Who is Christine Howard Sandoval?

Sandoval is an interdisciplinary artist working across media including sculpture, installation, performance, and public art. Her versatile practice allows her to express her conceptual interests through a variety of artistic forms.

Sandoval is currently an Assistant Professor of Interdisciplinary Praxis in the Audain Faculty of Art at Emily Carr University (Vancouver, BC). Howard Sandoval is an enrolled member of the Chalon Nation in Bakersfield, CA. As an artist and writer engaging with timely ecological and social justice issues, Sandoval’s practice is situated within important contemporary conversations around environmentalism, indigeneity, and cultural representation.

https://www.brokenboxespodcast.com/podcast/christine-toward-sandoval

https://www.brokenboxespodcast.com/podcast/christine-toward-sandoval

Cultural Identity and Influences:

As someone of Mexican and European American descent, Sandoval’s multifaceted cultural heritage is a core influence on her artistic vision and the themes she explores.

Her work often engages with questions of land, place, and indigenous environmental knowledge, reflecting her connection to the American Southwest region where she is based.

This cultural hybridity and commitment to representing marginalized perspectives is a key aspect of Sandoval’s artistic identity.

Education and Career:

Sandoval has formal training in the arts, holding a BFA from the University of New Mexico and an MFA from UC Davis.

Her educational background has provided her with a strong technical foundation to realize her conceptual ideas across different mediums.

Over the course of her career, Sandoval has exhibited her work internationally and received prestigious awards and grants, indicating her recognition within the contemporary art world. Howard Sandoval has been awarded numerous residencies including: UBC Okanagan, Indigenous Art Intensive program (Kelowna, BC), ICA San Diego (Encinitas, CA), Santa Fe Art Institute (Santa Fe, NM), Triangle Arts Association (New York, NY).

Examples of her work:

-Coming Home, August 21 – October 31, 2021

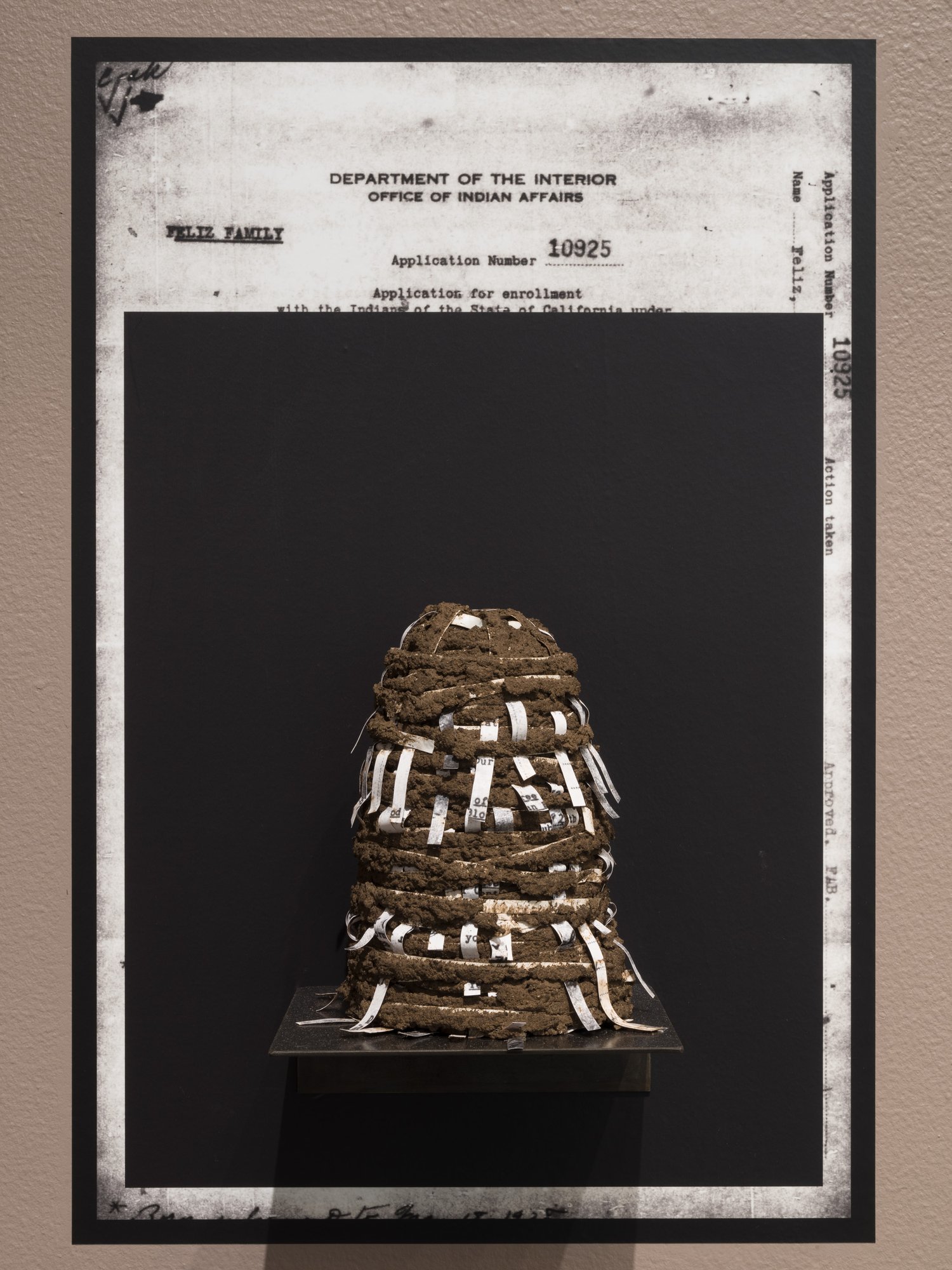

“In Coming Home Christine Howard Sandoval explores the history of California Indigeneity and its relationship to the archive, a place in which collective memory is stored. In California, the documentation constructed by settlers embodies a narrative of erasure but is also embedded with the seeds of Indigenous knowledge paramount to the reconstruction of Indigenous language, cultural practices, and relationships to the land. Howard Sandoval works with the archive to trace the migration of her Chalon Ohlone ancestors, telling the story of her community, her family, and her coming home to California.”

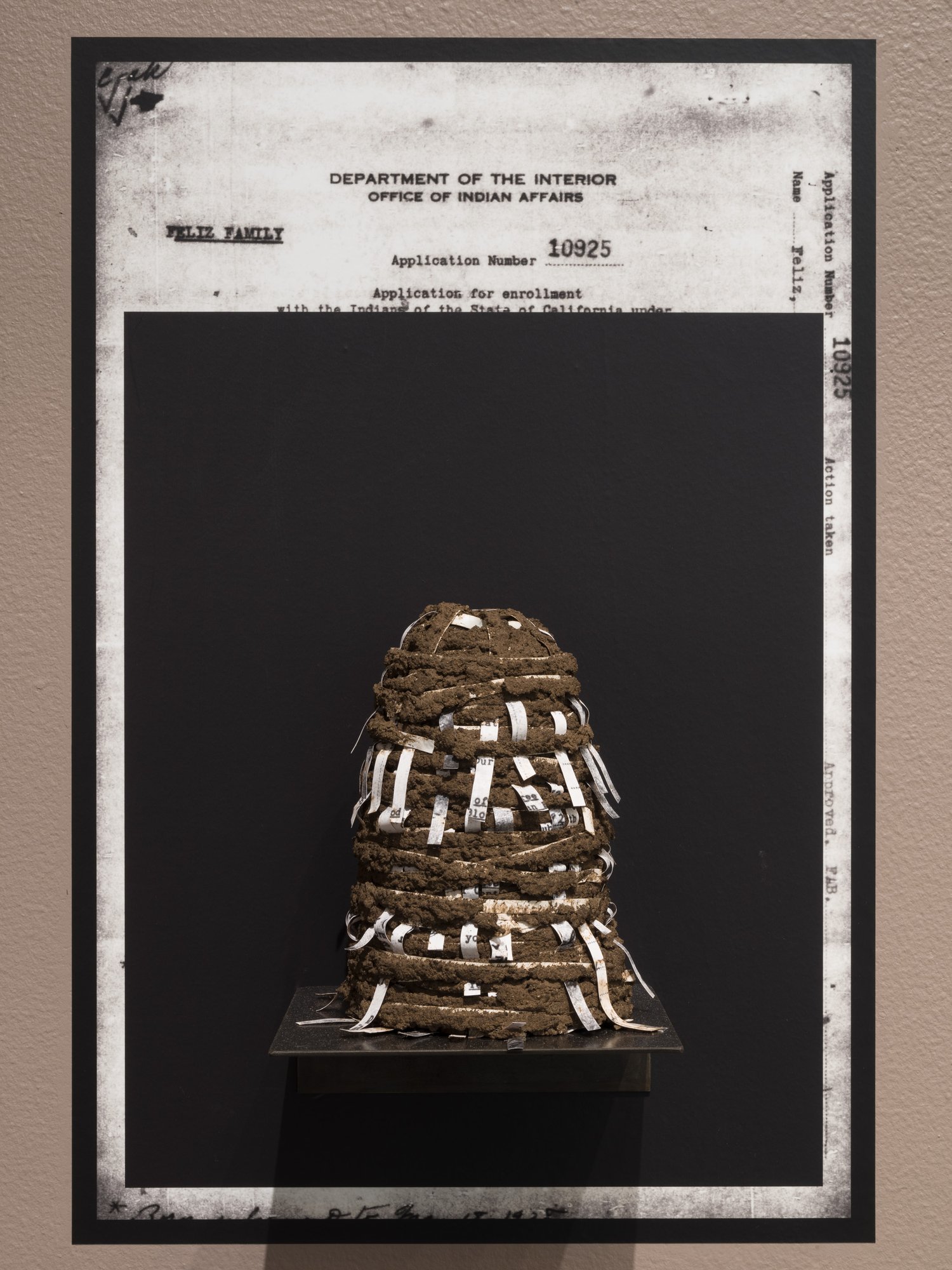

Document Mounds- Application for Enrollment with the Indians of the State of California Under The Act of May 28, 1928 (6 pages), 2021, inkjet print on vinyl, tape, adobe mud, and steel, 24H X 16W X 7D inches each.

Document Mounds- Application for Enrollment with the Indians of the State of California Under The Act of May 28, 1928 (6 pages), 2021, inkjet print on vinyl, tape, adobe mud, and steel, 24H X 16W X 7D inches each.

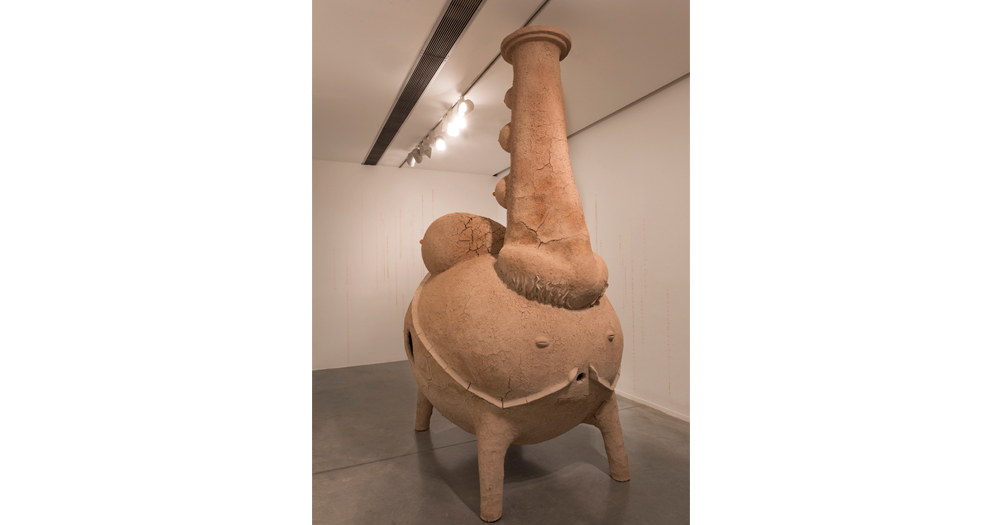

Surveillance Mound, 2021, adobe mud, tape, steel, wood, wire, paint, 89.5H X 19W X 19D inches.

Surveillance Mound, 2021, adobe mud, tape, steel, wood, wire, paint, 89.5H X 19W X 19D inches.

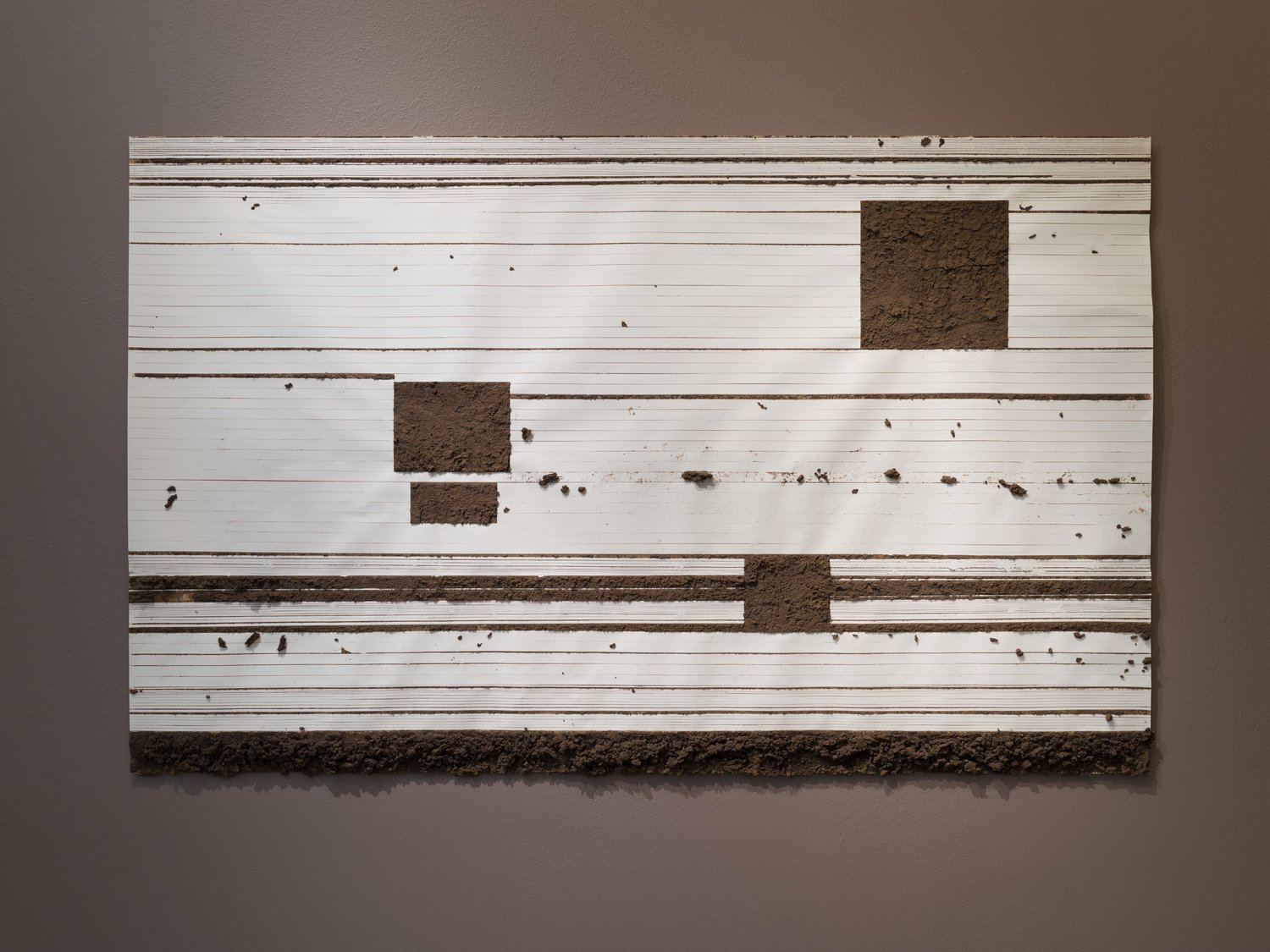

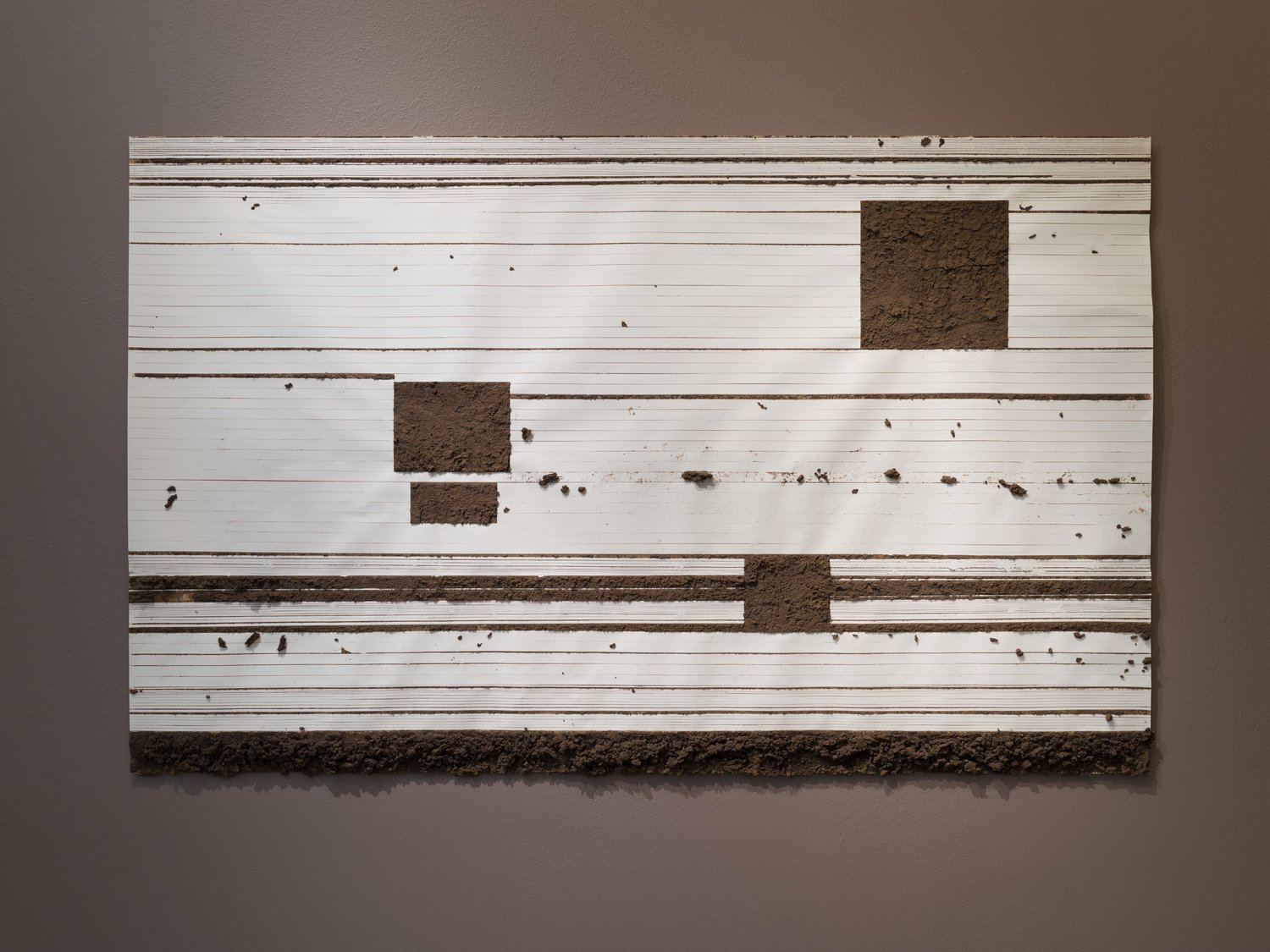

Sending Signals Into The Ground To Form Images Of What Is There To See, 2020, adobe mud on paper, 60 X 96 inches.

Sending Signals Into The Ground To Form Images Of What Is There To See, 2020, adobe mud on paper, 60 X 96 inches.

-The green shoot that cracks the rock, May 27 – July 16, 2022

“Howard Sandoval’s embodied work confronts the complex history and innate interconnection of land and body. As she traces a path to her ancestral home, the artist scrutinizes the narrative of erasure in early North American settler’s records and reassigns power through documentation of embedded Indigenous cultural practices. Her poetic oeuvre seeks to weave a collective awareness back to nature by means of a more cyclical and deepened relationship with land and place.

The land, as an ever-evolving being, plays a central role in Howard Sandoval’s visual language. Taking adobe as her main medium, the artist explores its inherent properties of historical, familial and ecological histories. Adobe mud requires a bodily process to mix soil (sand, silt and clay), water and often straw to form a workable, malleable and ultimately structural material. In this ongoing investigation, she emphasizes the intentionally omitted history of forced labor, land theft, and the violent genocidal actions Indigenous people experienced.”

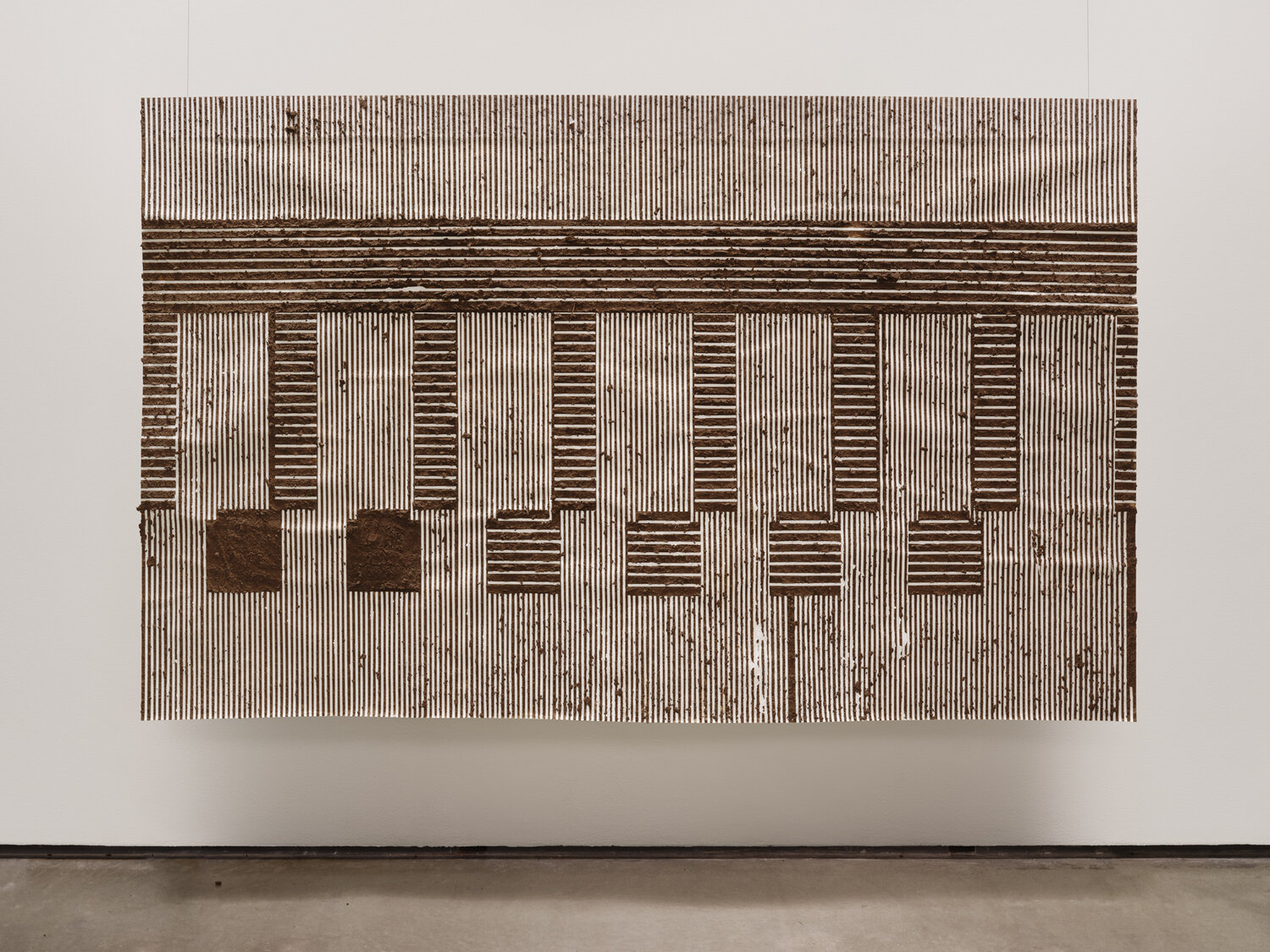

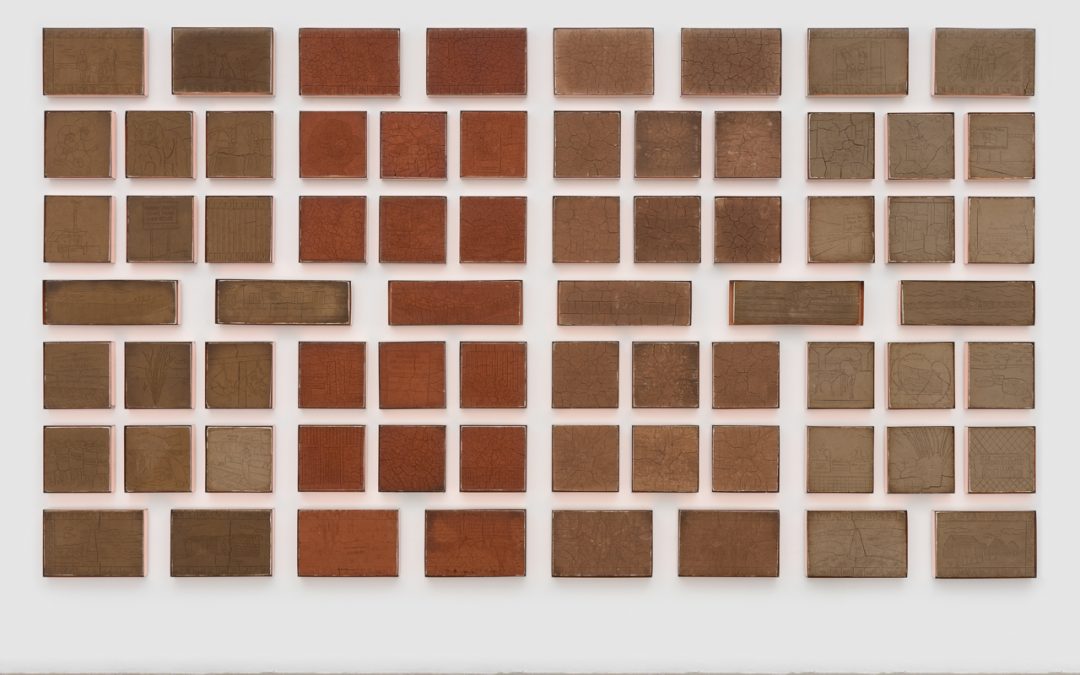

Installation view, the green shoot that cracks the rock, parrasch heijnen gallery, LA, 2022

Installation view, the green shoot that cracks the rock, parrasch heijnen gallery, LA, 2022

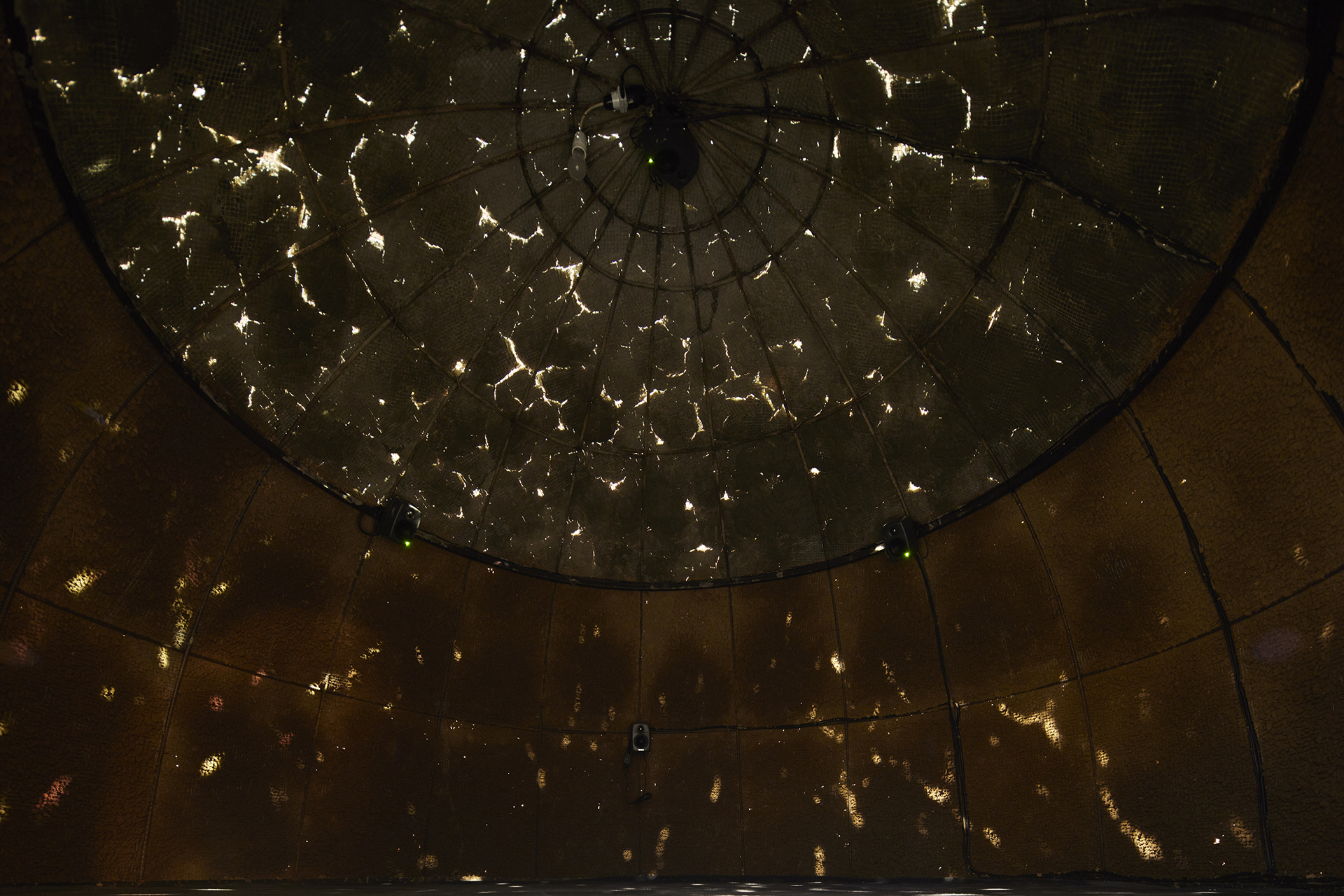

Niniwas- to belong here, 2022, single channel video with audio, TRT 12:23, Sound design in collaboration with Luz Fleming

Installation for the green shoot that cracks the rock, parrasch heijnen gallery, LA, 2022

Stretcher- For The Transportation of Water, 2021 adobe mud, tape, steel, wood, wire 54 x 56 x 27-1/4 inches

Stretcher- For The Transportation of Water, 2021 adobe mud, tape, steel, wood, wire 54 x 56 x 27-1/4 inches

More of her work:

Mound- Angle of Integration, 2020, adobe mud and graphite on paper, 60 X 96 inches.

Mound- Angle of Integration, 2020, adobe mud and graphite on paper, 60 X 96 inches.

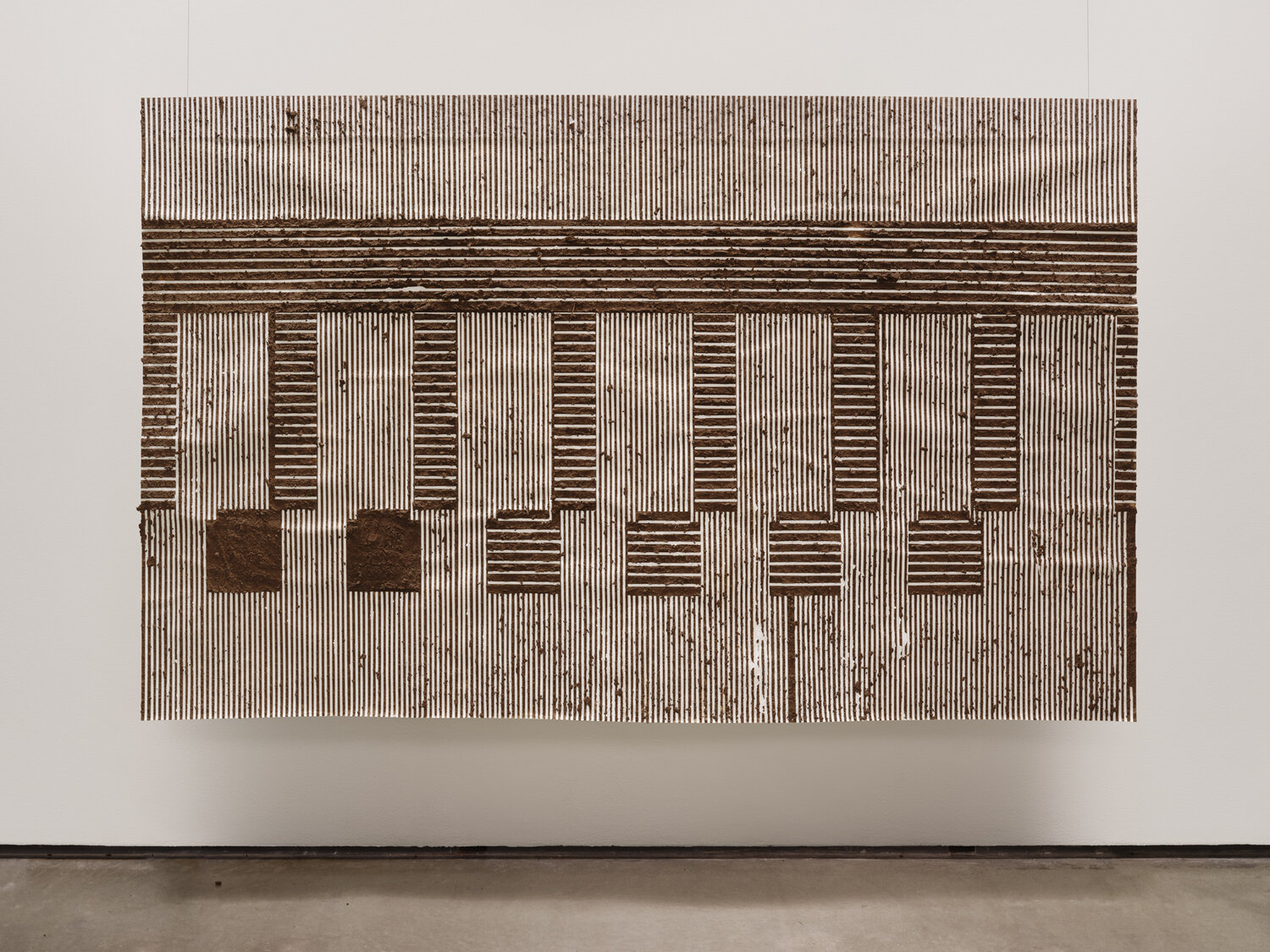

Pillars- An Act of Decompression, 2020, adobe mud and graphite on paper, 60 X 96 inches.

Pillars- An Act of Decompression, 2020, adobe mud and graphite on paper, 60 X 96 inches.

Arch- A Passage Formed By A Curve (detail), 2020. Photo by Scott Massey.

Arch- A Passage Formed By A Curve (detail), 2020. Photo by Scott Massey.

360 VIRTUAL TOUR:

Creative Output:

In addition to her visual art practice, Sandoval is also a published poet and essay writer.

Her literary work, like her art, delves into themes of land, place, and environmental stewardship from an indigenous-influenced perspective.

This dual commitment to both visual and written expression demonstrates Sandoval’s versatility as a creative practitioner.

References:

-https://www.chsandoval.com/home

-https://www.parraschheijnen.com/artists/christine-howard-sandoval

Surveillance Mound, 2021, adobe mud, tape, steel, wood, wire, paint, 89.5H X 19W X 19D inches.

Surveillance Mound, 2021, adobe mud, tape, steel, wood, wire, paint, 89.5H X 19W X 19D inches.

Installation view, the green shoot that cracks the rock, parrasch heijnen gallery, LA, 2022

Installation view, the green shoot that cracks the rock, parrasch heijnen gallery, LA, 2022

Andy Goldsworthy, Earth Wall, 2014, Photograph by The Chronicle’s Sam Whiting.

Andy Goldsworthy, Earth Wall, 2014, Photograph by The Chronicle’s Sam Whiting.

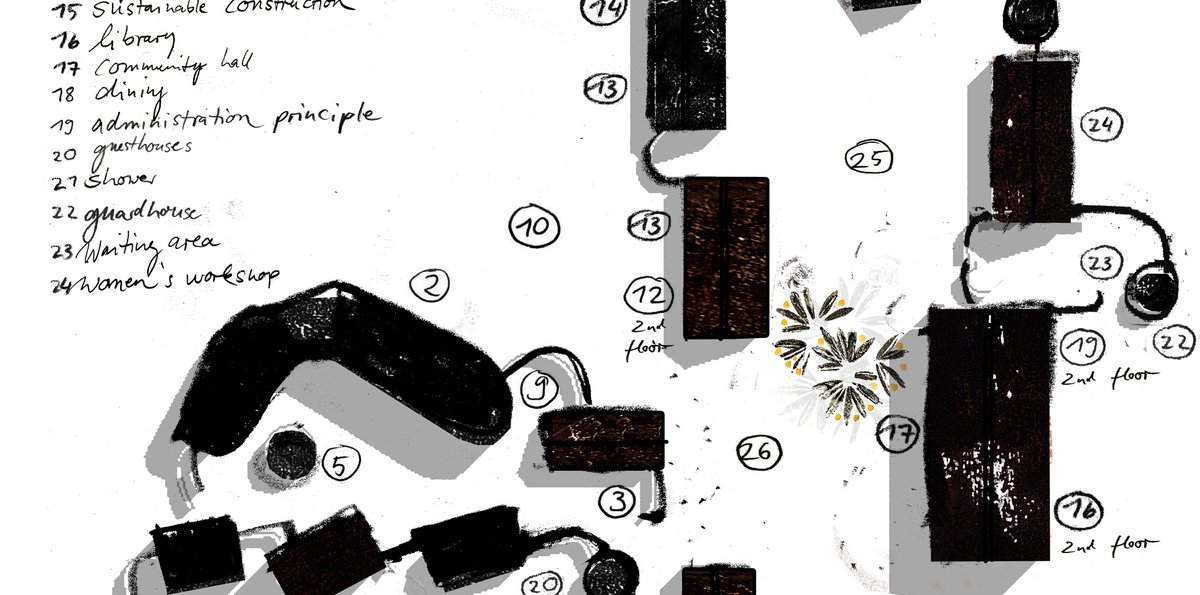

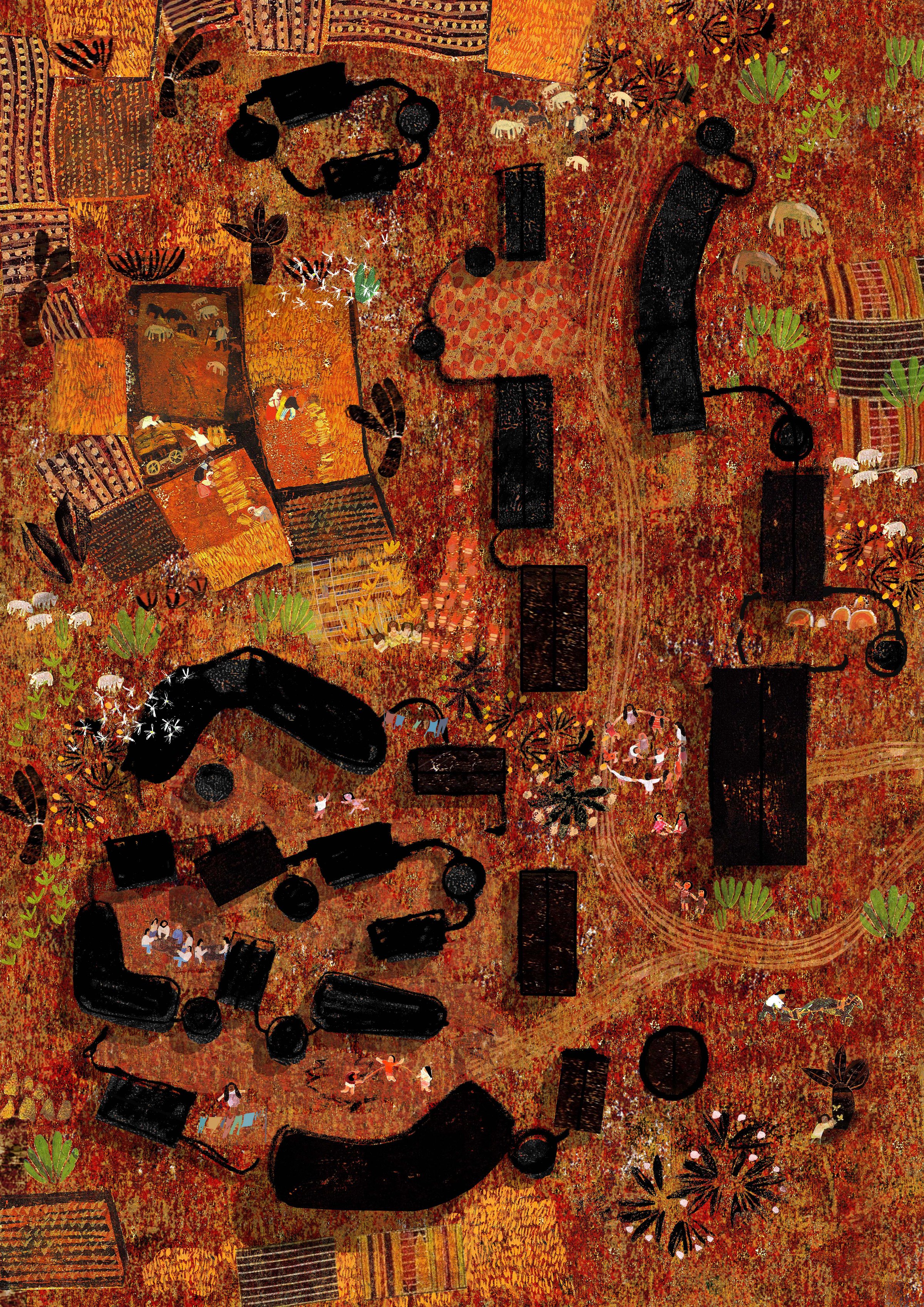

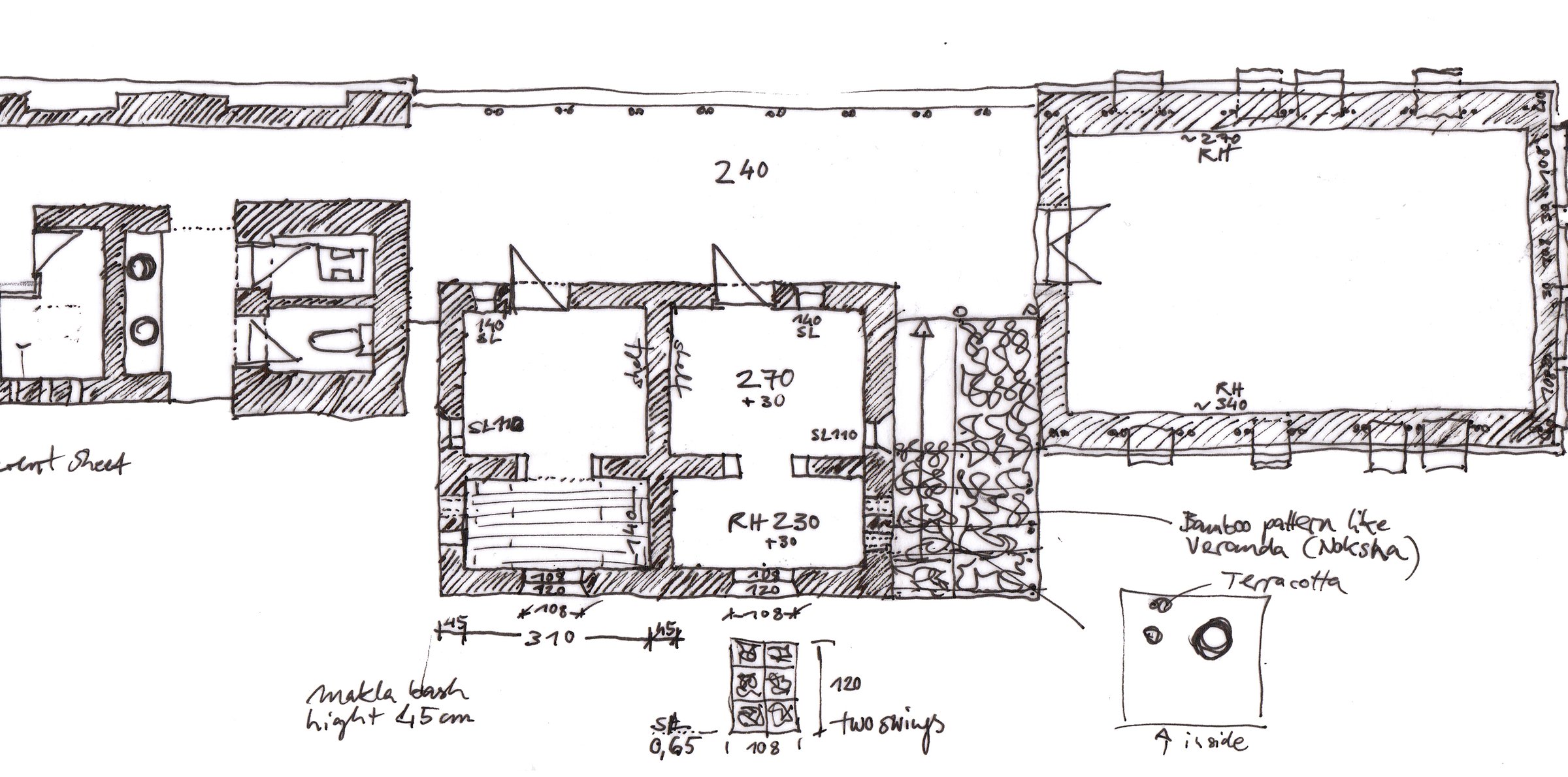

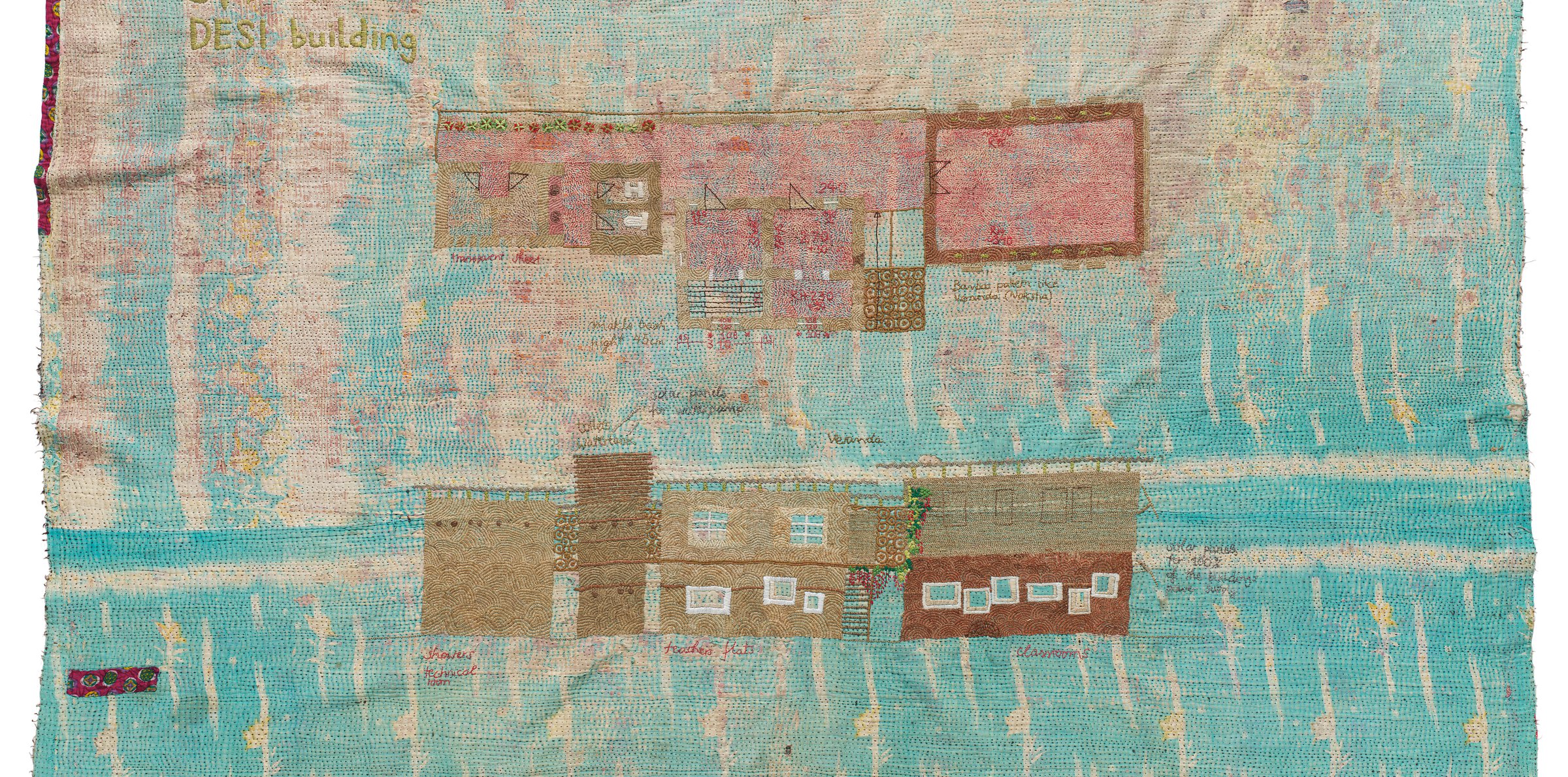

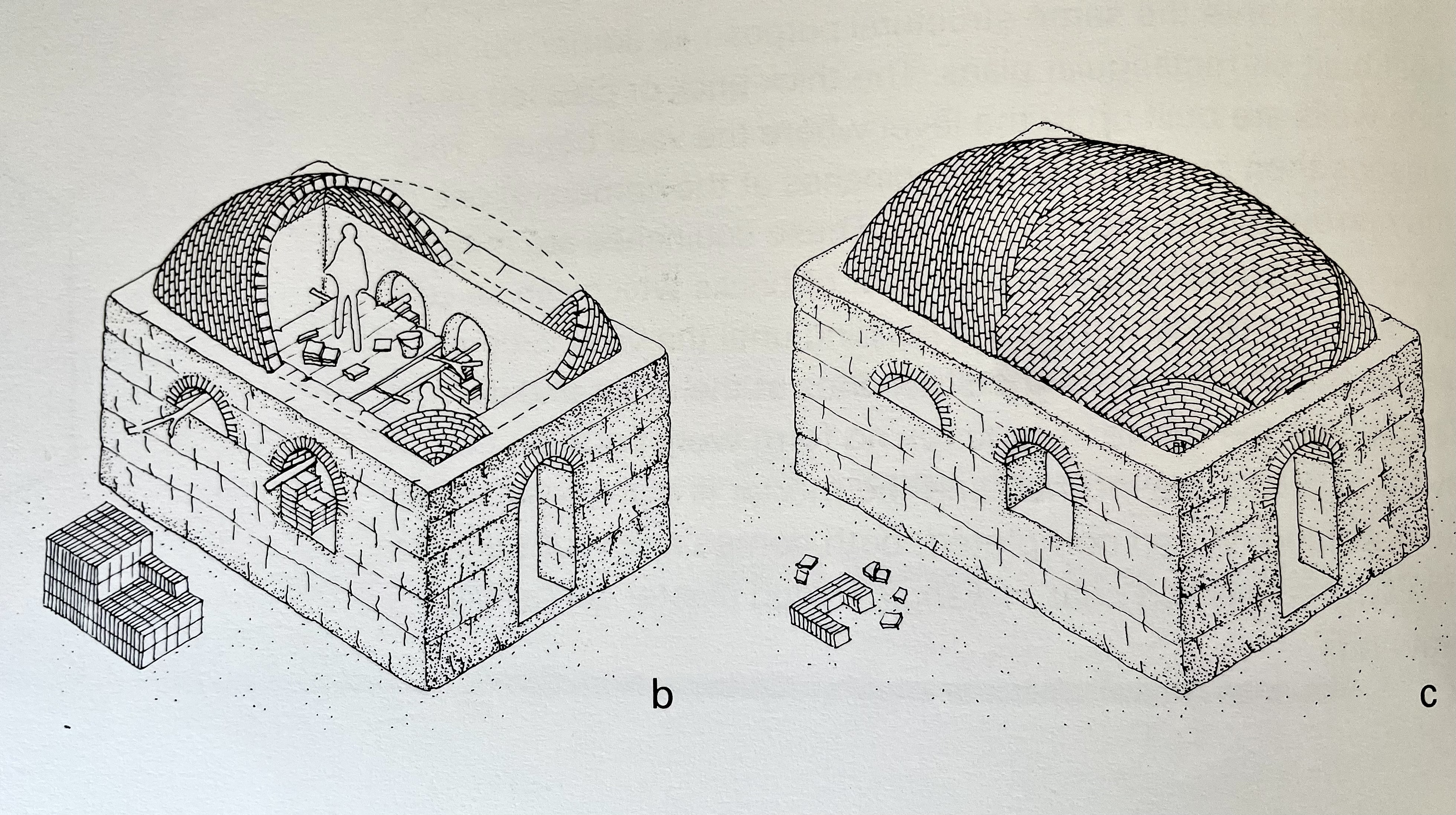

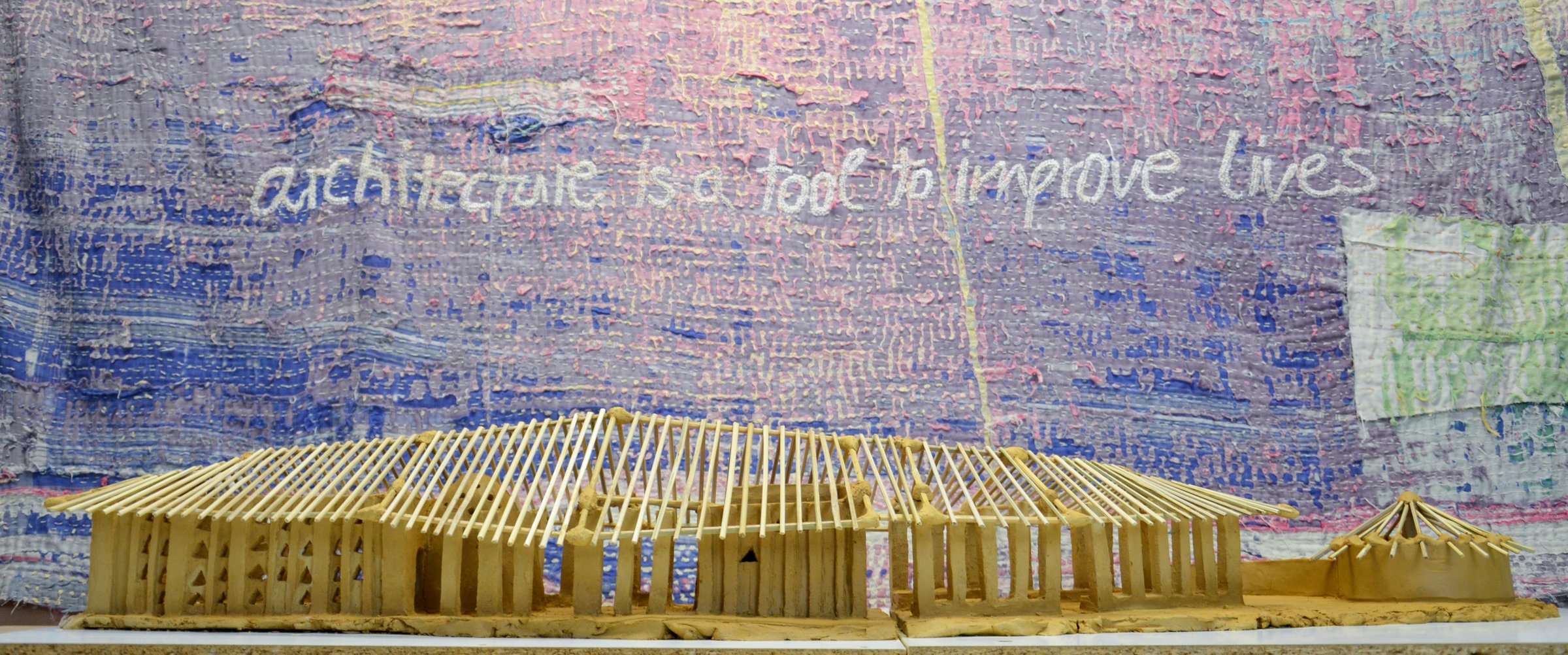

The Earth Campus in Tatale, Ghana, is a vocational training center designed to promote sustainable development through education and practical skill-building in one of Ghana’s rural regions, close to the Togo border. The project focuses on providing young people with the skills needed to support their families and counteract rural exodus. It is operated by the Salesians with the Don Bosco mission, which aims to empower the local community through sustainable techniques and education.

The Earth Campus in Tatale, Ghana, is a vocational training center designed to promote sustainable development through education and practical skill-building in one of Ghana’s rural regions, close to the Togo border. The project focuses on providing young people with the skills needed to support their families and counteract rural exodus. It is operated by the Salesians with the Don Bosco mission, which aims to empower the local community through sustainable techniques and education.