For centuries, Ukrainians have utilized the earth to create diverse and resilient dwellings. While wood played a role in certain regions, earthen construction techniques were widespread, particularly in the steppe and forest-steppe zones where wood was scarce. One of the most common methods was wattle and daub, employed as far back as the Neolithic Trypillian culture (5500-2750 BC). This involved creating a woven lattice of wood (“wattle”) and then applying a mud or clay mixture (“daub”) to form the walls. This technique, while simple, provided sturdy and well-insulated structures. While the actual structures haven’t survived, the archaeological evidence provides insights into their building techniques. Museums like the Museum of Folk Architecture and Way of Life of Central Dnieper Ukraine in Pereiaslav preserve examples of traditional building techniques, including earthen structures. The museum is part of Pereiaslav National Historical and Ethnographic Reserve. It was created in the 1960s and is the first open-air museum in Ukraine. The skansen (open-air) area on the picturesque Tatar Mount is divided into several sections: a pre-Soviet Ukrainian village of the Middle Cis-Dnipro Region, crafts and trades of a reformed Ukrainian village, windmills, and the earliest period section. Its total area of 25 hectares contains about 300 items, 122 of which are folk architecture monuments from the 17th to 19th centuries. They include 20 households with dwelling houses and outbuildings, presenting over 20,000 artifacts, such as works of folk craftsmen, lobar tools, household items, archaeological materials, documents, and photos.

Links:

Neolithic Trypillian culture, Museums like the Museum of Folk Architecture and Way of Life of Central Dnieper Ukraine in Pereiaslav, Pyana Hata restaurant, Ukrainian hata Wiki, Ukrainian hata, Mazanka, Museum of Folk Architecture and Folkways of Ukraine

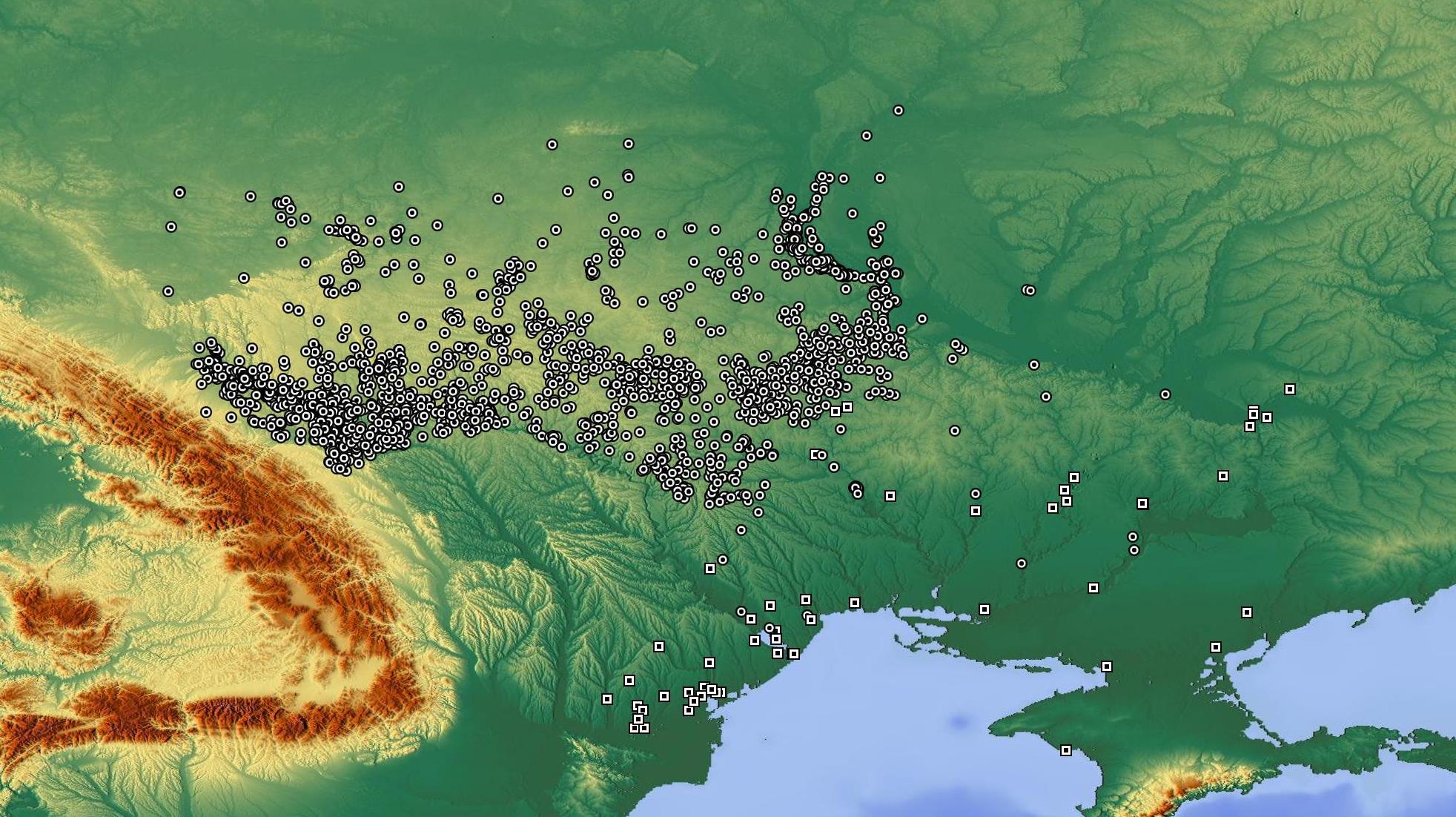

Neolithic Trypillan settlements, Southeastern Europe

1914

1914

Ukrainian traditional houses were generally built facing south to maximize sunlight for warmth. This often resulted in houses being positioned at various angles to the street, especially in hilly areas with complex terrain, creating a charmingly haphazard village layout. In flatter regions, houses were more likely to be aligned with the street.

In rural areas, the tradition of earthen construction continued to flourish, shaping vernacular architecture. Homes, outbuildings, and even churches featured cob walls made from a mix of clay, sand, and straw. This readily available material created thick, insulating walls that were well-suited to the Ukrainian climate.

Another prominent technique was the construction of mazanka houses. This type of house got the name mazanka from the word mazaty (Ukrainian: мазати; to smear, to grease, to plaster with clay mortar). These structures usually utilized a wooden frame filled with clay mixed with straw or reeds, brushwood, or woven willow branches. The walls were then plastered with a clay mixture and whitewashed, creating a distinctive and practical dwelling. The choice of technique often depended on the availability of local materials. They dominated areas with limited wood, clay, and straw, while regions with more forests might incorporate more timber framing. This adaptability is a hallmark of Ukrainian earthen building traditions, reflecting a harmonious/sustainable relationship between builders and their environment.

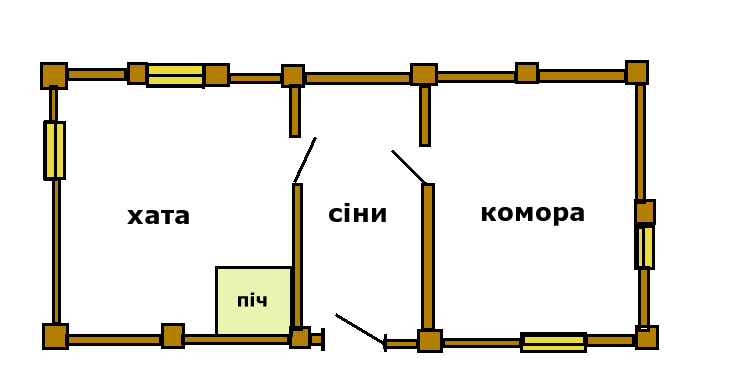

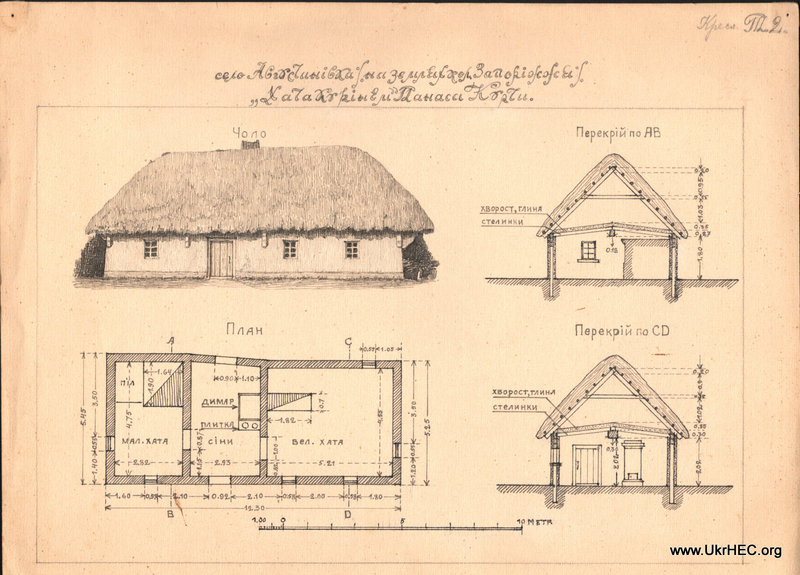

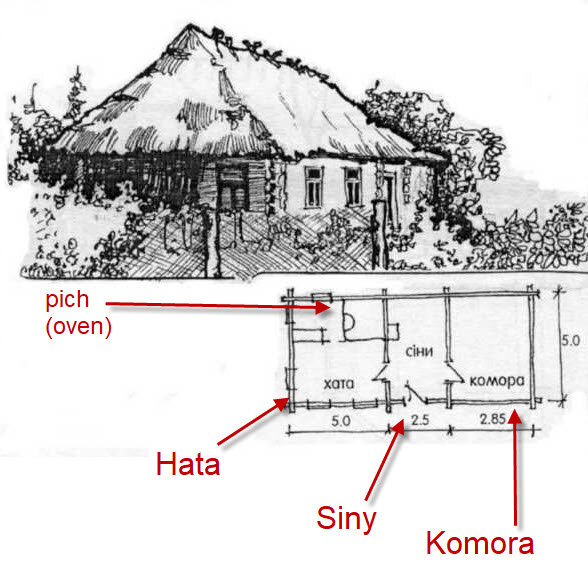

The architectural appearance of the folk dwelling – “khata” – and its internal organization in its main features are common throughout Ukraine. Khata is a rectangular, somewhat elongated building in plan, covered with a hipped roof; the ratio of the width of the building to the length ranges from 1:1.25 to 1:2.25.

The living space itself approaches a square – the most economical rectangular shape of a room, in which the perimeter of the walls and the cooling of the room are the smallest. A large entrance hall and a pantry attached to the living space lengthen the plan. If the hut is built for two independent living spaces with an entrance hall between them, then the building is stretched along the main facade and acquires an elongated shape.

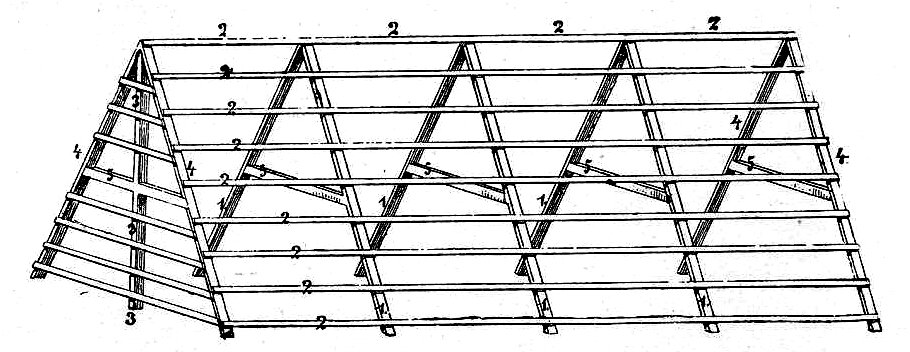

The most typical roof design in Ukraine was a hipped roof with four sides and sloping ends supported by rafters. These rafters were either attached to the top of the log walls or to longitudinal beams laid on top of the walls. In the Polissya region, a gable roof (two-sided) was also common, constructed in a few different ways: with a log covering, using supports shaped like chairs, or with posts supporting a main beam and the entire roof.

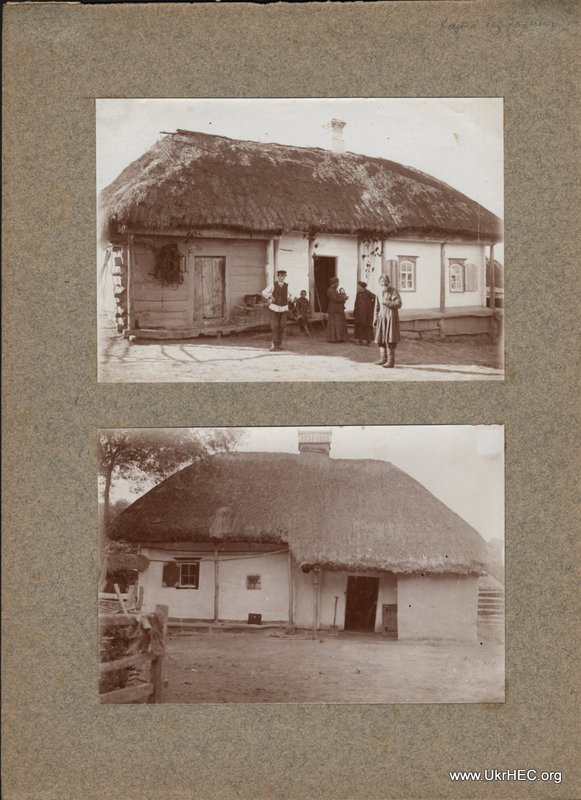

Roofs were typically covered with straw, either bound in sheaves or spread loosely. In forested and mountainous areas, the log structure of the house was left exposed, showcasing the craftsmanship of the interlocking logs. In the steppe and forest-steppe zones, houses were usually whitewashed inside and out, regardless of the building material, creating a striking contrast against the surrounding greenery. Colorful accents around windows, doors, and the base added a cheerful touch.

The simplest Ukrainian hut had two rooms: a large entrance hall used for storage and a warm living area. The stove dominated the living space, serving as a cooking area, storage space, drying rack, and even a bed! Kitchenware was kept near the entrance, while the sleeping area was located at the back, away from the windows.

The floor was made of earth in the early periods and later also had a special clay base. Only in some regions of Ukraine was the floor made of wood.

These time-tested techniques, passed down through generations, not only provided shelter but also shaped the unique character of Ukrainian villages. The whitewashed walls of mazanka houses, nestled among gardens and fields, created a picturesque landscape that continues to define the rural Ukrainian identity. Though modern materials have become more prevalent, the legacy of earthen construction remains an important part of Ukraine’s architectural heritage.

These time-tested techniques, passed down through generations, not only provided shelter but also shaped the unique character of Ukrainian villages. The whitewashed walls of mazanka houses, nestled among gardens and fields, created a picturesque landscape that continues to define the rural Ukrainian identity. Though modern materials have become more prevalent, the legacy of earthen construction remains an important part of Ukraine’s architectural heritage.

Here, you can check out a contemporary documentary film about the vernacular architecture of Ukraine filmed during the war, where multimedia platform Ukraïner and film studio Craft Story have teamed up for a special five-part documentary series entitled ‘STRIKHA’ (meaning ‘the roof’ in Ukrainian). Based on a long-term expedition throughout all regions of war-torn Ukraine (except those occupied by Russia), the series portrays the country’s authentic and vernacular architectural ‘treasures,’ particularly those hidden in distant villages, away from the main road.

Here’s an example of a contemporary take on Ukrainian earthen building utilizing the wattle, daub, and cobb techniques. The Ukrainian architecture firm of architect Yuriy Ryntovt built the restaurant Pyana Hata in Kharkiv in 1999 (literal translation: “drunk house,” but now you know that khata/hata means not just a house but an earthen plus wooden structure) that may playfully resemble an ancient Neolithic Trypillian culture aesthetics. The building area is 350 m2, and the site area is 0.4 hectares.

Yuriy Ryntovt is born in 1966. Head of the creative workshop Ryntovt Design (Kharkov), specializing in architectural design, furniture, and interior design. Co-founder and artistic director of the theater and concert club “RODDom.”

19th century

19th century