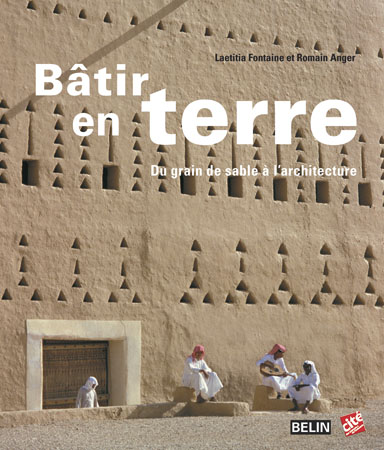

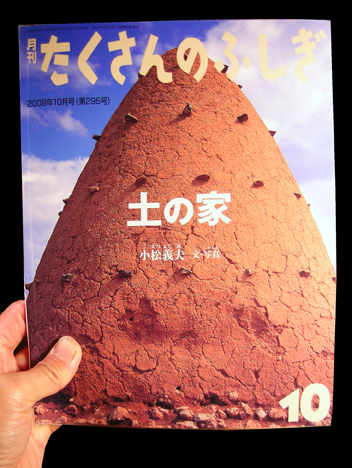

Books on architectural history and theory often overlook mud and dust as a material of architecture and cities. As author David Gissen points out in his new book, “Subnature: Architecture’s Other Environments “, the eradication of mud from urban environments is often seen as a form of cultural advancement. “Massive paving projects were undertaken to remove muddy pockets from the centers of cities, and drainage efforts eliminated mud from most public parklands. The appearance of mud [in the ninetieth and twentieth centuries] became emblematic of urban engineering failures and impending pathologies”, writes Gissen. He then goes on to describe the expanded potential for this material from a historical and theoretical perspective in projects such as de Paor architects pavillion for the Venice Bienale, which was constructed of 21 tons of Irish peat and Otero-Pailos’s The Ethics of Dust, and experimental preservation project which captures an interiors dust in latex that is then assembled as an interior facade. The book is not about fashionable topics surrounding sustainability and ecology. With chapters on smoke, dankness, debris, exhaust, weeds and other counter-architectural conditions, Gissen seeks to expand one’s perception of truly alternative materials in a positively original way.

“, the eradication of mud from urban environments is often seen as a form of cultural advancement. “Massive paving projects were undertaken to remove muddy pockets from the centers of cities, and drainage efforts eliminated mud from most public parklands. The appearance of mud [in the ninetieth and twentieth centuries] became emblematic of urban engineering failures and impending pathologies”, writes Gissen. He then goes on to describe the expanded potential for this material from a historical and theoretical perspective in projects such as de Paor architects pavillion for the Venice Bienale, which was constructed of 21 tons of Irish peat and Otero-Pailos’s The Ethics of Dust, and experimental preservation project which captures an interiors dust in latex that is then assembled as an interior facade. The book is not about fashionable topics surrounding sustainability and ecology. With chapters on smoke, dankness, debris, exhaust, weeds and other counter-architectural conditions, Gissen seeks to expand one’s perception of truly alternative materials in a positively original way.

Book Description

We are conditioned over time to regard environmental forces such as dust, mud, gas, smoke, debris, weeds, and insects as inimical to architecture. Much of today’s discussion about sustainable and green design revolves around efforts to clean or filter out these primitive elements. While mostly the direct result of human habitation, these ‘subnatural forces’ are nothing new. In fact, our ability to manage these forces has long defined the limits of civilized life. From its origins, architecture has been engaged in both fighting and embracing these so-called destructive forces. In Subnature, David Gissen, author of our critically acclaimed Big and Green, examines experimental work by today’s leading designers, scholars, philosophers, and biologists that rejects the idea that humans can somehow recreate a purely natural world, free of the untidy elements that actually constitute nature. Each chapter provides an examination of a particular form of subnature and its actualization in contemporary design practice.

The exhilarating and at times unsettling work featured in Subnature suggests an alternative view of natural processes and ecosystems and their relationships to human society and architecture. R&Sien’s Mosquito Bottleneck house in Trinidad uses a skin that actually attracts mosquitoes and moves them through the building, while keeping them separate from the occupants. In his building designs the architect Philippe Rahm draws the dank air from the earth and the gasses and moisture from our breath to define new forms of spatial experience. In his Underground House, Mollier House, and Omnisport Hall, Rahm forces us to consider the odor of soil and the emissions from our body as the natural context of a future architecture. [Cero 9]’s design for the Magic Mountain captures excess heat emitted from a power generator in Ames, Iowa, to fuel a rose garden that embellishes the industrial site and creates a natural mountain rising above the city’s skyline. Subnature looks beyond LEED ratings, green roofs, and solar panels toward a progressive architecture based on a radical new conception of nature.