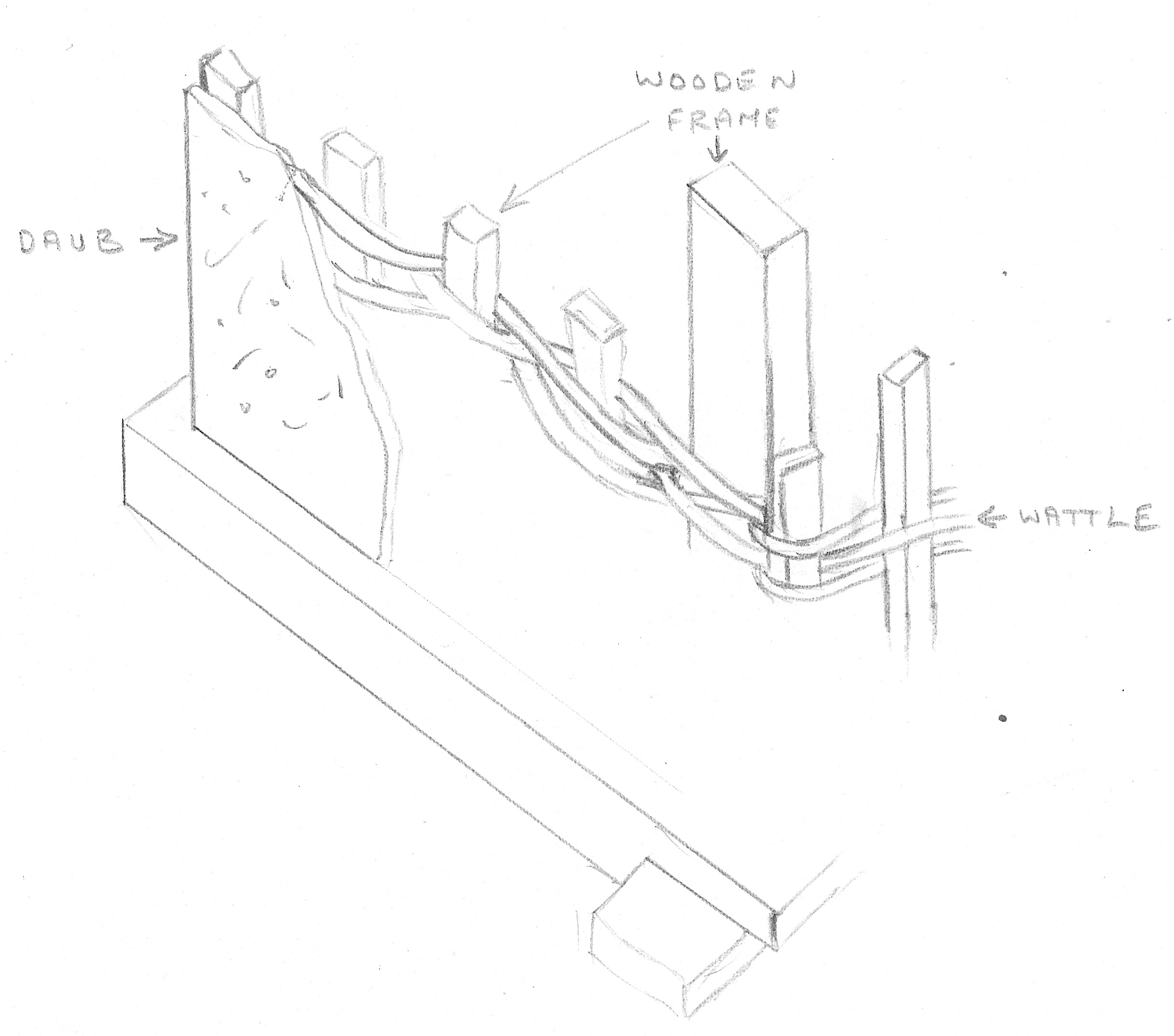

Wattle and daub consists of two main components:

- Wattle: A lattice of wooden strips or branches (often hazel) woven between upright poles. This forms the structural framework for the wall.

- Daub: A mixture of wet materials applied to the wattle. The daub typically consists of:

- Binders: Clay, lime, or chalk dust

- Aggregates: Earth, sand, or crushed stone

- Reinforcement: Straw, hair, or other fibrous materials

The daub is applied in stages, first as balls pressed into the wattle from both sides, then allowed to dry before being scratched and covered with a lime plaster. Finally, the wall is often whitewashed for additional protection.

Advantages

Wattle and daub offers several benefits:

- Strong yet flexible, accommodating structural movement

- Good insulation properties

- Effective moisture management

- Durable when properly maintained

Historical Significance

Archaeological evidence of wattle and daub has been found in various locations across the UK, often associated with medieval manors and other important sites. In England, remains of Iron Age circular dwellings constructed using this method have been discovered.

Conservation and Modern Use

Many historic buildings in the UK still feature original wattle and daub panels, some up to 700 years old. Conservation efforts focus on preserving these panels, with repairs carried out using traditional techniques. Some heritage organizations, like the Weald & Downland Living Museum, offer courses in wattle and daub construction and repair.

In recent years, there has been renewed interest in wattle and daub as a sustainable building method for new timber-framed structures, due to its use of local, natural materials and low environmental impact.

Wattle and daub remains an important part of the UK’s architectural heritage, showcasing traditional craftsmanship and sustainable building practices that continue to be relevant today.

Sources

- https://www.meldrethhistory.org.uk/buildings/building_materials/wall-and-framework-materials/wattle-and-daub

- https://www.wealddown.co.uk/museum-news/wattle-and-daub/

- https://www.buildingconservation.com/articles/wattleanddaub/wattleanddaub.htm

- https://www.britannica.com/technology/wattle-and-daub

- https://www.lowimpact.org/categories/wattle-daub