Based in Monterrey, Mexico, Diseño Norteño is an architecture firm celebrated for merging modern innovation with the cultural heritage of northern Mexico. Their projects are designed to respect the natural environment, utilizing local materials and reinterpreting traditional techniques with a contemporary twist. With a multidisciplinary team, they have become known for creating spaces that reflect regional identity while delivering functional and forward-thinking design solutions.

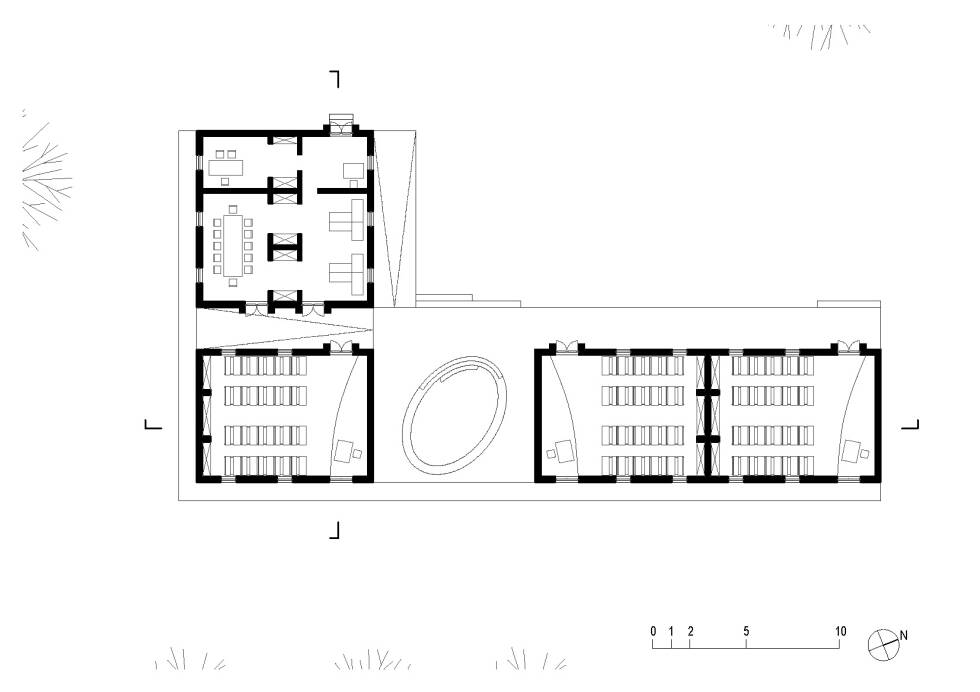

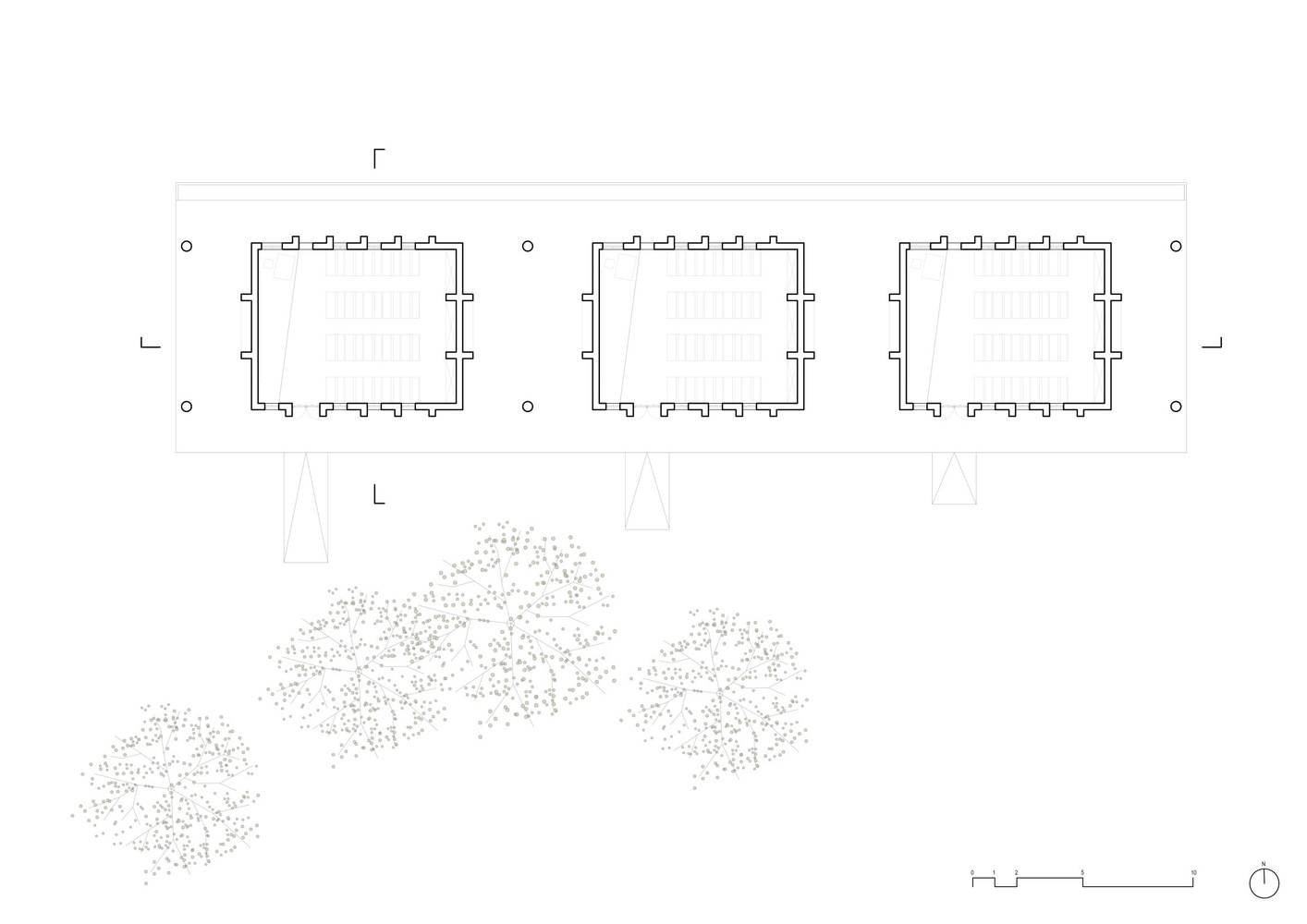

The “OJA” project, located in the serene landscapes of Coahuila, Mexico, showcases Diseño Norteño’s dedication to sustainability and elegant design. “OJA” serves as a harmonious retreat, blending seamlessly with its natural surroundings. The project draws inspiration from traditional northern Mexican architecture, adapted to a modern context, to create a sanctuary that respects and enhances its environment.

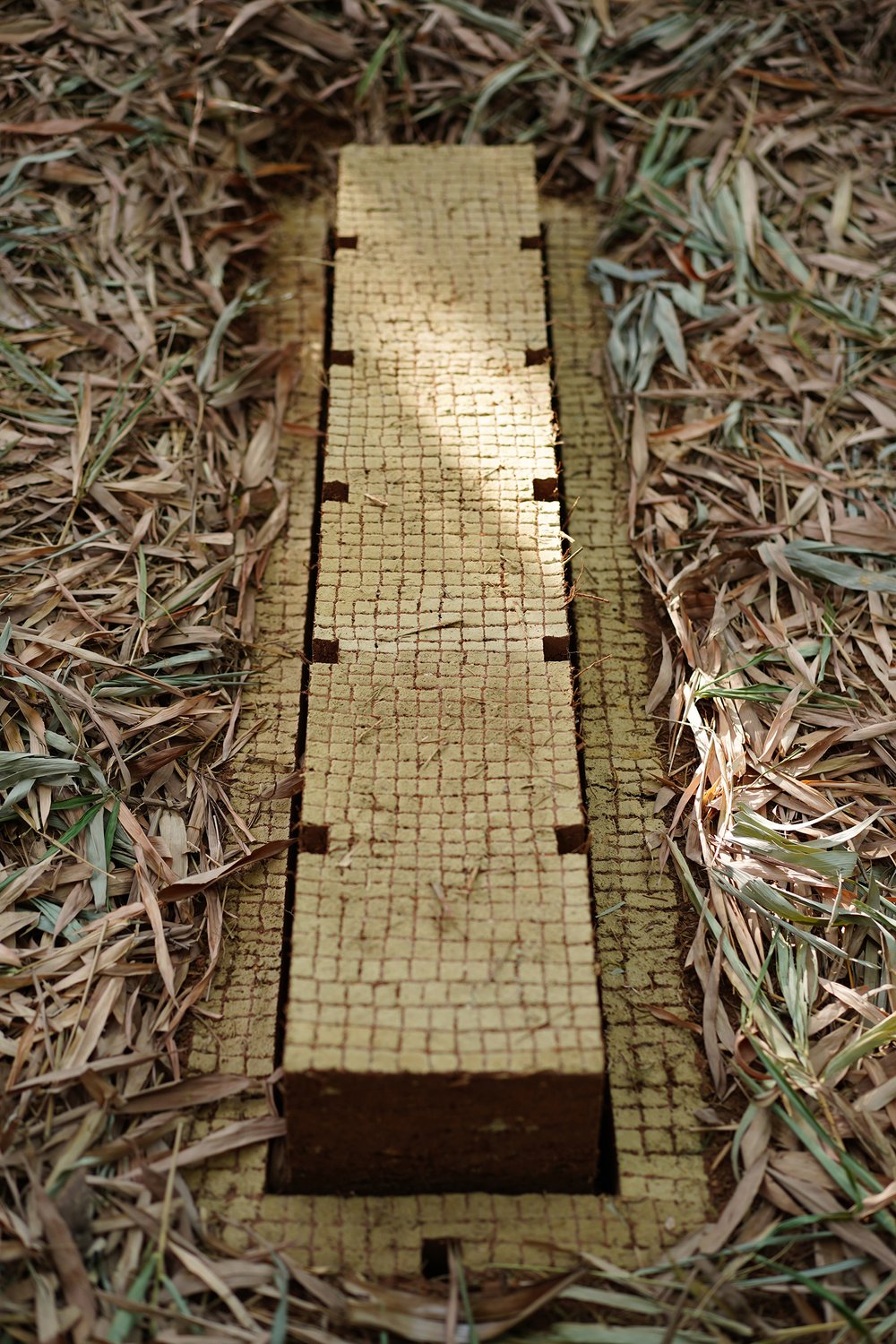

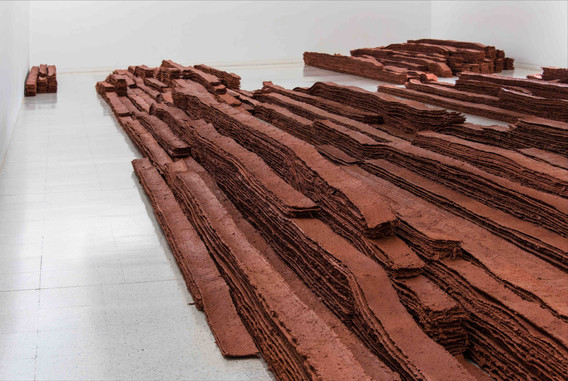

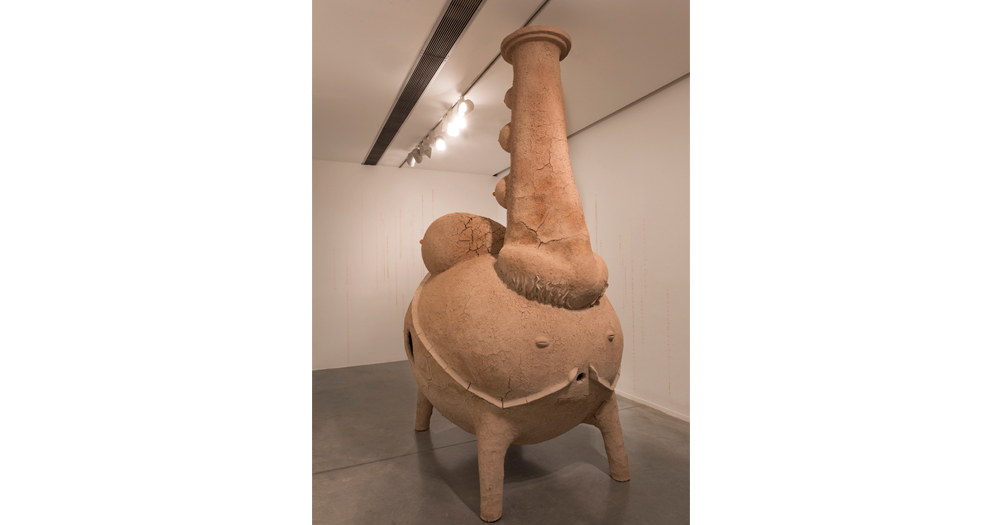

Key materials used in the “OJA” project include compressed earth, which is a contemporary twist on traditional earthen construction. This material not only provides excellent thermal insulation, keeping the indoor environment comfortable year-round, but also minimizes environmental impact by utilizing locally sourced resources. Recycled wood plays a significant role as well, adding warmth and a rustic charm to the interiors, creating inviting spaces that feel both cozy and grounded. Additionally, local stone is incorporated for its durability and aesthetic qualities, establishing a strong connection between the building and its natural surroundings. This thoughtful selection of materials enhances the visual appeal of the structure while reinforcing the project’s commitment to eco-friendliness and sustainability. By choosing materials that are both beautiful and environmentally responsible, “OJA” embodies a harmonious relationship between design and nature.

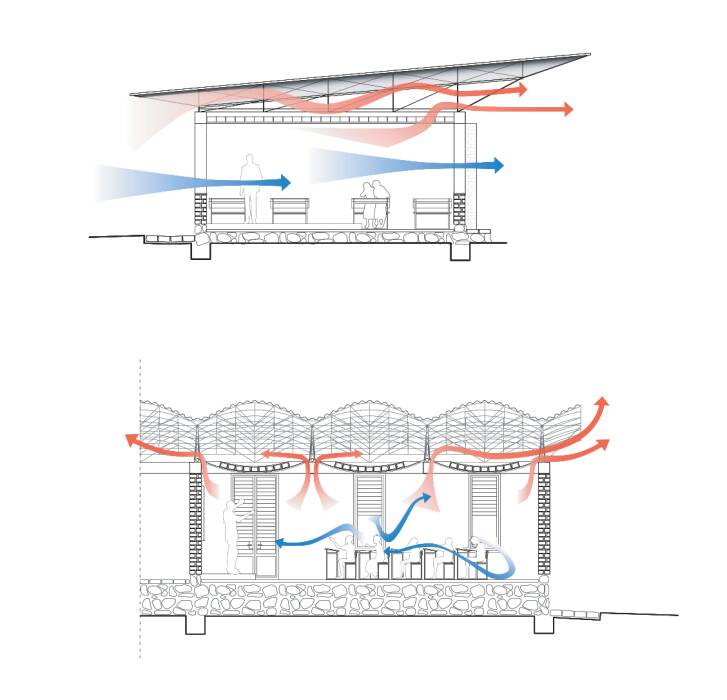

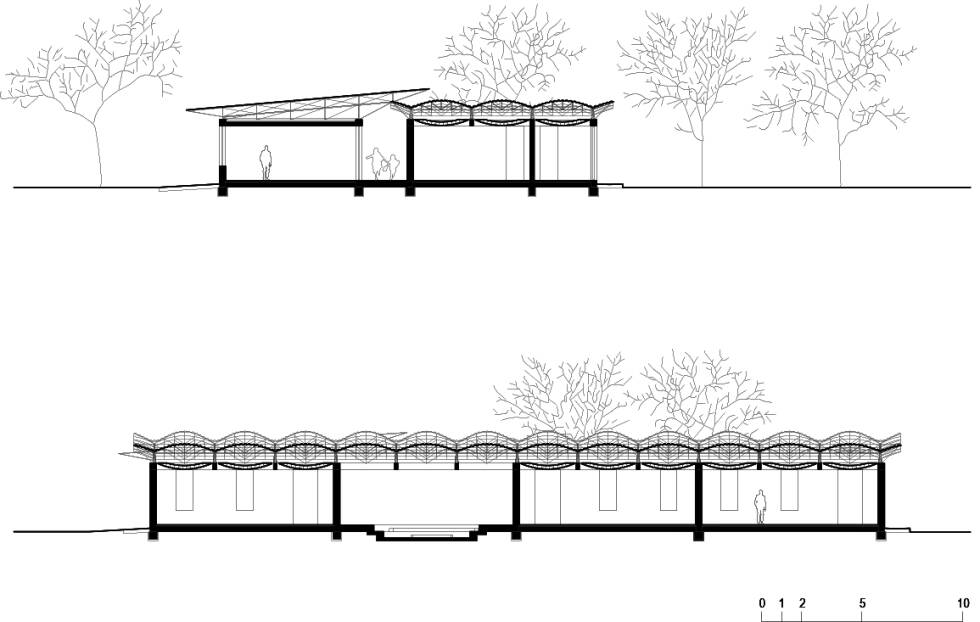

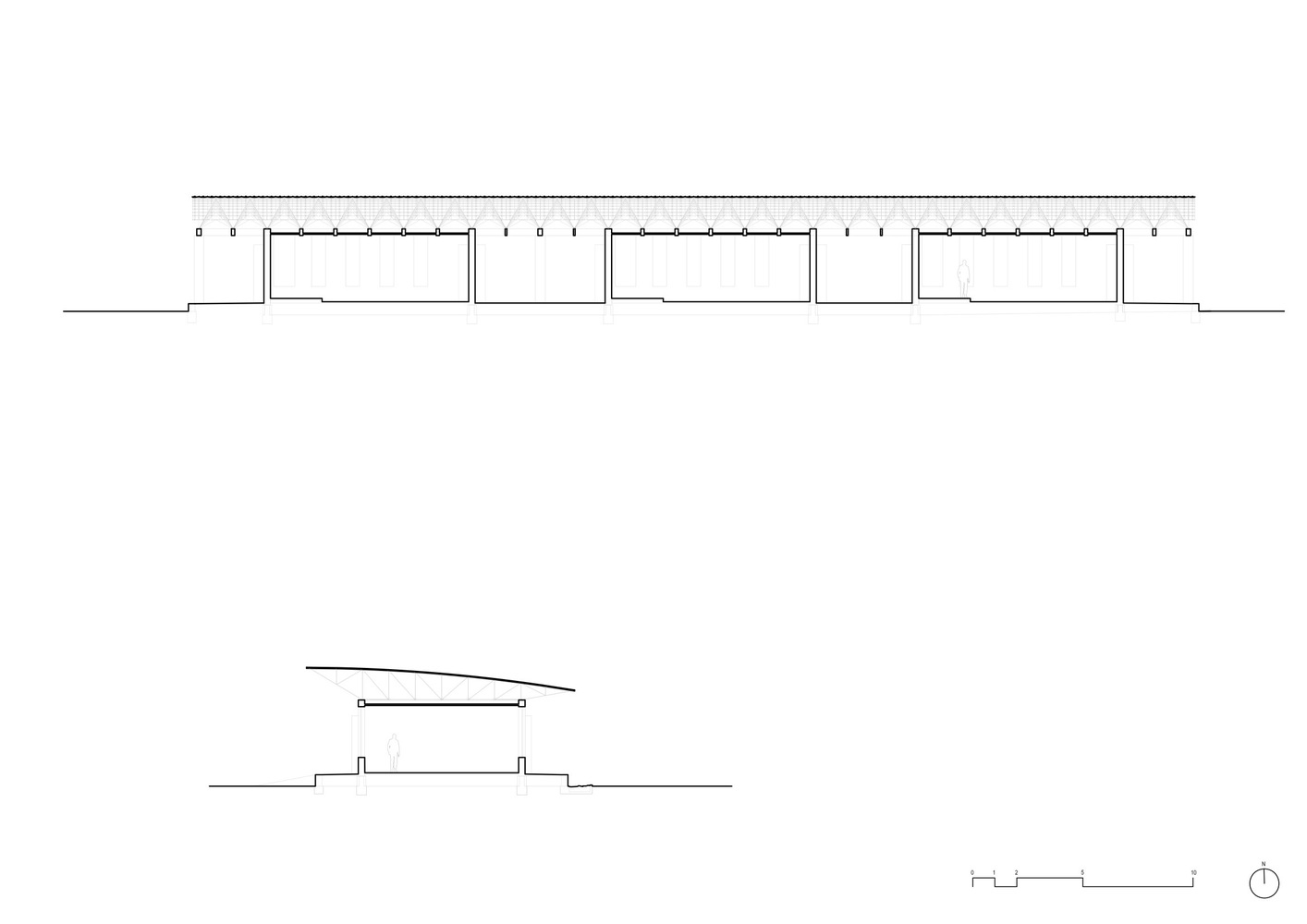

“OJA” employs several passive design techniques to improve sustainability. The building is oriented to maximize natural light and promote cross ventilation, reducing reliance on artificial heating and cooling. Large windows and strategic shading devices protect the interiors from excessive heat, while modern systems like rainwater harvesting and solar panels further enhance self-sufficiency. Together, these elements create a beautiful, functional space that reflects a harmonious blend of traditional practices and contemporary innovations, reinforcing the project’s commitment to ecological and cultural sustainability.

References

(n.d.). Diseño Norteño – Tijuana. Retrieved November 5, 2024, from https://d-n.mx/

Diseño Norteño. (@disenonorteno) • Instagram photos and videos. (n.d.). Instagram. Retrieved November 5, 2024, from https://www.instagram.com/disenonorteno/

Vega, R. P. (2023, August 22). La arquitectura más allá del centro de México. Mural. https://www.mural.com.mx/la-arquitectura-mas-alla-del-centro-de-mexico/ar2661626

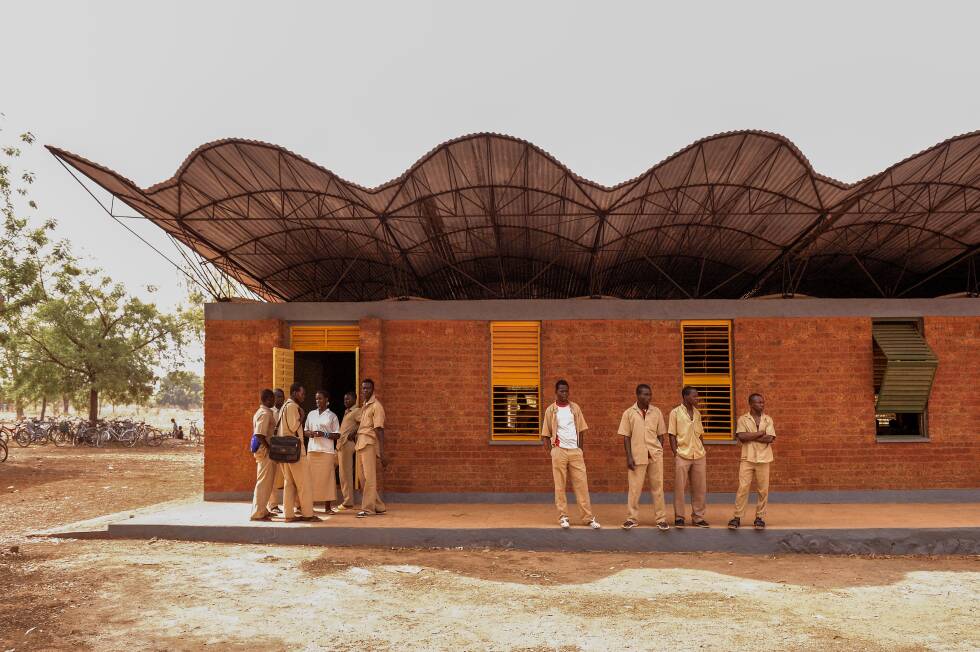

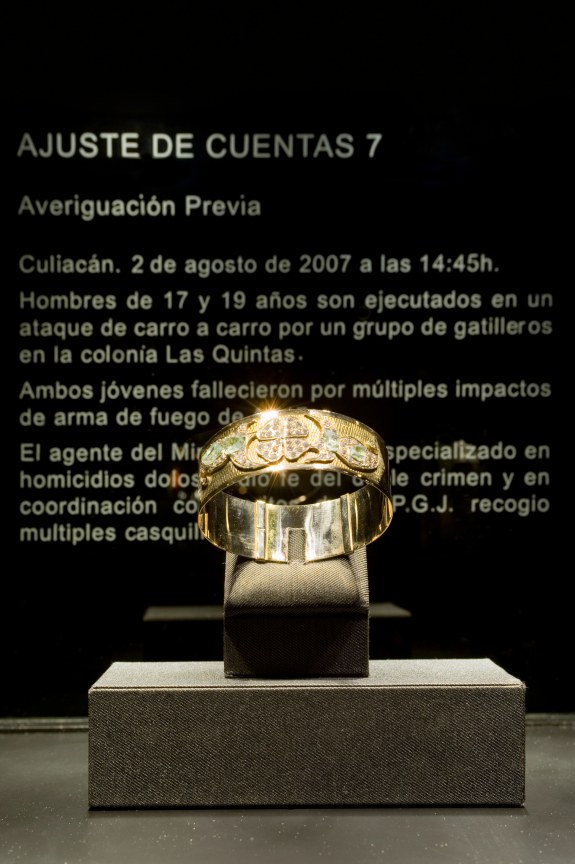

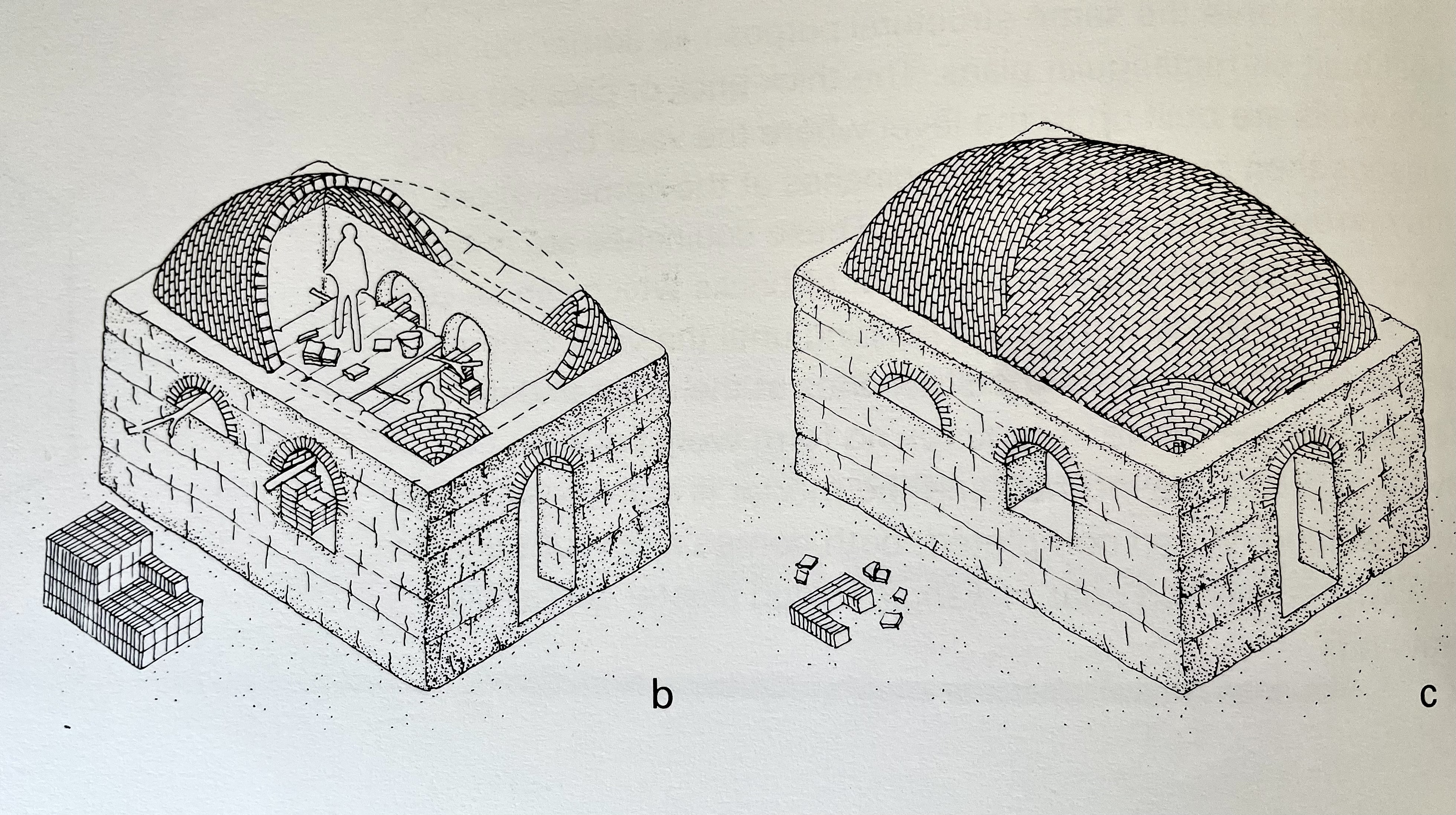

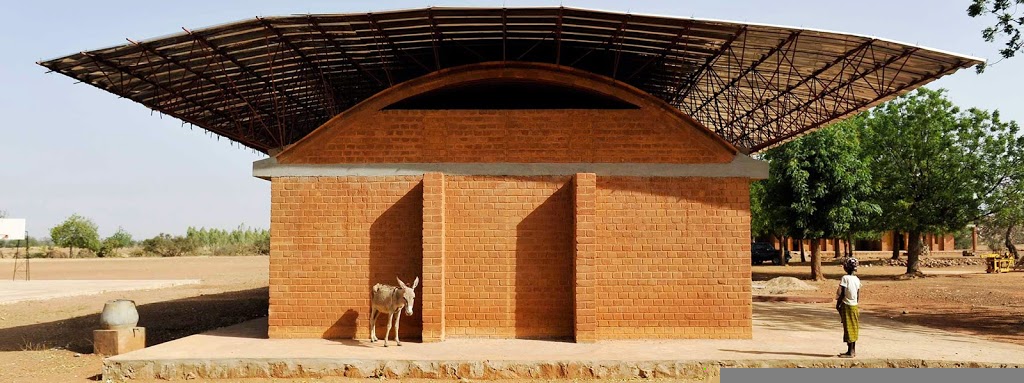

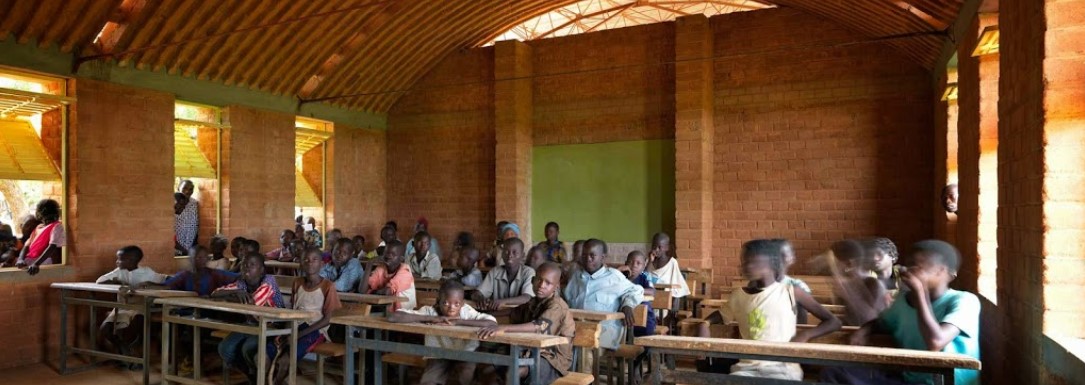

Interior of the vaulted ceiling classroom

Interior of the vaulted ceiling classroom