The Poeh Center Museum Building is the tallest adobe building in New Mexico. The four story tower was completed in 1996.

Architecture, Art, Design, and Culture using of mud, clay, soil, dirt & dust.

The Poeh Center Museum Building is the tallest adobe building in New Mexico. The four story tower was completed in 1996.

For 17 years, from 1911 to 1928, Denny Hill Park — Seattle’s first — was 60 feet above its regraded surroundings, then, in the name of progress, it was leveled. Architect Jerry Garcia is proposing that the park be re-built, along with a museum-like pavilion constructed of rammed-earth exterior walls that, amazingly, could be made of dirt from the original Denny Hill

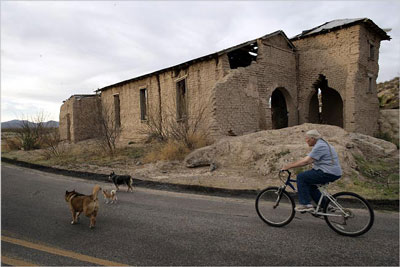

The weather-beaten adobe walls of a neglected Roman Catholic church with its three sun-dried arches are the only reminder that Ruidosa, an isolated hamlet of 19 people hugging the Mexican border in West Texas, once flourished as a cotton-growing center with more than 300 residents, its own cotton gin and a half dozen cantinas. photo by Rick Scibelli Jr. for The New York Times

Many web sites explicitly state that Monticello is constructed of rammed earth. Here are just a few quotes and the links:

“Some of the oldest structures still standing were made of rammed earth, including the Great Wall of China, as well as such later domiciles as Monticello, home of Thomas Jefferson” http://www.forbes.com/2001/11/09/1109how.html

“By the late 1700’s and early 1800’s German immigrants had established rammed earth in New York and Pennsylvania. Some of these old homes are still in use, although it is difficult to document them because the dwellers themselves have no idea of wall constructions. It is hard to say who the enthusiasts were along the mid-eastern seaboard, but a least one was Thomas Jefferson. The essence of “owner-coordinator”, Jefferson built his home, Monticello, of rammed earth and he was vociferous about urging other colonists to do likewise.”

www.adobe-home.com/html/rammed_earth_history.html

Huguenot settlers in North and South Carolina used this technique, and it is believed that some of the outbuildings at Monticello, Jefferson’s home in Virginia, were made of rammed earth.

thelibrary.springfield.missouri.org/lochist/periodicals/bittersweet/su79c.htm

According to Eric Johnson, the Library Services Coordinator at the Jefferson Library, Monticello was not constructed of rammed earth, but instead was built of bricks made here on the property.

Probably the single best source to turn to on the construction of Monticello is by Clemson University Professor Jack McLaughlin’s Jefferson and Monticello : The Biography of a Builder (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1988). McLaughlin states that: “To my knowledge, Jefferson did not use rammed earth as a construciton technique, certainly not at Monticello or Poplar Forest. These two buildings have been so thoroughly researched that any unusual materials would have turned up. Jefferson made his own bricks with slave labor so brick was readily available, as was stone rubble used for cellars. He did use rustication on the exterior of parts of Monticello, covering brick with stucco and sand and then scribing it to make it look like cut stone.”

Thomas Jefferson was very well aware of rammed earth. A mention of rammed-earth construction in a footnote to a 15 March 1810 letter sent by Thomas Jefferson to Stephen W. Johnson. Evidently, Mr. Johnson dedicated the first American treatise on rammed-earth construction to Jefferson, “Rural economy: containing a Treatise on Pisé Building” (New Brunswick, 1806). More information about the exchange of letters and Mr. Johnson can be found on page 297 of Volume 2 of the “Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series” (Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2004- ).

There are many more references to rammed earth and/or pisé construction in Jefferson’s letters (and in the footnotes of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson). And they do seem to support the earlier conclusion that he did not use it to build Monticello. In a footnote to a letter from the father of modern rammed earth construction, François Cointeraux on 16 June 1789 regarding rammed-earth construction, the editor of the Papers noted the following (Vol. 15, p. 185):

“TJ, who must have known about rammed-earth construction from his reading of Pliny and who had seen specimens of this type of building in the South of France in 1787, was inclined to question ‘how far it may offer benefit [in America] superior to the methods of the country founded in the actual circumstances of the country as to the combined costs of labour and materials, and the circumstances of durability comfort and appearance’ (TJ to Short, 13 Apr. 1800, acknowledging receipt of ‘the book on the method of building in Pisé,’ which must have been François Cointeraux’ Ecole d’architecture rurale, Paris, 1790-1791, a copy of which was in his library. . . . While he was secretary of state, TJ was asked by Washington to comment on Cointeraux’ proposal to come to America to demonstrate his method and TJ’s response was one of indifference (TJ to Washington, 18 Nov. 1792).”

The footnote continues with a brief discussion of pisé buildings in America, noting: “Others (of both pisé and mud-wall construction) are extant in Virginia, though there is no evidence that TJ had any connection with them or any application of either method. He advised his friend John Hartwell Cocke concerning the design of Bremo, but it was Cocke who built, in the last decade of TJ’s life, no less than four dependencies in pisé at Bremo Recess and at Upper Bremo. . . . Cocke was evidently the first in Virginia to employ pisé and mud-wall construction: ‘I know of no person in our country who has built mud walls but myself,’ he wrote years later. “It was not an original conception of mine, it having been in use for centuries in Europe,” (quoted by Philip St. George Cocke, “On the Value, and Mode of Construction of Mud Walls, for Farm Buildings and Enclosures,” Farmer’s Register, IV [July, 1836], 172-4; N. Herbemont, “On the Use of Pisé in Constructing Houses and Fences,” same, III [Dec. 1835], 490-2; A. W. Bohannon, Old Surry, Petersburg, Va., 1957, p. 30).”

There are two other articles that link Jefferson to Cointeraux: “Thomas Jefferson and François Cointereaux, Professor of Rural Architecture in Revolutionary Paris,” published in Architectural History, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain, volume 48 (2005), pp. 173-206 and another article will be published in 2006 in that same journal entitled “François Cointereaux’s Ecole d’Architecture Rurale (1791-92) and its influence in Europe and the Colonies.”

The written evidence seems to indicate that while Jefferson was familiar with rammed-earth construction, he didn’t employ it and it may have been John Hartwell Cocke might have been the first to do so in this region.

thanks to Eric Johnson, Library Services Coordinator at the Jefferson Library, and Clemson University Professor Jack McLaughlin for their valuable assistance

Rammed Earth N51 is a sixty-foot-long freestanding rammed earth wall built by a team of students and staff at MIT during the summer of 2005. The project combines research on historical and contemporary rammed earth methods with material research undertaken in the geotechnical laboratory at MIT. [ previously ]

Lloyd and Ted Ober document the construction of a rammed earth house in Louisiana. Good documentation with photos, video and text.

The Elser House by Richard Eribes & Mary Hardin protects from the scorching midday and afternoon heat with a generous roof shades the house and creates places of respite in the courts and patios. When the monsoons come, rain gathers on the roof and plunges off above the patio in a single stream, to be captured in a stone basin below.

A team of MIT architecture students built a wall behind the MIT Museum of rammed earth using a combination of 30 percent Boston Blue Clay mixed with sand and gravel. Twelve tons of this clay, common at depths of 30 to 60 feet in the metropolitan Boston area, came from the excavation site of a new building at Harvard. “The wall will serve as a long-term test of rammed earth in New England, allowing us to observe the way various soil types used in construction stand up to the climate,” said Joe Dahmen, a graduate student in architecture who is leading the project. [ more at livescience ]

“Node 1” is a conceptual architecture project by French Architect François Roche which lacks most of the usual architectural accoutrements: blueprints, material suppliers, subcontractors. Instead, Roche imagines a programmable assembly device dubbed the “viab,” a construction robot capable of improvising as it assembles walls, ducts, cables, and pipes. A viab would produce structures that are not set and specific, but impermanent and malleable – merely viable – made of a uniform, recyclable substance like adobe.

The closest thing to a viab today is a modest mud-working robot, called “contour crafter”, invented by Behrokh Khoshnevis, a professor of engineering at the University of Southern California. Two years ago, California-based architect Greg Lynn was talking to Khoshnevis about the same topic. [ 1 | 2 | 3 ]

Perhaps nowhere is the blending of modernity and the tradition of earth building more evident than at the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. Casa Grande was constructed between ad 1200-1450 by the Native American Hohokam near Phoenix, Arizona. In 1928, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., son of Frederick Law Olmsted the landscape architect most famous for the earthwork of Central Park in New York City, was acting as an adviser to the National Park Service. The desire by the National Park service was to create a shelter that both protected the ruins, while allowing them to have hierarchical presence. The Olmsted Jr. design was completed on December 12, 1932.