Tiébélé’s houses are an outstanding example of vernacular architecture as cultural art. They reveal how a community’s beliefs, social structure and environment can be woven into the very fabric of its buildings. The communal process with all villagers building and decorating each home is a model of collaboration and knowledge sharing.

In each family compound, men do the work of building in the dry season, while women handle all decorative painting and plastering just before the rainy season. Women are the sole keepers of the mural designs, they learn the motifs from elders and pass them to daughters through hands-on training. Because this is a vernacular tradition, there is no formal architect and knowledge is transmitted orally. Builders and painters all live locally in Tiébélé and nearby Kassena villages, motivated by communal duty and cultural obligation.

Because every villager participates, house building is a cultural rite. The communal construction and decoration serves as a vital means of passing Kassena culture across generations. Women, as the “sole guardians” of the mural tradition, use the process to teach daughters the ancestral patterns during large gatherings. In this way, intangible knowledge is preserved.

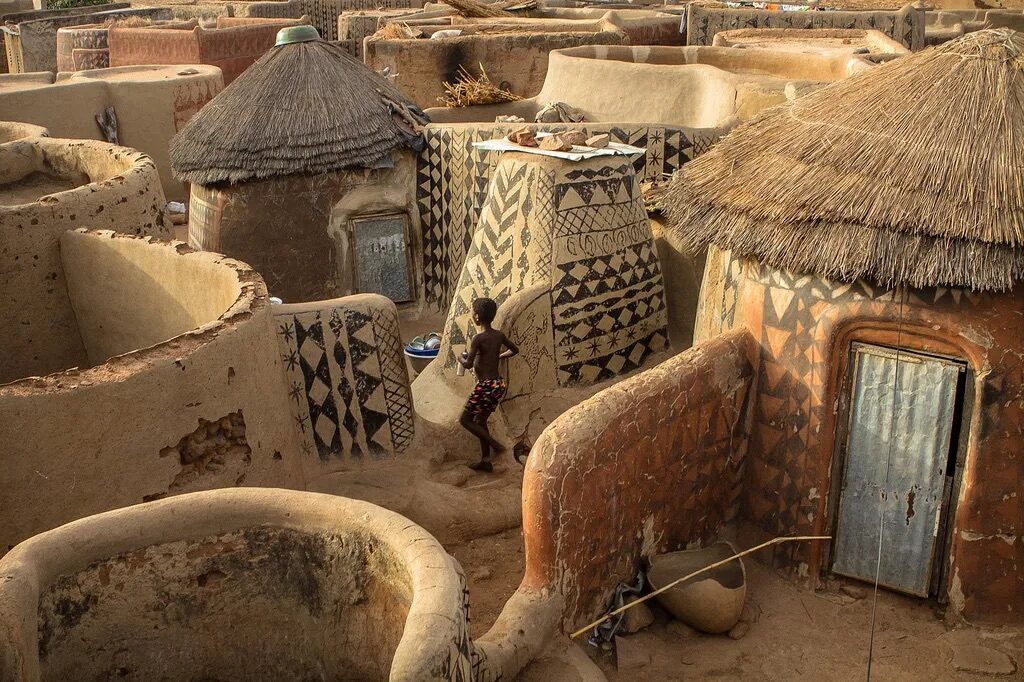

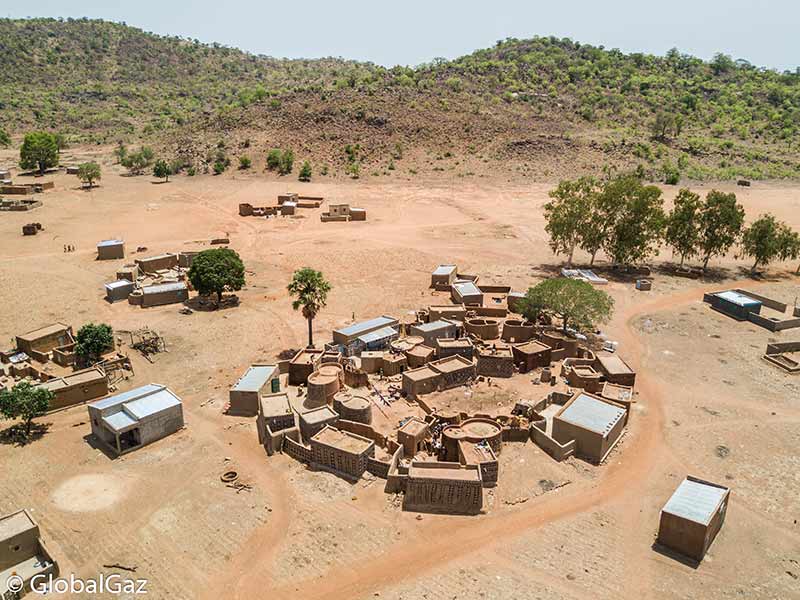

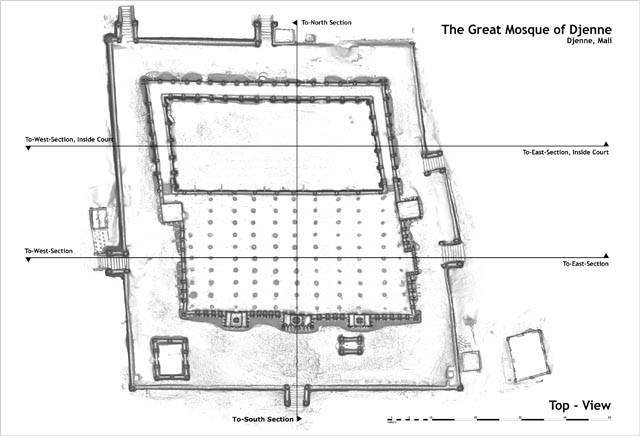

The core of the village is the Royal Court of Tiébélé, a walled clan compound that serves as the chief’s residence and ceremonial center. From this core, family compounds with painted houses grow outward in a roughly circular, fractal pattern. A narrow labyrinth of alleys links the houses, which aids communal life and defense, reflecting a tightly clustered form.

Tiébélé’s architecture is a living expression of Kasena culture. The built form and murals encode the community’s social organization, beliefs and history. For example, the compound is organized into five social domains and the choice of house shape immediately signals the occupant’s age, gender, and status. Dinia houses (30–40 m²) are irregular hourglass-shaped houses formed by two circular rooms joined by a narrow corridor reserved for elders, widows, unmarried women and children. These sprawling structures often form the nucleus of a compound.

Mangolo houses (20–30 m²) are a simple rectangular hut used by young married couples. It is a more recent addition to Kasena architecture signifying social transition. Interiors may have a clay bench or seating ledge along one wall. These rectangular houses line the edges of the compounds or fill remaining plots.

Adolescent or unmarried men live in Draa huts (9–12 m²), a round single‑room with a thatch roof and an opening at the top under the eaves for ventilation. The Draa keeps community youth together and allows elders to oversee them easily, and the low door and dark interior teach discipline and security. Each family compound also contains outside kitchens and hearths, granaries, silos, and small altars or shrines to ancestors.

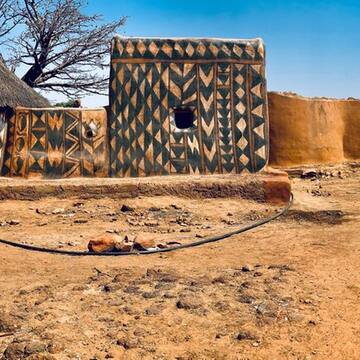

Most strikingly, every wall is a painted canvas of abstract symbols. The facades display red, white and black geometric murals (triangles, crosses, zigzags, animal and plant motifs). These motifs have deep meanings referencing Kassena folklore, animism and daily life (stars for hope, arrows for defense, animals for fertility and protection). While the particular symbols vary, every Kassena home is elaborately painted to express identity and beliefs, and to distinguish it from others in the village.

The architecture also serves practical needs. Thick earth walls stabilize indoor temperatures and resist attacks, small openings protect privacy and security, and the annual repainting waterproofs the walls just before the rainy season. In this harsh environment, such design is both symbolic and sensible, a key reason the Kassena have kept it unchanged for centuries.

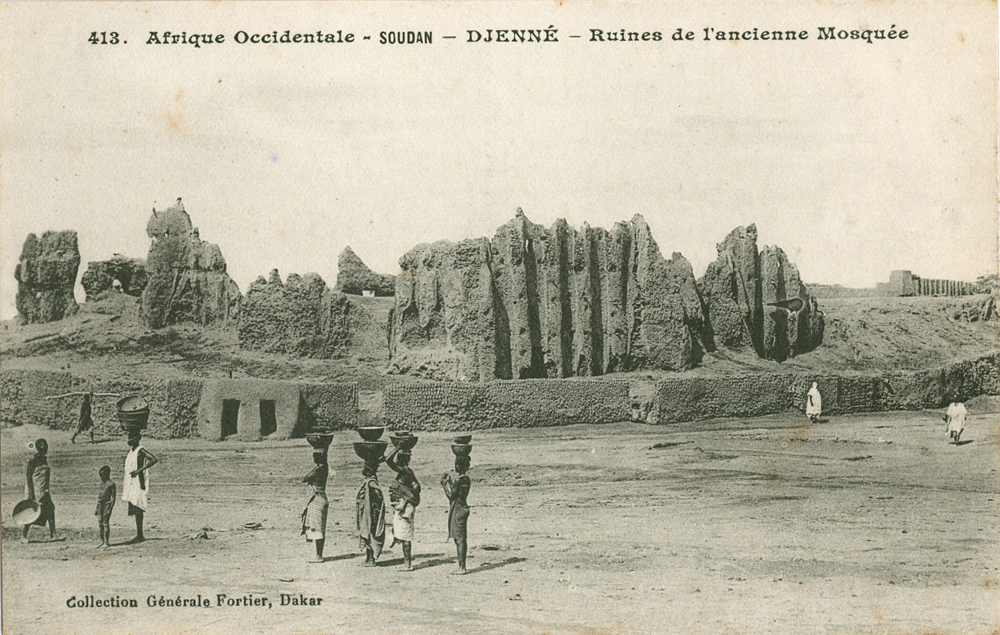

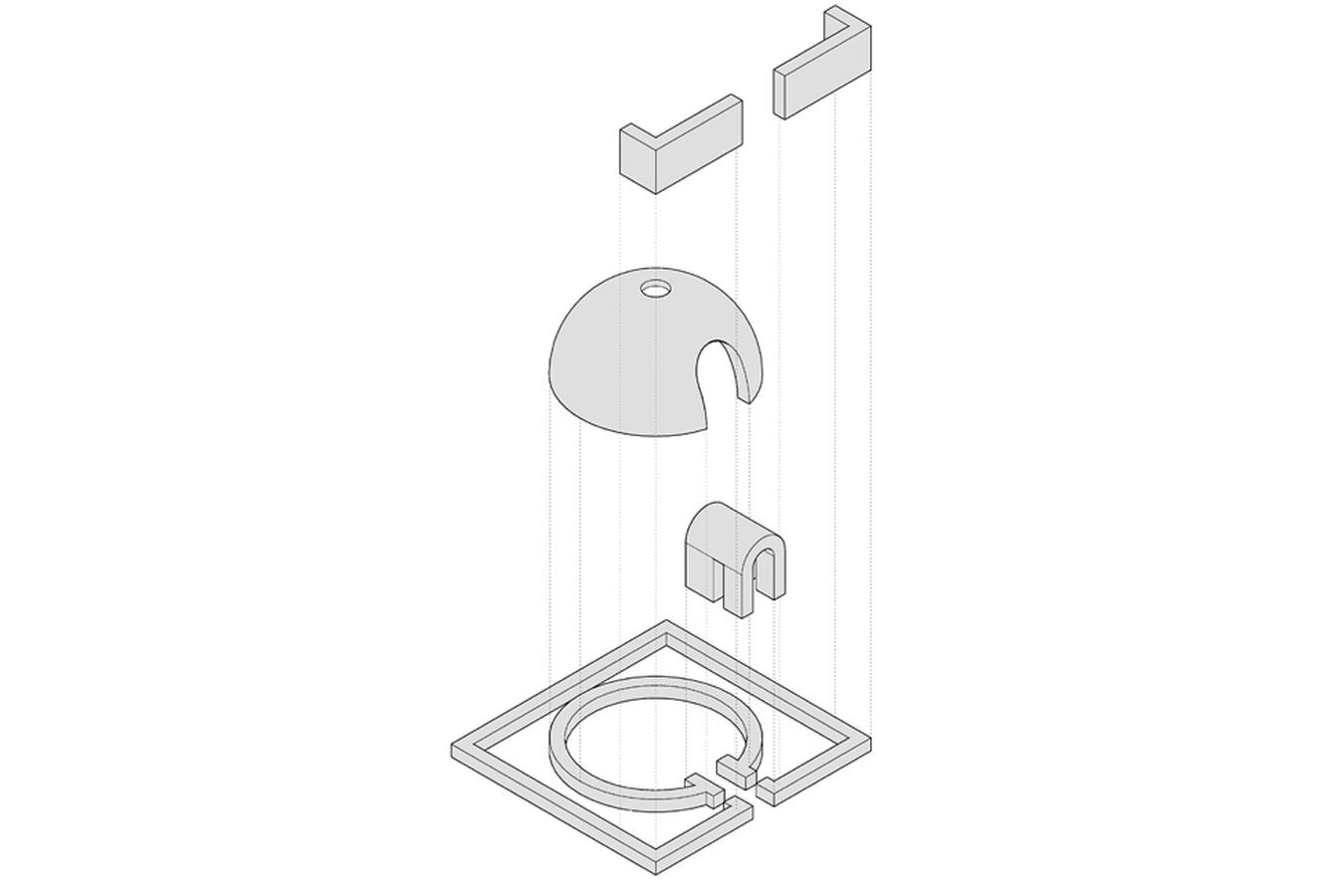

Houses are built entirely from local natural materials. Walls are made of earth mixed with chopped straw and cow dung, either molded by hand or formed into adobe blocks. The walls are around 30 cm thick to buffer heat and cold. Foundations use rough stone or fired laterite to protect from erosion. Ceilings are low, often two meters high or less to expedite plastering. Roofs are flat made with wooden beams overlain by layers of packed earth or clay then laterite. This layered roof when compacted and patched with dung sheds rain but must be periodically re-plastered.

Construction is communal and new houses are built during the dry season. Houses have intentionally minimal openings as a defense measure inherited from times of conflict, with almost no windows and doorways only about two feet high, forcing entrants to stoop. Just before the rainy season, all village women gather to plaster and decorate each house. They first roughen and coat the dry mud walls, then paint by hand in the planned design. Pigments are prepared from local minerals mixed with water and clay (red from laterite soil, white from chalk, black from charred basalt or plant charcoal). After painting, each color is burnished with a stone, and finally the entire surface is varnished with a boiled African locust bean fruit solution. Tools may include feathers, combs or sticks for patterning. Throughout the process, the oldest woman present directs the patterns and sequences, ensuring the motifs are executed properly. Because every household participates, the decoration of a house is as much a social ceremony as a construction task. Family members give food and drinks to workers as payment, ensuring communal participation.

Tiébélé values local materials, sustainability and cultural context. These houses teach that design can be participatory and deeply symbolic, not just functional. In a world of standardized construction, Tiébélé’s earthen buildings remind us of the beauty of craft, community and continuity. The result is an inseparable fusion of architecture and art, every building is a cultural statement, unique yet part of a grand communal ensemble.

Citations:

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1713/gallery/&index=37&maxrows=12

- https://globalgaz.com/tiebele-painted-houses/

- https://www.allisongreenwald.com/dora

- https://unusualplaces.org/the-painted-village-of-burkina-faso-africa/#:~:text=But%20it%E2%80%99s%20the%20decoration%20of,from%20the%20leaves%20of%20acacia