Name: Xiguan Lei 習關磊

Occupation: Sculptor, Painter, Poet.

Born: Dali, China, in 1994

Location: He now lives and works in Chongqing and Dali.

Xi’s art, which is always gentle – even to the point of being hard to discern, built as it often is from organic matter and placed amongst leaves, moss, stones, and bark – is also, in fact, making a very bold and visionary proposal.

Nature and Self

Xi’s proposal is this: that Self and Nature need not be separate entities. He is not expressing or documenting or representing either Self or Nature. Instead, he is exploring ways that Self and Nature relate and interpenetrate. He is actively demonstrating that one is part of the other. Thus, his interventions into Nature are a ‘working with’ Nature’s materials and a ‘working with’ Nature’s seasons and Nature’s cycles of time. If we see his naked body becoming part of the work, it is not to promote the ego of the artist, or to titillate – it is to make the far bolder assertion that we, as human beings, are part of Nature’s constant motion and materiality.

“The soil is part of us. We are part of the soil. The bamboo forest is part of us. We are part of the bamboo forest. We are as vulnerable as Nature, as porous, as interdependent, as constantly changing, as borderless.”

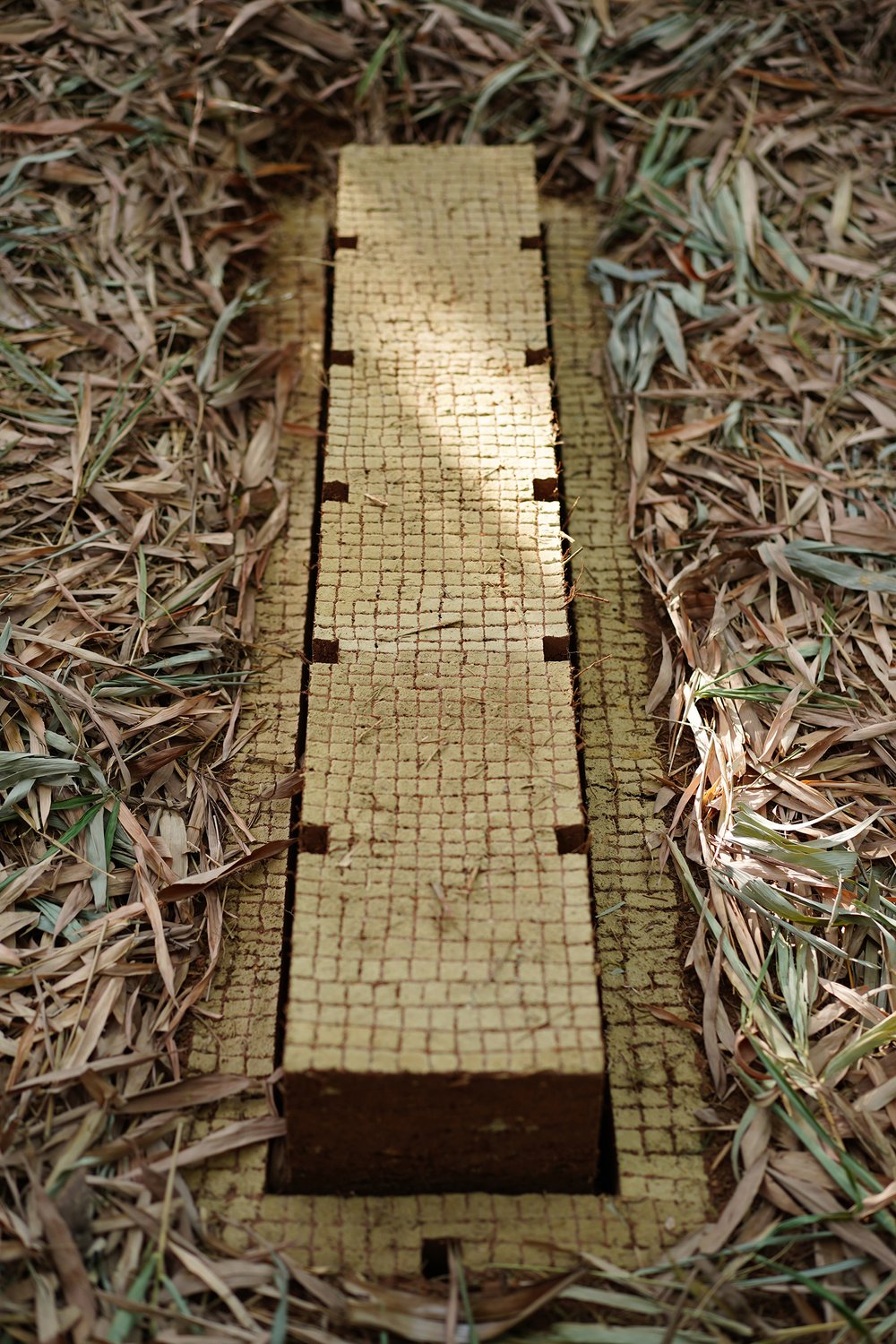

In his artistic practice rooted in human interventions into nature, the creator Xiguan Lei becomes a subtle orchestrator, leaving vanishing trails and marks that seamlessly blend with the natural landscape yet bear the unmistakable imprint of human hands. Reminiscent of land art pioneers like Richard Long or Robert Smithson, the artist engages in a poetic dialogue with the environment, crafting ephemeral installations that challenge the boundaries between the natural and the man-made.

Geometric Concepts

Xi’s methodology is influenced by Descartes’ and Spinoza’s geometric concepts including Rectangular Setup and Extension, Einstein’s theory of space, and the mathematical ideas of Euler and Gauss. He lays out the material in a particular shape, size, volume, and manner. We can see the sharp and hard edges and minimalism everywhere in the various forms of adobes and plants, with parts of the works independent of and also participating in the whole. Xi advocates that the viewer “walk through” the landscape and perceive the deep connection with nature. Put together, the images of their works both reveal the sense of mystery and miracle, where artistic phenomena are created and disappear in the rhythm of nature.

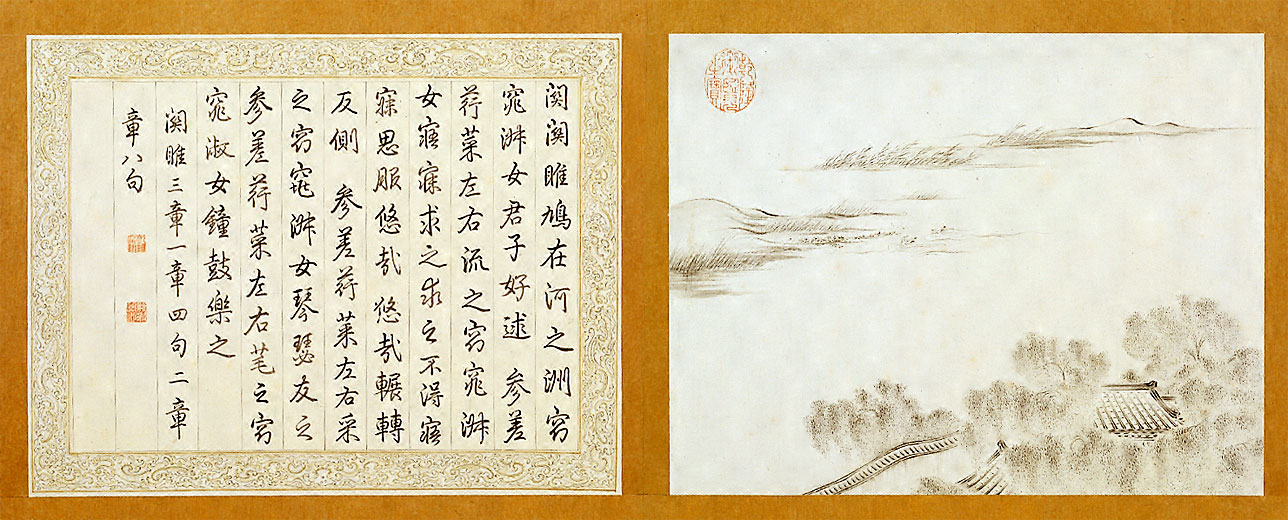

Classic of Poetry (Shijing)

Xi gathers material on the spot including soil and plants to create his works. Surrounded by mosses, ferns, and seed plants, the hand-made adobes are arranged solidly in a structural manner. This is the most iconic series of his works whose titles are quoted from classical Chinese literature: the Book of Songs and the Songs of Chu, such as It is Nice to be in the Garden, There is a Sandalwood (乐彼之园,爰有树檀) (2019), Swoop Flies that Falcon, Dense that Northern Wood (鴥彼晨风,郁彼北林) (2020), and The Appearance and Height of the Lush Plants Match Beautifully (纷緼宜修) (2020). Xi borrows these responses from ancient Chinese philosophers to the rhythms of nature, alluding to the unity of the abstract structure and figurative content in his works, and the fusion of classical Eastern aesthetics with Western spatial geometry. Legitimately, Xi calls his works “Land Art” rather than installations or sculptures. In terms of Land Art, it uses nature as the creative medium, and always emphasizes the visual form of the site-specific context, looking for an organic integration between the works and nature. One Issues from the Dark Valley and Removes to the Lofty Tree (出自幽谷,迁于乔木) (2019) , one of the series of adobes, created in 2019 and eroded back to the land during the rainy season in 2021, which is a vivid projection of the journey of human life.

Taoism and Anthropocene era

Lei’s work does not need – and probably not always meant – to be contained in a gallery or put against a wall because this would undermine his core artistic if not philosophical purpose: this is only in nature, out in the open air, where Lei’s adobes turn to be his art. This is out there that time can do his essential share, that is slowly absorbing as a sound graft Lei’s adobes as they are designed to be. Lei’s structures, given the infinite potential of adobes, can take all sort of forms: they can be seen as burial site or places of meditation – see “1120 Conversations I had with Moss and a Rock”, “I’m Walking in the Field”.

Once build or installed in nature, Lei’s structures slowly fade away, change form and aspect over time and may eventually disappear. This is a key point about Lei’s artworks: as they are made from earth, they are designed to evolve when placed on the ground, slowly and silently, and possibly completely disappear. This gives the opportunity for the observer to witness not a still artwork but an evolution, that is the exact opposite of a still life: real life. We cannot but notice the humility of Lei’s artistic approach. From a Chinese viewpoint, the reference to Taoism comes readily to the mind when trying to understand Lei’s artistic approach. Laozi Tao Te Ching, to put it in a few poor words, teaches us that all things come from a unique energy, transforms, fades away and recycle in the “logos”.

Xiguan Lei’s artistic practice holds a significant role within the contemporary environmental discourse framed by the Anthropocene. As we grapple with the profound impact of human activities on the planet, his installations and sculptures serve as poignant reflections and catalysts for conversations surrounding humanity’s relationship with the environment in this epoch. The ephemeral nature of his works mirrors the transience inherent in the Anthropocene era. The marks left by the artist’s body and other interventions evoke the impermanence of our impact on the environment, fostering a contemplation of the evolving and often precarious balance between human activity and the natural world.

Lei considers his art “a grand and silent game of building blocks”. He also told that those adobes could be considered words. That begs the question of their meaning. Just as the stones used in ancient civilization building, Lei’s adobes talk to anyone willing to listen. But the observer has to be tender ear because Lei’s art is elegant and subtle enough only to whisper. As to what it is whispering, “The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao”. This is how much Xiguan Lei’s art can offer: a glance at eternity.

References: