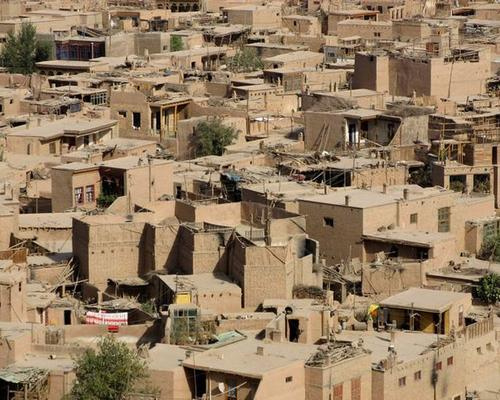

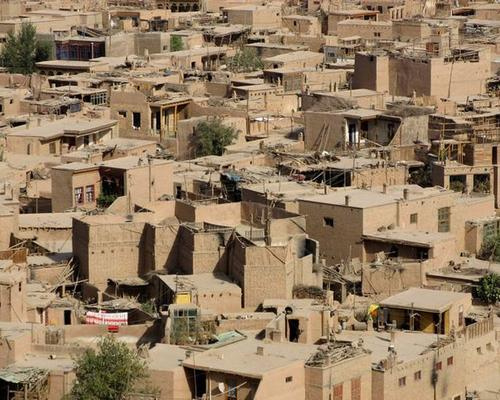

Bulldozers are to raze the mesmerising mud brick old town in the Chinese Silk Road city of Kashgar. Visit soon before its vibrant street culture is lost, or better, help save Kashgar.

Architecture, Art, Design, and Culture using of mud, clay, soil, dirt & dust.

Bulldozers are to raze the mesmerising mud brick old town in the Chinese Silk Road city of Kashgar. Visit soon before its vibrant street culture is lost, or better, help save Kashgar.

Previously we reported that the Israeli siege on Gaza led to citizens constructing their houses with mud brick due to a lock on billions of dollars in reconstruction funds pledged by the international community. The ingenuity also stems from a resource created by the excavation of border tunnels, primarily in the Rafah region, used to transport goods from Egypt. When tunnels are dug, mounds of mud are created, and this mud is considered prime for the production of mud bricks. Under the siege, and due to Gazans’ loss of hope that reconstruction projects will rebuild the thousands of houses and institutions destroyed by the Israeli occupation, particularly during its New Year offensive, many homeowners have begun to explore the mud alternative.

Photo credit (left), Photo credit (right)

“Hamas is actually supporting the mud-brick housing movement and has pledged money and assembled a special engineering committee to investigate a pilot project that will test a multistory school to determine just how safe and plausible building more widespread with mud brick can be. Of course, all of this has spawned a new temporary economy in tunnel mud removal and brick manufacturing, and the engineering itself is quite antiquated but none the more outdated. They’re using combinations of mud, sand, salt, and straw, and in some cases rubble to forge bricks and build basic homes. Some have already been said to have withstood elements of winter rains and harsh summer sun….It’s almost as if the tunnels had been turned inside out, sort of poetically unraveled overland as a result of the Israeli assaults, and now offer the dual benefit of both relief housing while also keeping the essential corridors of underground commerce alive. In some ways it’s just good old-fashioned poetic justice bound with some gritty irony. “ writes Subtopia.

Several videos about the mud brick houses are available on YouTube. In one, the daughter of Nidal Eid, a 35 year-old who constructed his own mud brick house, states, “Daddy makes everything out of mud, but he can’t make me mud toys.” In another video it is suggested that building with mud brick is “a step back in time.” But is it a step back, or a step forward, creating a Palestinian identity through architecture drawn from tunnels that “represent the frontier of Gaza’s fight for geo-economic autonomy…amazing blueprints as uprooted spaces edited into fresh new infrastructure now in plain view”, as mentioned in the Subtopia essay. “Mud is valuable”, mentions a builder of a mud brick house in another video.

[Gaza’s Mud Brick Homes | Gaza’s Gritty Mixture of Dirt, Despair Produces Houses of Mud | Mud, mud, glorious mud. Nothing quite like it for beating the Israeli blockade | Subtopia: Over the Siege ]

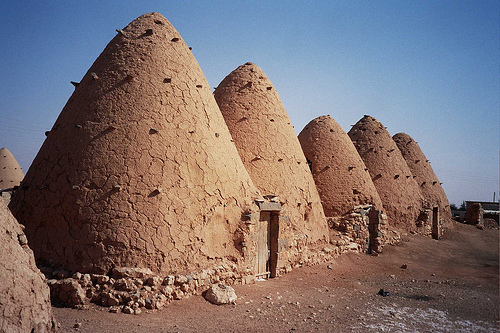

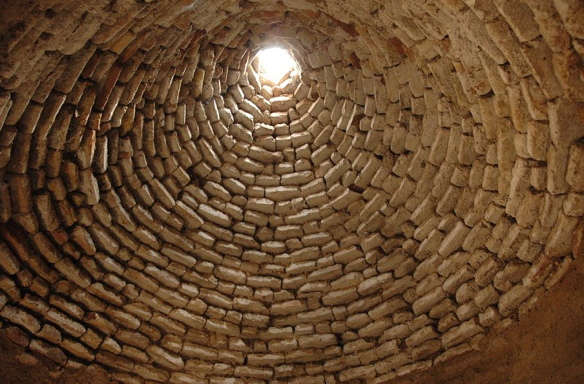

Designed for the desert climate, the beehive homes keep the heat out in a few ways. Their thick mud brick walls trap in the cool and keep the sun out as well (beehive homes have very few, if any, windows). The high domes of the beehive houses also collect the hot air, moving it away from the residents sleeping at the bottom of the house.

Inside, its high dome serves to collect the hotter air, and outside to shed rainfall instantly, before the brick can absorb it and crumble. Its thick roof-cum-wall is an excellent low-velocity heat-exchanger, and keeps interior temperatures between 85° and 75° F. while outside noon-to-midnight extremes range from 140° to 60°.

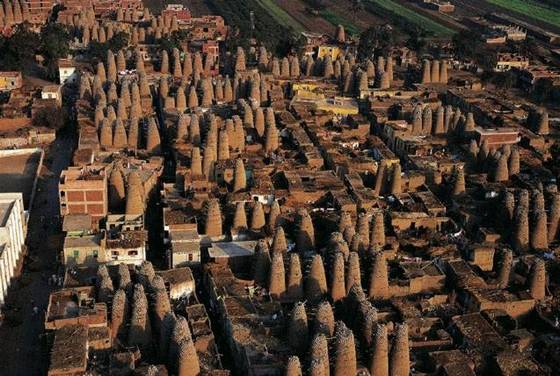

Pigeon houses at Mit Gahmr, Egypt

Pigeon is a part of the daily diet in many parts of Egypt and Pigeon houses, or dovecotes, are constructed from mud brick create an artificial mountainous topography. The droppings are also a valuable source of fertilizer and the houses are so ubiquitous that they are also part of the Egyptian national identity. The dovecote typology can be found throughout the world and Earth Architecture has previously featured the palomares of Spain.

Interestingly, the Egyptian pigeon houses remind one of the recent work of architect Vicente Guallart, who in his project The Re-Naturalization of Territory, attempts to create what could be considered as dovecotes for biotechnology and cinema in Tarragona, Spain.

Building earthen structures like bread ovens and small animal pens is a technique many Palestinians are familiar with, but extending the method to houses isn’t a notion that has taken hold in Gaza. But Jihad el-Shaar, who lived with his wife and four daughters with extended family wanted to build a home of their own. After waiting for two years, it was apparent that the siege would make cement unavailable so he decided to build his house of mud.

Photo by Yasmina Rossi.

“The allure of elegant earthen architecture can be life-changing. At least that was the case for urbane New Yorker Simone Swan, who in the 1970s became fascinated with the ideas and designs of renowned Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy. Then the 40-something executive head of the Houston-based Menil Foundation, Swan moved to Cairo to study with Fathy. She became his most passionate advocate, and transplanted his adobe building techniques to the Southwestern United States.”

Abari, a socially and environmentally committed research,design and construction firm that examines, encourages, and celebrates the vernacular architectural tradition of Nepal. In this recent project, the dome will be covered with bamboo roof as a protection again heavy tropical rain. The adobe structure is reinforced with bamboo to make it earthquake resitant. This structure is a reception of community structure, which is also being built.

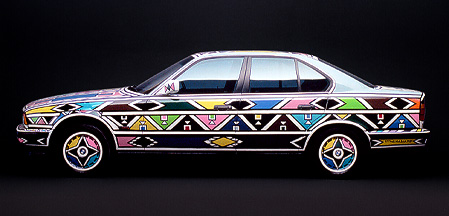

A curious relationship between mud brick architecture,clay and the automobile exists in two very important earthen architecture building cultures: among the Ndebele people of South Africa, whose vividly painted mud brick houses have been transposed to the automobile, and in northern New Mexico where the descendants of the Indigenous Pueblo people and Spanish colonists created a unique style of mud brick architecture from which emerged the invention of the lowrider.

Ndebele

The Ndebele people of South Africa are famous for the the colorful patterns applied to the exterior of their houses, which are made of a mixture of dung, mud, and clay. Their distinctive house-painting style, originally based on a similar but less colourful style originally developed by the Northern Sotho or Pedi, flowered and achieved its creative pinnacle within the almost slave-like conditions which the Ndebele endured on the white-owned farms of the south-eastern Transvaal during the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century.

The almost exclusively female creators of these arts have for decades been borrowing elements from the social and cultural repertoires both of their neighbours and of modern industrial society. Peter Rich writes, “The strength of Ndebele spatial models and aesthetic grammar allowed them to invest images reinterpreted from other cultures, with their own symbolic meaning. They had an affinity with the stylised art deco that was prevalent in cities such as Pretoria in the 1940s and ’50s. The changing trends in Western society, notably the American car culture of the ’50s, fashion and infatuation with images of power/electricity/jet aeroplanes, were other catalysts. ‘We see what we want to see and make it our own’, proclaims a Ndebele matriarch.”

Application of paint to earthen wall

Because of the striking designs adorning the houses, tourists drove great distances to see the Ndebele, often from as far away as Johanasburg, which was 100 miles away. According to Elizabeth Ann Schneider, the Ndebele women noticed the license plates on the cars and although they could not read them, they liked the shapes of the letters and numbers and began to paint them on their earthen walls. They mirrored the shapes of these forms to create symmetrical patterns on the front of their houses. Wavy designs known as “tire tracks” are still sometimes applied to walls and also appear on floors.

Modern “BMW” Ndebele House

‘Mural decoration is the prerogative of the woman; it denotes her unique and intimate relationship with the indlu (home) and her passive response to being exploited socially and politically,’ wrote Margaret Courtney-Clarke in Ndebele, but with the pressures of a modern era, the Ndebele women became increasingly dependent upon the automobile to find work in cities that were a good distance from their villages. This cultural shift led to the application of Ndebele motifs, which until then used the car as inspiration, to the car itself.

Car decorated with Ndebele paintings in Pretoria, South africa.

Many Ndebele women became well known for their craft and the most celebrated of these artists is Esther Nikwambi Mahlangu. Born in Middleburg in 1936, she was invited in 1989 to exhibit at the Pompidou Art Museum in Paris. In 1991, she was invited to paint a prototype of the new BMW 525i model. Esther’s car, eleventh in the Art Car Collection, was the first to be decorated by a woman artist and as a black woman artist from a little-known South African community to be included in a prestigious international artistic line-up of artists including Frank Stella, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol and David Hockney made this fact all the more exceptional.

Esther Mahlangu’s Ndebele BMW

In 2008 Mahlangu was invited to paint another car—this time the new Fiat 500.

Mahlangu next to her Fiat 500

Today, calling attention to the automobile’s long relationship with the the architecture of the Ndebele, an old car, painted in this evolving tradition, joins a sign announcing the entrance to the famous mud brick village of Lesedi.

Sign at the entrance to the village of Lesedi.

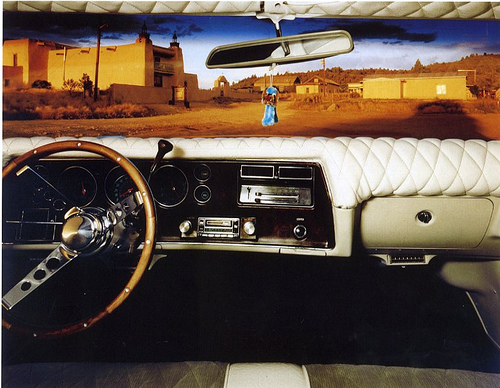

New Mexico

Mud brick was the principal building material Northern New Mexico from the founding of the first European colony in 1598 until the mid 20th century, and hand formed mud had been used in to construct multi-story dwellings for thousands of years prior. Industrialization, mining and the lure of jobs in cities transformed what was largely agrarian society in New Mexico into a society increasingly dependent upon the automobile to travel the great distances from the isolated villages to cities and the mines in central Colorado.

The San José de Gracia Church, built between 1760 and 1776 and considered a model of the adobe architecture found throughout New Mexico. Here the church can be seen through the windshield of Levi Lobato’s 1972 Chevrolet Monte Carlo.

From the desire to bring with them a piece of home from a landscape in which the people were deeply rooted, emerged the lowrider—a chapel on wheels that evoked the essence of the ancient baroque mud brick churches that were at the center of village life.

Dave’s Dream as displayed in the Smithsonian Museum’s former Road Transportation hall, with photomural of the El Santuario de Chimayo, and an assembly of trophies won by this lowrider automobile. Photo by Jeff Tinsley, Negative #: 95-3340

The altar of El Santuario de Chimayo whose color scheme and ornamentation could be seen as influential to “Dave’s Dream”

The long lines of automobiles produced in the 40’s, 50’s, 60’s and 70’s were reminicent of the long corrieras—adobe houses that were composed of several branches of a single family constructed through a series continuous additions as the family grew. The interiors and/or exteriors of the car were often lavishly ornamented, reminiscent of the baroque ornamentation found in the mud brick interiors.

Ruin of a corriera house in San Idelfono, New Mexico and a 1963 Impela.

Low-rider Cadillac named “Chimayo,” Chimayo, New Mexico, 1997 by Craig Varjabedian

Today, the mud brick village of Chimayo, New Mexico is considered the spiritual center of the lowrider world and nearby Española, New Mexico is considered the lowrider capital of the world. Today lowrider culture has become a global phenomena, but the ornate vehicles and over-zealous use of hydraulics that tilts the automobiles into torqued positions still recall the leaning ancient mud brick structures of northern New Mexico.

And while lowriding has become a serious artform and mud brick architecture has roots in the sacred, the combination of adobe architecture and the automobile has also been poked fun at in popular culture as evidenced by the adobe car, featured in a Saturday Night Live “fake commercial“, a transcript of which appears below:

Spokesman: These days, everyone’s talking about the Hyundai, and the Yugo. Both nice cars, if you’ve got $3,000 or $4,000 to throw around. But, for those of us whose name doesn’t happen to be Rockefeller, finally there’s some good news – a car with a sticker price of $179. That’s right, $179. The name of the car?

Adobe. The sassy new Mexican import that’s made out of clay. German engineering and Mexican know-how helped create the first car to break the $200 barrier. At this price, you might not expect more than reliable transportation – but, brother, you get it! Extra features: like the custom contour seats, or the beverage-gripping dash. And the money you save isn’t exactly small change!

Jingle:

“Hey, hey, we’re Adobe!

The little car that’s made out of clay!

We’re gonna save you some money

that you can spend in some other way!

Hey, hey, we’re Adobe!

Hey, hey, we’re Adobe!

Adobe!”

Spokesman: Adobe. You can buy a cheaper car. But I wouldn’t recommend it!

Announcer: Not approved for street use in some states. No warranty either expressed or implied. All sales final.

Interestingly, most major automobile manufacturers actually employ clay to visualize their designs before they go into production. This art of designing cars in clay has existed since the 1920’s, just as the Industrial Revolution was beginning to influence the culture of the remote villages of Northern New Mexico and still today, most of the futuristic prototypes found at car shows are clay models crafted with multiple axis computer controlled mills that carve the car from clay based on designs created using 3D modeling software.

High Speed CNC Machine

And as sophisticated machinery is being developed to shape the automobiles of the future out of clay, cumbersome vehicles exist that move across flat terrains, which consume mud and excrete large quantities of mud brick to fuel a growing demand for adobe houses in New Mexico and beyond. Such machinery can be found at The Adobe Factory in Alcalde, New Mexico and can produce 20,000 mud bricks per day.

An adobe machine

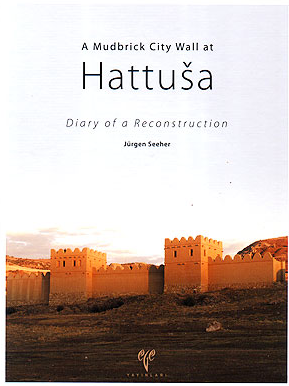

Situated in Central Anatolia, Hattuša remained the capital city of the Hittites from 1650/1600 to around 1200 BC. Here, as recently as 2003 to 2005, the German Archaeological Institute has rebuilt one stretch of the mudbrick city wall. The scope of this project in experimental archaeology has been to recreate a part of the wall using the same materials the Hittites had at hand when they built their original walls so long ago. Each step necessary for the construction was fully documented so as to enable us to assess not only the amount of building materials required but also the manpower and time the Hittites must have invested in the various tasks of construction.

This volume presents the results gleaned from this documentation. From the production of the first mudbrick to the dedication of the finished structure, each and every undertaking has been described in detail and is presented here accompanied by 573 illustrations.

For more information visit:

German Institute of Archaeology (In english, german and turkish)

Hattuscha-webpage (in English, German and Turkish)

This book is published also in German and Turkish:

Die Lehmziegel-Stadtmauer von Hattusa

Bericht über eine Rekonstruktion

ISBN 978-975-807-194-7

Hattusa Kerpic Kent Suru

Bir Rekonstrüksiyon Çal??mas?

ISBN 978-975-807-193-9

The Jahili Fort built in 1898 in Al Ain is now at the centre of an exciting conservation, restoration and development project that will preserve the values of this historic building whilst transforming the site into an active visitor destination.