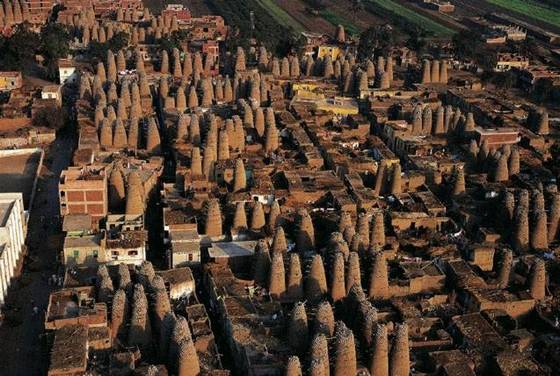

Yakhchal in Yazd Province

By 400 BC, Persian engineers had mastered the technique of storing ice in the middle of summer in the desert. The ice was brought in during the winters from nearby mountains in bulk amounts, and stored in a Yakhchal, or ice-pit. These ancient refrigerators were used primarily to store ice for use in the summer, as well as for food storage, in the hot, dry desert climate of Iran. The ice was also used to chill treats for royalty during hot summer days and to make faloodeh, the traditional Persian frozen dessert.

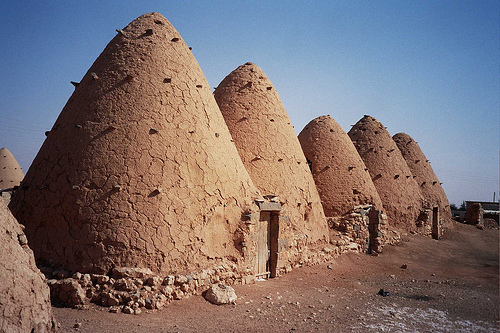

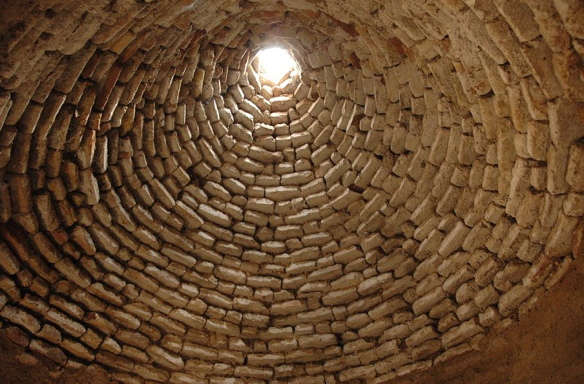

Aboveground, the structure is comprised of a large mud brick dome, often rising as tall as 60 feet tall. Below are large underground spaces, up to 5000m³, with a deep storage space. The space often had access to a Qanat, or wind catchand often contained a system of windcatchers that could easily bring temperatures inside the space down to frigid levels in summer days.

NimVar Yakhchal

The Yakhchal have thick mud brick walls that are up to two meters thick at the base, made out of a special mortar called s?rooj, composed of sand, clay, egg whites, lime, goat hair, and ash in specific proportions, and which was resistant to heat transfer. This mixture was thought to be completely water impenetrable.

Meraji Yakhchal

The massive insulation and the continuous cooling waters that spiral down its side keep the ice stored there in winter frozen throughout the summer. These ice houses used in desert towns from antiquity have a trench at the bottom to catch what water does melt from the ice and allow it to refreeze during the cold desert nights. The ice is broken up and moved to caverns deep in the ground. As more water runs into the trench the process is repeated.

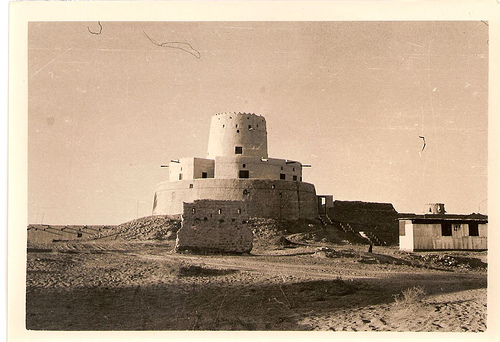

The twin ice-pits on Sirjan, Kerman Province, are surrounded by high walls and were constructed 108 years ago with mud-brick, the ice-pits are surrounded by high walls.